Reproductive System – Female

Published .

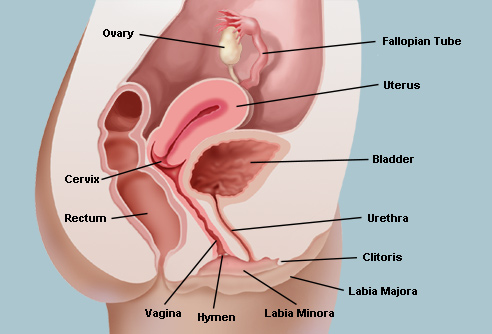

The organs of the female reproductive system produce and sustain the female sex cells (egg cells or ova), transport these cells to a site where they may be fertilized by sperm, provide a favorable environment for the developing fetus, move the fetus to the outside at the end of the development period, and produce the female sex hormones. The female reproductive system includes the ovaries, Fallopian tubes, uterus, vagina, accessory glands, and external genital organs.

- Ovaries

- Genital Tract

- External Genitalia

- Female Sexual Response and Hormonal Control

- Mammary Glands

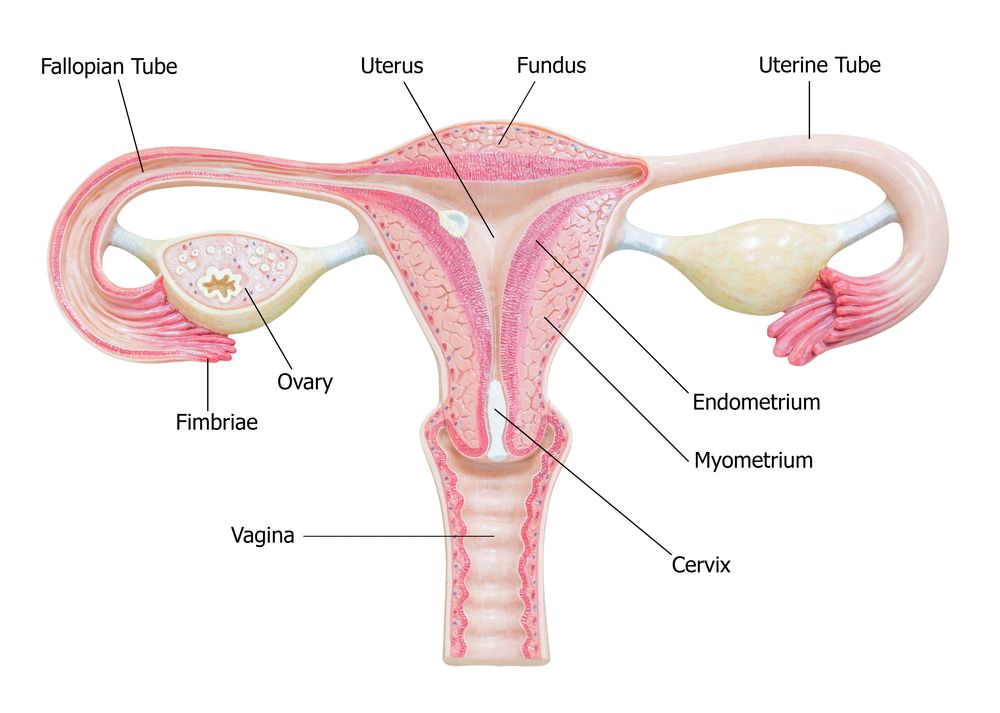

The primary female reproductive organs, or gonads, are the two ovaries. Each ovary is a solid, ovoid structure about the size and shape of an almond, about 3.5 cm in length, 2 cm wide, and 1 cm thick. The ovaries are located in shallow depressions, called ovarian fossae, one on each side of the uterus, in the lateral walls of the pelvic cavity. They are held loosely in place by peritoneal ligaments.

The ovaries are covered on the outside by a layer of simple cuboidal epithelium called germinal (ovarian) epithelium. This is actually the visceral peritoneum that envelops the ovaries. Underneath this layer is a dense connective tissue capsule, the tunica albuginea. The substance of the ovaries is distinctly divided into an outer cortex and an inner medulla. The cortex appears more dense and granular due to the presence of numerous ovarian follicles in various stages of development. Each of the follicles contains an oocyte, a female germ cell. The medulla is a loose connective tissue with abundant blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerve fibers.

Female sex cells, or gametes, develop in the ovaries by a form of meiosis called oogenesis. The sequence of events in oogenesis is similar to the sequence in spermatogenesis, but the timing and final result are different. Early in fetal development, primitive germ cells in the ovaries differentiate into oogonia. These divide rapidly to form thousands of cells, still called oogonia, which have a full complement of 46 (23 pairs) chromosomes. Oogonia then enter a growth phase, enlarge, and become primary oocytes. The diploid (46 chromosomes) primary oocytes replicate their DNA and begin the first meiotic division, but the process stops in prophase and the cells remain in this suspended state until puberty. Many of the primary oocytes degenerate before birth, but even with this decline, the two ovaries together contain approximately 700,000 oocytes at birth. This is the lifetime supply, and no more will develop. This is quite different than the male in which spermatogonia and primary spermatocytes continue to be produced throughout the reproductive lifetime. By puberty the number of primary oocytes has further declined to about 400,000.

Ovulation, prompted by luteinizing hormone from the anterior pituitary, occurs when the mature follicle at the surface of the ovary ruptures and releases the secondary oocyte into the peritoneal cavity. The ovulated secondary oocyte, ready for fertilization is still surrounded by the zona pellucida and a few layers of cells called the corona radiata. If it is not fertilized, the secondary oocyte degenerates in a couple of days. If a sperm passes through the corona radiata and zona pellucida and enters the cytoplasm of the secondary oocyte, the second meiotic division resumes to form a polar body and a mature ovum

There are two uterine tubes, also called Fallopian tubes or oviducts. There is one tube associated with each ovary. The end of the tube near the ovary expands to form a funnel-shaped infundibulum, which is surrounded by fingerlike extensions called fimbriae. Because there is no direct connection between the infundibulum and the ovary, the oocyte enters the peritoneal cavity before it enters the Fallopian tube. At the time of ovulation, the fimbriae increase their activity and create currents in the peritoneal fluid that help propel the oocyte into the Fallopian tube. Once inside the Fallopian tube, the oocyte is moved along by the rhythmic beating of cilia on the epithelial lining and by peristaltic action of the smooth muscle in the wall of the tube. The journey through the Fallopian tube takes about 7 days. Because the oocyte is fertile for only 24 to 48 hours, fertilization usually occurs in the Fallopian tube.

The uterus is a muscular organ that receives the fertilized oocyte and provides an appropriate environment for the developing fetus. Before the first pregnancy, the uterus is about the size and shape of a pear, with the narrow portion directed inferiorly. After childbirth, the uterus is usually larger, then regresses after menopause. The uterus is lined with the endometrium. The stratum functionale of the endometrium sloughs off during menstruation. The deeper stratum basale provides the foundation for rebuilding the stratum functionale.

The vagina is a fibromuscular tube, about 10 cm long, that extends from the cervix of the uterus to the outside. It is located between the rectum and the urinary bladder. Because the vagina is tilted posteriorly as it ascends and the cervix is tilted anteriorly, the cervix projects into the vagina at nearly a right angle. The vagina serves as a passageway for menstrual flow, receives the erect penis during intercourse, and is the birth canal during childbirth.

The external genitalia are the accessory structures of the female reproductive system that are external to the vagina. They are also referred to as the vulva or pudendum. The external genitalia include the labia majora, mons pubis, labia minora, clitoris, and glands within the vestibule.

Follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, estrogen, and progesterone have major roles in regulating the functions of the female reproductive system.

Menopause occurs when a woman’s reproductive cycles stop. This period is marked by decreased levels of ovarian hormones and increased levels of pituitary follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone. The changing hormone levels are responsible for the symptoms associated with menopause.

Functionally, the mammary glands produce milk; structurally, they are modified sweat glands. Mammary glands, which are located in the breast overlying the pectoralis major muscles, are present in both sexes, but usually are functional only in the female.

Externally, each breast has a raised nipple, which is surrounded by a circular pigmented area called the areola. The nipples are sensitive to touch, due to the fact that they contain smooth muscle that contracts and causes them to become erect in response to stimulation.

Internally, the adult female breast contains 15 to 20 lobes of glandular tissue that radiate around the nipple. The lobes are separated by connective tissue and adipose. The connective tissue helps support the breast. Some bands of connective tissue, called suspensory (Cooper’s) ligaments, extend through the breast from the skin to the underlying muscles. The amount and distribution of the adipose tissue determines the size and shape of the breast. Each lobe consists of lobules that contain the glandular units. A lactiferous duct collects the milk from the lobules within each lobe and carries it to the nipple. Just before the nipple, the lactiferous duct enlarges to form a lactiferous sinus (ampulla), which serves as a reservoir for milk. After the sinus, the duct again narrows and each duct opens independently on the surface of the nipple.

Mammary gland function is regulated by hormones. At puberty, increasing levels of estrogen stimulate the development of glandular tissue in the female breast. Estrogen also causes the breast to increase in size through the accumulation of adipose tissue. Progesterone stimulates the development of the duct system. During pregnancy, these hormones enhance further development of the mammary glands. Prolactin from the anterior pituitary stimulates the production of milk within the glandular tissue, and oxytocin causes the ejection of milk from the glands.