Bacterial Tracheitis

Published .

Bacterial tracheitis (BT), also known as bacterial croup or laryngotracheobronchitis, was first described in medical literature in the 1920s, despite the name not being coined until the 1970s. Bacterial tracheitis is a potentially lethal infection of the subglottic trachea. It is often a secondary bacterial infection preceded by a viral infection affecting children, most commonly under age six. It can also be rarely seen spontaneously in the adult population, and tracheostomy-dependent patients of any age. Concern for airway protection is the mainstay of treatment as thick, mucopurulent secretions can cause airway narrowing and obstruction. On presentation, this must be distinguished from other causes of airway obstruction to allow for more expedited treatment. Treatment is aimed at the protection of the airway, assessing the need for diagnostic and/or therapeutic endoscopy, and antimicrobial therapy.

Etiology

Bacterial tracheitis is a bacterial infection of the trachea often preceded by a viral upper respiratory infection. The most common viruses implicated include Influenza A and B (type A being the most common), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), parainfluenza virus, measles virus, and enterovirus. These viruses cause airway mucosal damage via a local immune response which predisposes the trachea to the seeding of bacteria. Affected patients are usually healthy before onset, and most will recover with appropriate recognition and treatment. However, at-risk populations, including immunocompromised individuals, are prone to severe sequelae. Implicated bacteria include most commonly: Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Moraxella catarrhalis, Haemophilus influenzae type B (HiB), Haemophilus influenzae (non-typeable), and less commonly, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, and anaerobic organisms.

Epidemiology

The annual incidence of bacterial tracheitis varies between countries, with an estimated incidence of 0.1 to 1 case(s) per 100,000 children. Bacterial tracheitis has a peak incidence between the ages of three to eight years old, although it has been described in both infants and adults. Recently, a shift in clinical course and incidence of bacterial tracheitis has been noted with the disease being less severe and occurring in an older subset of patients, typically five to ten years old. Males have a slight predominance over females with various reported ratios from 1 to 1 to 5 to 1. The incidence rises in the fall and winter months, and it is more infrequent in summer or spring, which coincides with the typical seasonal viral epidemics of influenza, parainfluenza, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

Pathophysiology

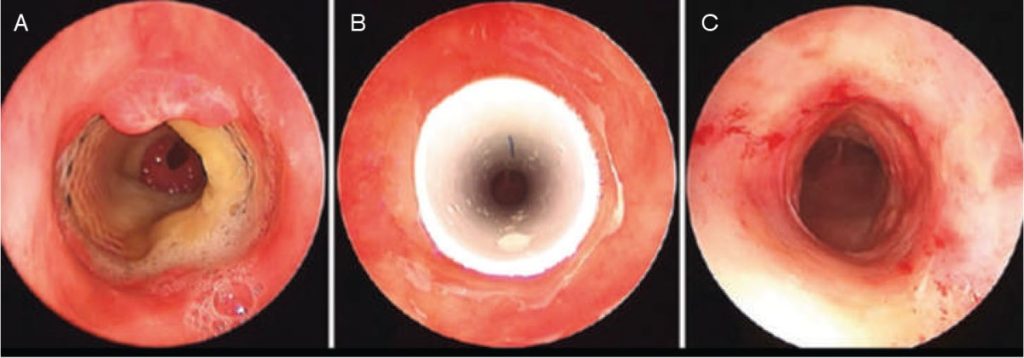

In bacterial tracheitis, opportunistic bacteria invade damaged tracheal mucosa, made of pseudostratified columnar epithelium, and stimulate local and systemic inflammatory responses. In otherwise healthy patients, this is presumed to be precipitated by a viral upper respiratory infection, while in patients with an indwelling tracheostomy tube, it can also be due to seeding from a colonized tracheostomy appliance. Local responses in the tracheal mucosa cause edema, thick mucopurulent secretions, ulceration, and mucosal sloughing, which can predispose the patient to subglottic narrowing, tracheal narrowing, and/or airway obstruction. Systemic inflammation leading to sepsis is rare but can occur in immunocompromised patients. Staphylococcus aureus has been the most commonly implicated pathogen, although reports suggest M. catarrhalis is becoming more common, especially in younger children.

History and Physical

Presentation of bacterial tracheitis can occur in various ways depending on the patient’s age and whether or not they are tracheostomy-dependent. The most common presentation in non-tracheostomy-dependent children and adults is a more insidious development with prodromal symptoms that suggest a viral respiratory tract infection. Viral symptoms including rhinorrhea, post-nasal drip, cough, fever, myalgia, and sore throat are present up to a week before the acute worsening of the patient. Patients will then develop acute airway deterioration, high fevers, hoarseness, toxic appearance, and increased mucopurulent secretions secondary to the bacterial infection. Less commonly, fulminant respiratory distress with less than 24 hours of symptoms can occur. Signs and symptoms include stridor (inspiratory or expiratory), fever, productive and painful cough, thick secretions, and tenderness of the trachea.

Drooling and tripoding are less common and suggest an alternative diagnosis such as epiglottitis, as children with bacterial tracheitis do not have as much difficulty swallowing their oral secretions. Patients with severe subglottic obstruction may have cyanosis, appear lethargic, or can be combative, suggesting hypoxemia and/or hypercarbia.

In patients who are tracheostomy-dependent, symptoms of bacterial tracheitis can include high fevers, chills, productive cough, thick mucopurulent secretions, hemoptysis, peristomal skin breakdown or cellulitis, high ventilatory peak pressures, and/or tracheostomy obstruction.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of bacterial tracheitis is primarily clinical via a thorough history and physical examination. As discussed above, patients may appear febrile, dyspneic, hoarse, stridulous, septic or toxic-appearing, and in respiratory distress. Trial with nebulized epinephrine and glucocorticoids will typically fail to show improvement in the patient’s clinical course.