Pediatric Pneumonia

Published (updated: ).

Globally, pneumonia is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children younger than the age of 5 years. Although the majority of deaths attributed to pneumonia in children are mostly in the developing world, the burden of disease is substantial, and there are significant healthcare-associated costs related to pneumonia in the developed world.

Etiology

The etiology of pneumonia in the pediatric population can be classified by age-specific versus pathogen-specific organisms. Neonates are at risk for bacterial pathogens present in the birth canal, and this includes organisms such as group B streptococci, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus can be identified in late-onset neonatal pneumonia. Viruses are the main cause of pneumonia in older infants and toddlers between 30 days and 2 years old. In children 2 to 5 years old, respiratory viruses are also the most common. The rise of cases related to S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae type B is observed in this age group. Mycoplasma pneumonia frequently occurs in children in the range from 5 to 13 years old; however, S. pneumoniae is still the most commonly identified organism. Adolescents usually have the same infectious risks as adults. It is important to consider tuberculosis (TB) in immigrants from high prevalence areas, and children with known exposures. Children with chronic diseases are also at risk for specific pathogens. In cystic fibrosis, pneumonia secondary to S. aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa is ubiquitous. Patients with sickle cell disease are at risk of infection from encapsulated organisms. Children who are immunocompromised should be evaluated for Pneumocystis jirovecii, cytomegalovirus, and fungal species if no other organism is identified. Unvaccinated children are at risk for vaccine-preventable pathogens.

Epidemiology

There are an estimated 120 million cases of pneumonia annually worldwide, resulting in as many as 1.3 million deaths. Younger children under the age of 2 in the developing world, account for nearly 80% of pediatric deaths secondary to pneumonia. The prognosis of pneumonia is better in the developed world, with fewer lives claimed, but the burden of disease is extreme, with roughly 2.5 million cases yearly. Approximately a third to half of these cases lead to hospitalizations.

The introduction of the pneumococcal vaccine has significantly lowered the risk of pneumonia in the United States.

Pathophysiology

Pneumonia is an invasion of the lower respiratory tract, below the larynx by pathogens either by inhalation, aspiration, respiratory epithelium invasion, or hematogenous spread. There are barriers to infection that include anatomical structures (nasal hairs, turbinates, epiglottis, cilia), and humoral and cellular immunity. Once these barriers are breached, infection, either by fomite/droplet spread (mostly viruses) or nasopharyngeal colonization (mostly bacterial), results in inflammation and injury or death of surrounding epithelium and alveoli. This is ultimately accompanied by a migration of inflammatory cells to the site of infection, causing an exudative process, which in turn impairs oxygenation. In the majority of cases, the microbe is not identified, and the most common cause is of viral etiology.

There are four stages of lobar pneumonia. The first stage occurs within 24 hours and is characterized by alveolar edema and vascular congestion. Both bacteria and neutrophils are present.

Red hepatization is the second stage, and it has the consistency of the liver. The stage is characterized by neutrophils, red blood cells, and desquamated epithelial cells. Fibrin deposits in the alveoli are common.

The third stage of gray hepatization stage occurs 2-3 days later, and the lung appears dark brown. There is an accumulation of hemosiderin and hemolysis of red cells.

The fourth stage is the resolution stage, where the cellula infiltrates is resorbed, and the pulmonary architecture is restored. If the healing is not ideal, then it may lead to parapneumonic effusions and pleural adhesions.

In bronchopneumonia, there is often patch consolidation of one or more lobes. The neutrophilic infiltrate is chiefly around the center of the bronchi.

History and Physical

In many cases, complaints associated with pneumonia are nonspecific, including cough, fever, tachypnea, and difficulty breathing. Young children may present with abdominal pain. Important history to obtain includes the duration of symptoms, exposures, travel, sick contacts, baseline health of the child, chronic diseases, recurrent symptoms, choking, immunization history, maternal health, or birth complications in neonates.

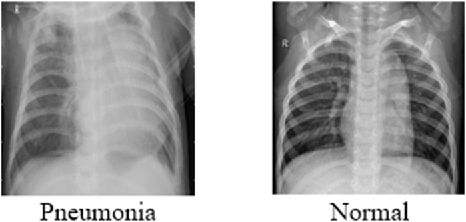

Physical exam should include observation for signs of respiratory distress, including tachypnea, nasal flaring, lower chest in-drawing, or hypoxia on room air. Note that infants may present with reported inability to tolerate feeds, with grunting or apnea. Auscultation for rales or rhonchi in all lung fields with the appropriately sized stethoscope can also aid in diagnosis. In the developed world, other adjuncts like laboratory testing and imaging can be a helpful part of the physical exam. No isolated physical exam finding can accurately diagnose pneumonia. However, the combination of symptoms, including fever, tachypnea, focal crackles, and decreased breath sounds together, raises the sensitivity for finding pneumonia on x-ray. Pneumonia is a clinical diagnosis that should take into consideration the history of present illness, physical exam findings, adjunct testing, and imaging modalities.

Differential Diagnosis

- Alveolar proteinosis

- Aortic stenosis

- Aseptic meningitis

- Asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy

- Aspiration syndromes

- Asthma

- Atelectasis

- AV septal defect, complete

- AV septal defect, unbalanced

- Bacteremia

- Birth trauma