Vaginal Delivery

Published (updated: ).

Vaginal delivery is safest for the fetus and the mother when the newborn is full-term at the gestational age of 37 to 42 weeks. Vaginal delivery is preferred considering the morbidity and the mortality associated with operative cesarean births has increased over time. Approximately 80% of all singleton vaginal deliveries are at full-term via spontaneous labor, whereas 11% are preterm, and 10% are post-term. Of note, with the advent of operative delivery modalities and surgical delivery modalities, the number of patients who reach spontaneous labor has decreased over time, and the induction of labor has increased.

The labor leading to the delivery is divided into 3 stages, and each stage requires specific management. Complications arise during each of the three stages, which can lead to the conversion of the anticipated vaginal delivery to operative cesarean delivery. According to the latest published data, in the USA, in 2017, there were 3,855,500 births, and 68% (2,621,010) of those were vaginal deliveries. The preterm birth rate was 9.9%, and the population’s birth rate was 11.8 per 1000.

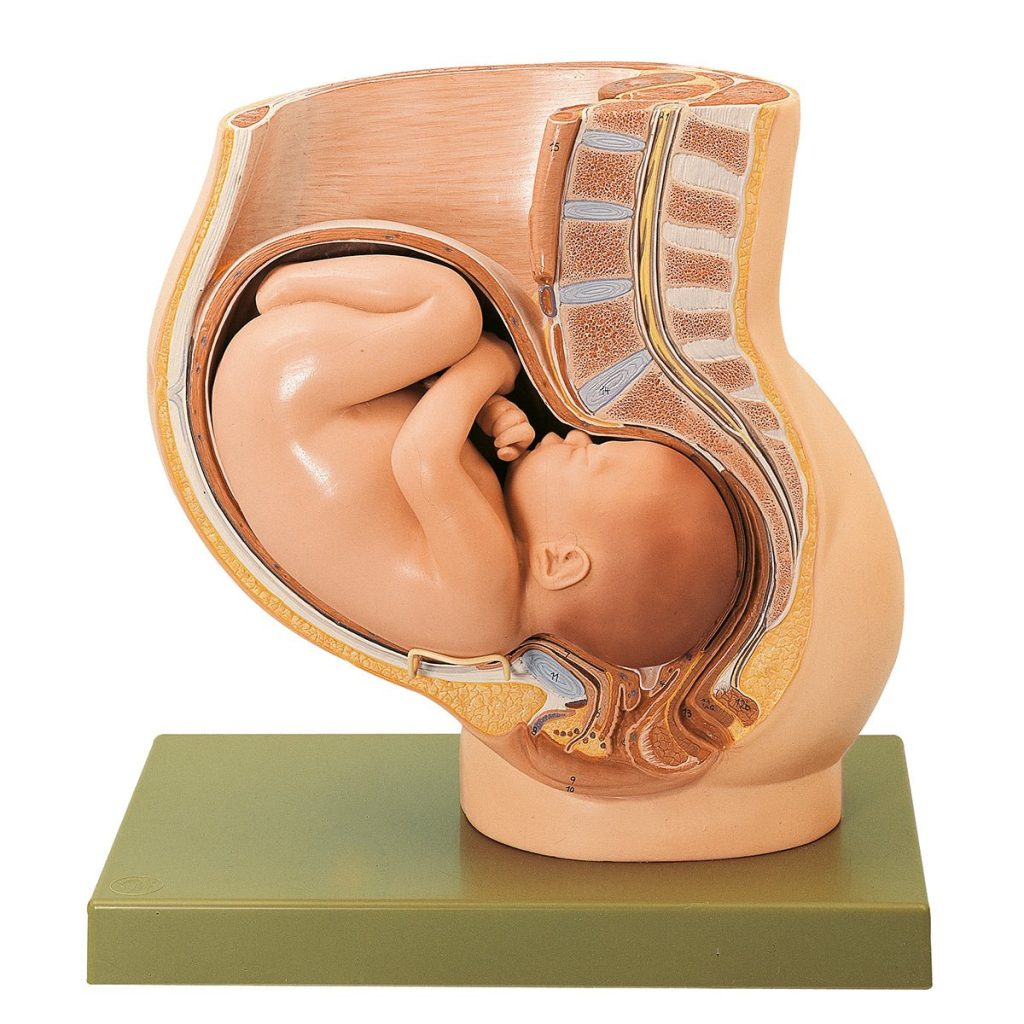

Anatomy and Physiology

The labor leading to delivery of a full-term pregnancy is divided into three stages. The management of each stage varies, and exam findings during each of the stages can help identify short-term and long-term complications for the anticipated vaginal delivery such as fetal distress and hypoxemia, cord prolapse, placental abruption, uterine rupture, permanent disability, and maternal and/or fetal death.

The first stage of labor is the longest stage of labor; it is the result of progressive and rhythmic uterine contraction which causes the cervix to dilate. The first stage of labor is divided into two sub-stages. The first sub-stage is known as the latent phase, which can last for several hours and starts from the cervical size of 0 cm to dilation of the cervix to 6 cm. The second sub-stage is known as the active phase, which includes the time from the end of the latent phase to the complete dilation of the cervix. This phase is rapid; in nulliparous women, the cervix dilates at an approximate rate of 1.00 cm/hour. It dilates slightly faster at a rate of 1.2 cm/hour in multiparous women.

The second stage of labor includes the time from complete cervical dilation, which is the end of the first stage to delivery of the fetus. Duration of this phase is variable and can last from minutes to hours; however, the maximum amount of time that a woman can be in this phase of labor depends on the parity of the patient and whether the patient has an epidural catheter placed for anesthesia.

During this stage, three clinical parameters are important to be aware of, which include fetal presentation, fetal station, and fetal position. The fetal presentation is dictated by which fetal body part first passes through the birth canal; most commonly, this is the occiput or the vertex of the head. The fetal station is determined by the relationship between the fetal head and maternal ischial spines; the station is defined from a range of -5 to +5, and 0 indicates that the fetal head is level with the maternal ischial spines. The fetal position is defined as the position of the top of the fetus’ head in comparison to the plane of the maternal ischial spines when it is born. The vertex, which is the top of the fetus’ head, normal rotates in either direction during the internal rotation portion of the cardinal movements during childbirth.

There are six cardinal movements of childbirth, all of which occur during the second stage of labor. The first of these movements is engagement, which occurs when the head of the fetus enters the lower pelvis. Then, there is flexion of the head, which enables the occiput of the head of the fetus to be in a presentation position. This flexion is then followed by descent when the fetus descends through the birth canal through the pelvis. Once the descent is complete, there is internal rotation, which enables the vertex of the fetal head to rotate away from the ischial spines located laterally. Then, there is an extension of the head, which allows the fetal head to pass the maternal pubic symphysis, and finally, there is external rotation of the head, which allows the anterior shoulder to be delivered. The second stage of labor ends once the fetus is delivered.

The final stage of labor includes the time after the child is born to the delivery of the placenta. The duration of this phase is approximately 30 minutes; during this time, as the uterus contracts, the placenta separates from the endometrium. This process begins at the lower pole of the placenta, and progress is along with the adjacent sites of placental attachment. The continual uterine contraction causes a wave-like separation in the upward direction, which causes the most superior portion of the placenta to detach last. Signs of placental detachment include a sudden gush of blood, lengthening of the umbilical cord, and cephalad movement of the uterine fundus, which becomes firm and globular once the placenta detaches. The third stage of labor concludes once the placenta completely separates and is delivered.

Indications

For full-term pregnancies, vaginal delivery is indicated when spontaneous labor occurs or if amniotic and chorionic membranes rupture. In addition, for complicated gestations or for post-term pregnancies, induction of labor is indicated, which is also an indication for vaginal delivery.

For women in spontaneous labor, the consensus in the review of the literature reveals that if the woman has regular contractions that require her focus and attention combined with either sufficient effacement (greater than or equal to 80%) and/or 4-5 cm of cervical dilation, the woman is in spontaneous labor and should be admitted to the hospital for a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery. It is important to note that woman near labor can feel regular contractions, but can present without cervical effacement or dilation and can be discharged with a follow up after routine monitoring of the fetus’ heart rate and monitoring contractions with a tocodynamometer. Subsequently, some women with cervical dilation or effacement without sufficient spontaneous contractions can be admitted for augmentation and induction of labor using oxytocin.

The rupture of membranes is another indication of vaginal delivery. This may be indicated by a sudden gush of watery-fluid reported by the mother, which may be associated with a uterine contraction. Rupture of membranes at term gestation is an indication for vaginal delivery. Management of a patient’s preterm premature rupture of membranes is dependent on the gestation of pregnancy, among other maternofetal characteristics.

Certain conditions necessitate the induction of labor as timely delivery of pregnancy is important to peripartum outcomes of both the mother and fetus. Conditions such as post-term pregnancy (defined as gestation that is greater than 42 weeks and 0 days), pre-labor rupture of membranes, gestational hypertensive disorders (preeclampsia, eclampsia), HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome, fetal demise, fetal growth restriction, chorioamnionitis, oligohydramnios, placental abruption, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, among other conditions are all indications for labor and vaginal delivery.

Contraindications

Vaginal delivery is the preferred method for childbirth; however, there are certain conditions when vaginal delivery is contraindicated. Certain conditions require immediate conversion of vaginal delivery to an emergent cesarean section for childbirth, while some conditions can spontaneously resolve, and trial of vaginal delivery can be attempted.

Conditions that require prompt cesarean section and are contraindications to vaginal delivery can be categorized by the system; certain presentations such as footling breech, frank breech, complete breech, and cord prolapse are indications for emergent conversion to cesarean section. Pathologies associated with malposition of the fetus, such as face presentation with mentum (chin in the direction of the maternal sacrum) posterior, transverse lie or shoulder presentation, and occiput posterior, should be converted to an abdominal delivery. Twin gestations when presenting twin is in a breech position, conjoined twins and mono-amniotic twins are contraindications for vaginal delivery. Abnormal placenta positions such as placenta previa, known placenta accreta, or history of uterine rupture are conditions that are contraindications for vaginal delivery. Infection such as active genital herpes outbreak is also an absolute contraindication for vaginal delivery. In the USA, higher-order births are also contraindications for vaginal delivery.

Relative contraindications also exist for vaginal delivery. There are certain conditions where vaginal delivery can be tried. Trial of Labor after Caesarean section (TOLAC) can also be attempted but is contraindicated when there is a history of multiple cesarean sections, history of placenta previa, and evidence of cephalopelvic disproportion as indicated by macrosomia. Fetal weight greater than 5000 grams in a mother with diabetes or fetal weight greater than 4500 grams in a mother without diabetes are relative contraindications for vaginal delivery.

Equipment

Ensuring proper equipment is essential to a successful vaginal delivery and to minimize fetal and maternal morbidity and mortality. Appropriate equipment is necessary to anticipate and appropriately manage improbable but realistic complications of low-risk vaginal deliveries, as 20% to 25% of all perinatal morbidity and mortality occurs in pregnancies devoid of risk factors for adverse outcomes.

Appropriate preparation includes a warm and clean room with adequate lighting and supplemental light source, a delivery bed with clean linen whose height can be adjusted, a plastic sheet to place under the mother, chlorhexidine, and wipes. There should be equipment for barrier protection such as gloves and masks. Sterile equipment includes appropriate sterile gloves, sterile instruments such as scissors, needle holders, artery forceps for cord clamping, dissecting forceps, sponge forceps, sterile blade, and cord ties.

The list of equipment needed also includes a tocodynamometer to monitor uterine contractions using an external monitor or an intrauterine pressure catheter and fetal heart rate monitor with either external heart rate monitor or an internal fetal heart rate monitor (scalp electrode). If the delivery needs assistance, either forceps or vacuum can be kept bedside to assist in vaginal delivery.