Right Heart Failure

Published .

When addressing heart failure, most commonly, the left ventricle (LV) is the topic of discussion, and the right heart overlooked. However, the right ventricle (RV) is unique in structure and function and is affected by a set of disease processes that rival that of the LV. This article will review the normal structure and function of the RV, describe the pathophysiology of RV failure (RVF), and detail the medical and surgical management of the various disease processes during which RVF occurs.

Etiology

Right ventricular failure (RVF) is most commonly a result of left ventricular failure (LVF), via pressure and volume overload.

In addition to LVF, there are other conditions of pressure overload that lead to RVF. These include transient processes such as:

- Pneumonia

- Pulmonary embolism (PE)

- Mechanical ventilation

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

Furthermore, chronic conditions of pressure overload may lead to RVF. These include:

- Primary pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and secondary pulmonary hypertension (PH) as seen in chronic-obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or pulmonary fibrosis)

- Congenital heart disease (pulmonic stenosis, right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, or a systemic RV).

The following conditions result in volume overload causing RVF:

- Valvular insufficiency (tricuspid or pulmonic)

- Congenital heart disease with a shunt (atrial septal defect (ASD) or anomalous pulmonary venous return (APVR)).

Another important mechanism that leads to RVF is intrinsic RV myocardial disease. This includes:

- RV ischemia or infarct

- Infiltrative diseases such as amyloidosis or sarcoidosis

- Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD)

- Cardiomyopathy

- Microvascular disease.

Lastly, RVF may be caused by impaired filling which is seen in the following conditions:

- Constrictive pericarditis

- Tricuspid stenosis

- Systemic vasodilatory shock

- Cardiac tamponade

- Superior vena cava syndrome

- Hypovolemia.

Epidemiology

RVF is most often a result of LVF, and patients with biventricular failure have a 2-year survival of 23% versus 71% in patients with LVF alone.

Pathophysiology

During fetal development, the RV accounts for approximately 66% of the cardiac output, and via the ductus arteriosus and foramen ovale, shunts blood to the lower body and placenta. At birth, exposure to oxygen and nitric oxide, as well as lung expansion, leads to a rapid decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). The lungs, which were bypassed in utero, become a low-pressure, highly distensible circuit. The thick-walled fetal RV becomes thinner.

Anatomically the structures and resulting function of the RV and the LV are vastly different. For example:

- The LV is elliptical and made of thick muscle fibers wrapped in two anti-parallel layers separated by a circumferential band. This results in a complex contraction that involves torsion, thickening, and shortening.

- The RV, in contrast, takes a triangular and crescentic shape and is made up of both a superficial layer that runs circumferentially and parallels to the atrioventricular groove and a deeper layer that runs longitudinally from the base to the apex. Because of its structure, the contraction of the RV is limited to longitudinal shortening of the tricuspid annulus towards the apex. The RV free wall is displaced inward toward the septum and traction is created by the septum as it moves toward the LV in systole.

- The RV is more heavily trabeculated and contains a circumferential moderator band at the apex.

- The tricuspid valve (TV) is unique in that it has a large annulus and is tethered by greater than three papillary muscles which make it vulnerable to structural deformation under sustained increased pressure or volume loading.

- Because the RV is substantially thinner than the LV with lower elastance, the RV is much more susceptible to increases in afterload. A modest change in PVR may result in a marked decrease in RV stroke volume. This is evident in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), pulmonary embolism (PE), mitral valve disease with secondary pulmonary hypertension (PH), and the adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The thinner RV is also more sensitive to the pericardial constraint.

Like the LV, contraction of the RV is preload dependent at normal physiologic filling pressures, and excessive RV filling can result in a shift of the septum towards the LV and ventricular interdependence causing impaired LV function.

Because of lower right-sided pressures and wall stress, the oxygen requirement of the RV is lower than that of the LV. Coronary blood flow to the RV is lower, as is oxygen extraction. For this reason, the RV is less susceptible to ischemic insults, and increases in oxygen demand are met via increases in coronary flow as is the case in PAH or increased oxygen extraction which occurs with exercise.

RV function is affected by atrial contraction, heart rate, and synchronicity. Each of these has important clinical implications, and RVF for any reason is a strong prognostic indicator.

The response of the RV to a pathologic load is complex. The nature, severity, chronicity, and timing (in utero, childhood or adulthood) each play a role in how the RV responds to an increased load. For example, in childhood, when confronted with congenital pulmonic stenosis, fetal right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) persists and allows the RV to compensate for the increase in afterload.

In adulthood, however, the ability of RV to tolerate a chronic increase in afterload, such as that seen in PAH, is poor. In the early stages of PAH, the RV responds to elevated pulmonary arterial pressures (PAP) by increasing contractility, with little to no change in RV size. As PAP continue to rise, the RV myocardium begins to hypertrophy, and RV stroke volume (SV) is maintained. This, however, is not enough to normalize wall stress, and subsequently, dilatation occurs. This is accompanied by rising filling pressures, decreased contractility, loss of synchronicity as the RV becomes more spherical, and dilatation of the TV annulus resulting in poor coaptation of the valve leaflets and functional tricuspid regurgitation (TR). The TR worsens the RV volume overload, RV enlargement (RVE), wall stress, contractility and cardiac output.

This differs from the response of the RV to an acute increase in afterload, such as that seen with an acute PE. In this case, the RV responds with an increase in contractility and end-diastolic volume, but does not have time for the adaptations that are seen in chronic RVF to occur, and quickly fails when unable to generate enough pressure to maintain flow.

History and Physical

As with all disease states, the initial assessment of RVF begins with a thorough history and physical examination. The acuity, severity, and etiology should be determined so that an appropriate treatment plan may be put in place.

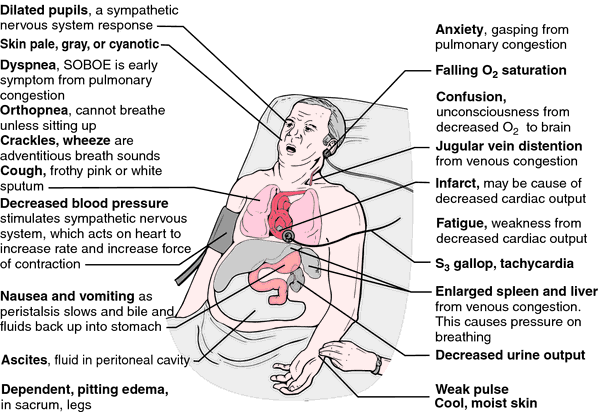

Clinically, patients present with the signs and symptoms of hypoxemia and systemic venous congestion. These include:

- Breathlessness

- Chest discomfort

- Palpitations

- Swelling.

Common findings on the exam include:

- Jugular venous distension

- Hepatojugular reflux

- Peripheral edema

- Hepatosplenomegaly/hepatic pulsation

- Ascites

- Anasarca

- S3 gallop

- TR murmur

- RV heave

- Signs of concomitant LVF

- Paradoxical pulse.

When severe, presyncope or syncope may occur when the RV is unable to maintain cardiac output. This is accompanied on the exam by the following:

- Hypotension

- Tachycardia

- Cool extremities

- Delayed capillary refill

- Central nervous system depression

- Oliguria

Differential Diagnosis

- Cirrhosis

- Community-Acquired pneumonia (CAP)

- Emphysema

- Goodpasture syndrome

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)

- Interstitial (Nonidiopathic) Pulmonary fibrosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Neurogenic pulmonary edema

- Pneumothorax imaging

- Pulmonary embolism (PE)

- Respiratory failure

- Venous insufficiency

- Viral pneumonia