Delivering The Baby

Published (updated: ).

Personnel

For a normally anticipated vaginal delivery, a physician or a midwife with the aide of a nurse can appropriately and safely perform the procedure. Additional personnel are optional, however additional support and coaching from a formally trained doula, family member, and/or partner can enhance the experience for the mother and results in a decreased need for analgesia. In addition, a pediatrician and an anesthesiologist should be available and on-call for any complications related to vaginal delivery.

Preparation

As with any procedure, appropriate preparation and positioning of the patient are key to maximizing the success of the procedure while simultaneously minimizing morbidity and mortality. There are many factors to consider in preparing a patient for a vaginal delivery and the position of the patient changes based on the progression of labor through its various stages.

Patients should be adequately hydrated, as hypovolemia during labor can cause fetal heart tracing abnormalities. Routine administration of antacids, routine enemas, and perineal shaving is not indicated. Systemic antibiotics are indicated for a known positive Group B streptococcus (GBS) culture or unknown maternal GBS status. There is no evidence in the literature supporting intrapartum chlorhexidine to prevent maternal or neonatal infections during vaginal delivery; conversely, this can lead to vaginal irritation and discomfort. However, some institutions and providers routinely use povidone-iodine solutions, especially if there is intrapartum defecation during labor and delivery.

Once the patient is prepared for the delivery, it is important to ensure proper positioning for the vaginal delivery. For the first stage of labor, the patient should be connected to monitors to assess fetal and maternal vital signs, as well as maternal uterine contractions. Progression of labor can be assessed by regular pelvic exams to assess for cervical effacement and dilation; this examination can be done every three or four hours, or as needed. A Foley urinary catheter can be placed; however, it is not necessary. Current literature suggests that bladder distension does not affect labor progress. During the first stage of labor, mothers are encouraged to ambulate and move around on the bed until a comfortable position is reached. Walking during the first stage of labor has no effect on the progress of and does not cause inhibition of normal labor.

Pushing with contractions should begin and be encouraged once the cervix has completely dilated. At the time, the birthing bed should be detached with the physician by the patient’s vagina. The patient is encouraged to be in a position that is most comfortable for her while pushing, but it is generally a lying position where the patient is supine lithotomy position.

Once the fetus is delivered, during the third stage of labor, optimally, the fetus is placed on the mother’s chest with the umbilical cord initially clamped then cut, while the mother continues to maintain the same position until the placenta is delivered. After the placenta is delivered and all equipment is cleared, the mother can lay supine and recumbent in a position she finds most comfortable.

Technique

Once maximal cervical dilation is reached and the patient experiences regular contractions every two to three minutes, she should be encouraged to push. The best way to push is bearing down, and the patient can be coached by asking the patient to push for at least ten seconds and for at least two or three times per contraction. The patient should be encouraged to push towards the baby’s head, and can also be encouraged by asking the patient to minimize yelling while maximizing pushing.

While the patient continues to push, warm compresses can be applied, and the perineum can be massaged digitally with lubricant to soften and stretch the perineum. In women without a history of vaginal birth, perineal massage reduced the incidence of perineal trauma and the need for episiotomies but did not reduce the incidence of perineal trauma of any degree. The second stage of labor can continue as long as needed as long as fetal heart rate tracing is normal, and progress is achieved, which can be quantified by progression in the fetal station. Once the fetus reaches crowning, the delivery of the fetus is imminent. At this time, the head of the fetus exerts dilatory pressure on the perineum, which leads to a tremendous urge for mothers to push, but appropriate steps of delivery should be followed in order to minimize perineal trauma.

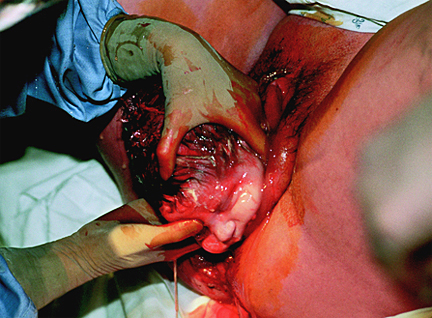

Once the head crowns, a sterile towel or lap pad can be used to hold the fetal head; one hand should support the fetal head and maintain it in the flexion position while the other hand should be used to support the lower edge of the perineum by pinching it to avoid tearing or trauma. During this time, the mother should be encouraged to stop pushing, and then use small contractions to enable the physician to control the pace of the fetal head delivery; precipitous delivery of the head can cause perineal trauma. Once the head is delivered, the mother should once again be asked to stop pushing, and the neck should be manually examined for the umbilical cord. If a nuchal cord is detected, it should be reduced, and then the delivery of the rest of the fetus should continue.

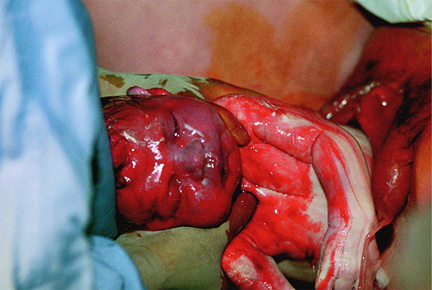

Routine oropharyngeal care through suctioning is no longer supported by evidence as gently wiping mucus from the child’s face and nose is found to be equivalent. Once the head is delivered, the next step is for delivery of the shoulders. With the next contraction, and using gentle downward traction towards the mother’s sacrum, the anterior shoulder is delivered as each side of the head is held. This maneuver allows the anterior shoulder to pass under the maternal pubic symphysis. While continuing to hold each side of the head, the posterior shoulder is delivered by applying gentle upward traction. It is important to apply the least amount of traction during the delivery of fetal shoulders to minimize the risk of traction-induced perineal injury and fetal brachial plexus injuries. After the shoulders are delivered, care must be maintained as the rest of the delivery is spontaneous and requires minimal maternal effort, but it is important to guide the newborn child’s body as it passes the birth canal. Once the child is delivered, the umbilical cord should be clamped after a delay. In full-term vaginal deliveries, evidence supports that delayed cord clamping, which is defined as clamping of the cord after 30 seconds, prevents anemia in infants. The umbilical cord should be clamped using two clamps that are approximately three to four centimeters apart. The partner of the mother or the accompanying family member should be afforded the opportunity to cut the umbilical cord between the two clamps. Once the cord is cut, the newborn should be cleaned, and one-minute and five-minute APGAR scores should be evaluated. If the APGAR scores are within normal limits, the infant should immediately be transferred to the mother and placed on her bare chest. Early Skin-to-skin contact between the newborn infant and mother serves a multitude of functions. It has been shown to increase mother-infant bond and attachment, improve breastfeeding outcomes, and minimize infant head loss.

The third stage of labor is defined as the time from the delivery of the fetus until the delivery of the placenta. Active management at this time of delivery can reduce the risk of severe postpartum hemorrhage and the need for blood transfusion. The active management of the third stage begins before the delivery of the placenta and includes uterotonic agent administration, application of gentle traction to umbilical cord after clamping it, and uterine massage. The preferred uterotonic agent is oxytocin, which is administered immediately after the delivery of the fetus. Signs of placental separation from the uterus, such as a gush of blood, should be observed as the uterus contracts. Cord traction facilitates the separation of the placenta and enables its delivery. One method of cord traction application is known as the Brandt-Andrews maneuver, in which one hand secures the uterine fundus on the abdomen to prevent uterine inversion while the other hand exerts sustained downward gentle traction of the clamp on the umbilical cord. This maneuver leads to a reduction in the need for manual placental removal; in addition, there is a statistically significant reduction in the duration of the third stage of labor, blood loss, and incidence of postpartum hemorrhage. Once the placenta is delivered, it should be thoroughly inspected on the outside and by inverting it to check for missing pieces, because retained products of conception are a known risk factor for postpartum hemorrhage.

Complications

There are numerous complications associated with vaginal delivery; these complications vary by stages of labor and are dependent on numerous factors. In general, complications can be generalized into the following categories: failure to progress, abnormal fetal heart rate tracing, intrapartum hemorrhage, and post-partum hemorrhage.

Failure to progress can happen in either the first stage or the second stage. Failure to progress in the first stage of labor can be either protraction of active phase of labor, which is defined as cervical dilation rate less than one to two centimeters per hour in women who’s cervix is at least six centimeters dilated. The arrest of the first stage of labor is defined as no change in cervical dilation for more than four hours in a woman with adequate uterine contraction strength (defined as 200 Montevideo units or greater) or no change in cervical dilation in a woman for more than six hours with inadequate contraction strength. Protracted labor can be managed by augmenting labor with oxytocin, which is a uterotonic agent. Women with arrested labor are managed by conversion of vaginal delivery to a cesarean section mode of delivery.

Failure to progress during the second stage of labor is diagnosed when there is minimal descent of the fetus in nulliparous women who have pushed for a minimum of three hours and multiparous women who have pushed for a minimum of two hours; women with epidural anesthesia are allowed slightly longer durations for pushing. Failure to progress during the second stage of labor due to inadequate contractions or minimal descent of the fetus can be managed by the administration of oxytocin to augment labor after 60-90 minutes of pushing. If this does not help, an operative vaginal delivery using a vacuum or forceps or a cesarean section should be considered.

Failure to progress can also be due to abnormal passage of descent for the fetus, which is directly related to cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD). CPD can be related to fetal malposition or macrosomia and is a subjective diagnosis which requires conversion of the delivery to a cesarean section. CPD is most commonly observed during the second stage of labor.

During a vaginal delivery, the fetal heart rate must be monitored, and decelerations during labor, whether early decelerations or late decelerations, can indicate head compression of the fetus, cord compression of the fetus, hypoxemia, and even anemia of the fetus. If an abnormal fetal heart rate persists, resolution can be attempted by removing labor augmenting agents such as oxytocin or repositioning the mother on the left lateral side. If these maneuvers do not lead to the resolution of the abnormal fetal heart rate, an emergent cesarean section is indicated.

Vaginal delivery can be complicated by intrapartum hemorrhage. During a normal vaginal delivery, some blood from the effacement of the cervix or minor trauma of the vaginal canal can mix with amniotic fluid and can present as a serosanguineous appearance. However, the presence of frank blood is abnormal and can either be due to placental abruption, uterine rupture, placenta accrete, undiagnosed placenta previa, or vasa previa. These conditions are true obstetric emergencies and require an emergent cesarean section.

Finally, vaginal deliveries can be complicated by postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). PPH can be due to atony of the uterus, trauma to the birth canal, retained products of conception or due to a coagulopathy; uterine atony is the most common cause of PPH.

Clinical Significance

Proper preparation, monitoring, and technique during vaginal delivery are important to minimize morbidity and mortality to both the mother and the fetus While cesarean section deliveries are absolutely necessary for certain peripartum conditions, cesarean section deliveries have been shown to increase the long-term risk of small bowel obstruction in women.

Additionally, cesarean sections correlate with an increased risk of uterine rupture, abnormal placentation for future pregnancies, ectopic pregnancies, preterm births, and stillbirth. Evidence suggests cesarean section deliveries lead to differing and altered physiology in neonates due to exposure to differing hormonal, physical, microbiological, and medical exposures, which can affect short-term and long-term development. Short-term risks to babies include alteration in the immune system, increased likelihood in developments of allergies, asthma, and reduced intestinal microbiome, while long-term risks include the development of obesity and risks associated with obesity.

Conversely, advantages of a successful vaginal delivery are numerous to both the baby and the mother. With a vaginal delivery, there is a higher chance of being able to breastfeed successfully shortly after delivery, decreased hospital stay after childbirth, rapid recovery physically and psychologically, and increased mother-child bond and attachment. For the baby, the benefits of vaginal delivery include improved hormonal and endocrinological functions such as blood sugar regulation, respiratory function, temperature regulation, and an increase in exploratory behaviors. Other benefits include better long-term growth, immunity, and development compared to children born as a result of a cesarean section.