The Autonomic Nervous System

Published (updated: ).

The brain has better things to do than worry about contracting the smooth muscle of the large intestine just in time for that 9 am bowel movement. The brain has better things to do than worry about how fast the metabolism is working. The brain has better things to do than worry about exactly what part of a Fallopian tube has the egg in it. What is a brain to do? Delegate, of course. The brain delegates many of the daily or automatic functions the body has to do the autonomic nervous system. The brain still needs to be in control of everything, but creating a network of nerves for every little thing would add an unnecessary complication.

The autonomic nervous system is a visceral efferent system, which means it sends motor impulses to the visceral organs. It functions automatically and continuously, without conscious effort, to innervate smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, and glands. It is concerned with heart rate, breathing rate, blood pressure, body temperature, and other visceral activities that work together to maintain homeostasis.

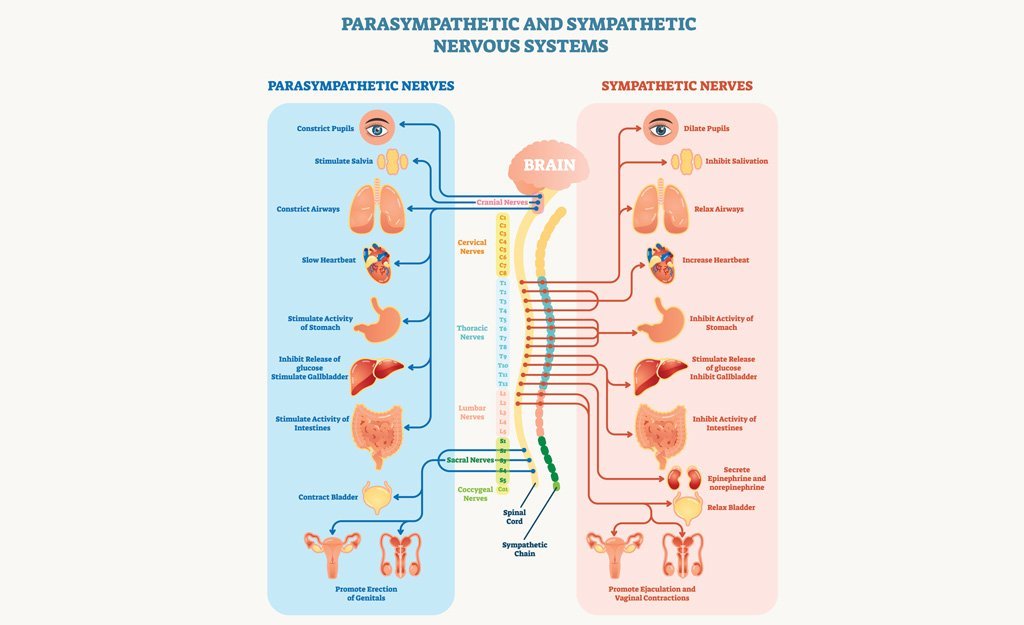

The autonomic nervous system has two parts, the sympathetic division and the parasympathetic division. Many visceral organs are supplied with fibers from both divisions. In this case, one stimulates and the other inhibits. This antagonistic functional relationship serves as a balance to help maintain homeostasis.

Right Now Problems

The sympathetic nervous system makes up part of the autonomic nervous system, also known as the involuntary nervous system. Without conscious direction, the autonomic nervous system regulates important bodily functions such as heart rate, blood pressure, pupil dilation, body temperature, sweating and digestion. The system allows animals to make quick internal adjustments and react without having to think about it.

The sympathetic nervous system directs the body’s rapid involuntary response to dangerous or stressful situations. A flash flood of hormones boosts the body’s alertness and heart rate, sending extra blood to the muscles. Breathing quickens, delivering fresh oxygen to the brain, and an infusion of glucose is shot into the bloodstream for a quick energy boost. This response occurs so quickly that people often don’t realize it’s taken place, for instance, a person may jump from the path of a falling tree before they fully register that it’s toppling toward them.

The control of heart rate and blood flow is essential even for mundane tasks such as standing up. People who suffer from orthostatic intolerance (OI) can experience chronic lightheartedness and fainting from the simple act of getting into an upright posture, called orthostasis. The autonomic nervous system controls the necessary changes to the vasculature and heart rate when we engage in orthostasis. In particular, the parasympathetic system is responsible for the signals that allow vasodilation—the relaxing of the muscles around lining the blood vessels—of the cerebral arteries. Improper signaling by the parasympathetic nervous system can cause loss of consciousness due to inadequate blood flow to the brain.

24 Hour Problems

Activation of the parasympathetic system tends to have a relaxing effect on the body, promoting functions that replenish resources and restore homeostasis. It is therefore sometimes referred to as the “rest and digest” system. The parasympathetic system predominates during calm times when it is safe to devote resources to basic “housekeeping” functions without a threat of attack or harm.

The parasympathetic nervous system can be activated by various parts of the brain, including the hypothalamus. Preganglionic neurons in the brainstem and sacral part of the spinal cord first send their axons out to ganglia—clusters of neuronal cell bodies—in the peripheral nervous system. These ganglia contain the connections between pre- and postganglionic neurons and are located near the organs or glands that they control. From here, postganglionic neurons send their axons onto target tissues—generally smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, or glands. Typically, the neurotransmitter acetylcholine is used to regulate the activity of these targets.

Activation of the parasympathetic system causes a variety of effects on the body. It lowers heart rate and causes the pupils to constrict—restoring the body to a more relaxed state. It also stimulates digestion and excretion—for instance, by promoting salivation, peristaltic contractions in the stomach and intestines, and contraction of the bladder to expel urine. It helps rebuild energy stores by causing the pancreas to secrete more insulin. Finally, it even promotes reproduction by increasing blood flow to the genitals.