Fluid Resuscitation

Published (updated: ).

The primary role of fluid resuscitation is to maintain organ perfusion (hemodynamics) and substrate (oxygen, electrolytes, among others) delivery through the administration of fluid and electrolytes. An enteral route can be used; however, when oral intake is not possible, clinicians can replace fluid losses by intravenous (IV) administration.

Anatomy and Physiology

Body fluids are distributed into intracellular and extracellular compartments. Intracellular compartment contributes to most total body water. Extracellular fluids are within the interstitial, intravascular, and trans-cellular spaces. Predominant electrolytes in body fluids are sodium and potassium, where sodium is the dominant cation in the extracellular fluid and potassium is the dominant cation in the intracellular fluid. Sodium and magnesium are the other minor cations in the intracellular fluids and are electrochemically balanced by phosphate, sulfate, and bicarbonate anions. Calcium and magnesium are the other cations found in minor concentrations in the extracellular fluid, and they are balanced by chloride, bicarbonate, phosphate, and sulfate anions.

Indications

Trauma

Trauma is the number one cause of death in the United States for individuals between 1 and 44 years of age. Among them, hemorrhagic shock is the primary cause of death for 30% to 40% in the first 24 hours following injury. Loss of blood triggers a compensatory hemodynamic response to restore volume. The compensatory mechanisms click in when there is acute blood loss of more than 5% to 10%. Blood losses of greater than 20% will require fluid resuscitation to support the continued delivery of oxygen to vital organs.

Trauma and acute blood loss trigger compensatory mechanisms aimed at restoring volume deficits to maintain adequate perfusion of vital organs. Trans-capillary refill occurs first and involves the shift of fluid from the interstitial space into the intravascular space secondary to increased capillary permeability and decreased plasma colloid osmotic pressure. The resultant effect is the sequestration of about 1 liter of fluid into intravascular spaces. Activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system occurs next, activated by the reduction in renal perfusion and causing sodium and water retention by the kidneys.

The overall goal is to replace the fluid lost from the interstitial compartment to the intravascular spaces. But one must exercise caution, because an aggressive large volume fluid resuscitation may lead to hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy. Typical indications for resuscitation are a systolic blood pressure of less than 80 to 85 mm Hg or one that is rapidly decreasing and/or a decline in mental status without evidence of head trauma.

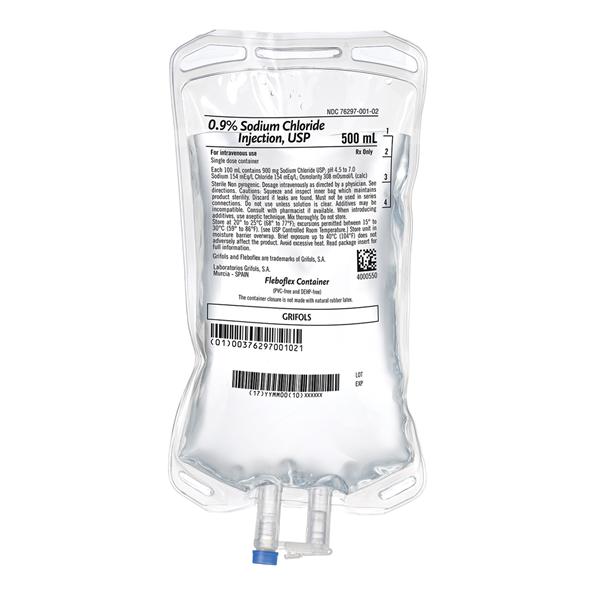

Two major types of fluids used for resuscitation are colloids which specifically expand the intravascular volume and crystalloids, which briefly expand the intravascular volume and quickly re-distribute into the interstitial compartment. For resuscitation, crystalloids are given as 1- to 2-liter bolus in patients with hemorrhagic shock. However, recent studies using colloids favor permissive hypotension. For example, in patients with penetrating trauma, aggressive fluid resuscitation may exacerbate bleeding, so the emphasis is on administering small boluses of fluid (250mL) allowing a low systolic blood pressure equal to 90 mm Hg or mean blood pressure equal to 50 mm Hg until one achieves sustained hemorrhagic control. This strategy has been shown to improve survival and reduce the amount of fluid replaced.

It is important to remember that it is only safe to allow low blood pressures when there is good clinical evidence of adequate organ perfusion indicated through adequate urine output and mental status. Crystalloids should ideally serve as a bridge to maintain perfusion until blood products are available in hemorrhagic shock. Hence, one should consider limited 500-ml bolus doses in patients without or impending shock until blood products become available.

Sepsis

Sepsis is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients with mortality ranging between 20% to 45%. Uncontrolled inflammation, tissue hypoperfusion, microvascular and micro-cellular level abnormalities, and dysfunction are critical determinants in the progression toward multiple organ failure, which predict poor outcomes. Septic shock is defined as refractory hypotension that results from a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) caused by or suspected to be from an infection.

The key characteristic of septic shock is systemic vasodilation which results in hypovolemia, decreased tissue perfusion and decreased oxygen delivery. The main aim of fluid resuscitation is to restore hemodynamics to optimize tissue perfusion and ultimately the tissue oxygen delivery.

For resuscitation, one should give crystalloids at a dose of 30 mL/kg of ideal body weight as early as possible, typically within the first 3 hours.

Contraindications

0.9% saline should be used with caution in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage or postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) as these conditions can themselves cause alterations in serum sodium concentration (hypo or hypernatremia). Colloids such as hydroxyethyl starch (HES) should be avoided in septic shock because of their adverse effects on coagulation and renal function.

Complications

Large amounts of intravenous fluids can cause hypervolemia and potentially electrolyte imbalance. In septic shock, overzealous use of intravenous fluids for a prolonged period can cumulatively increase the total body water, especially in patients with compromised renal, cardiac or hepatic function. This excess free water often accumulates in the extravascular lung (pulmonary edema) and subcutaneous tissues (pedal or sacral edema) and poses problems during recovery, for example, failure to wean from the ventilator and muscle weakness, both of which will cause prolongation of hospital stay and increase the associated risk of nosocomial complications. A 0.9% saline causes hyperchloremic acidosis following excess use and is associated with nephrotoxicity.