Placenta Previa

Published (updated: ).

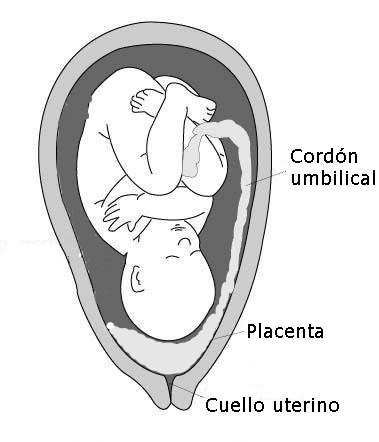

Placenta previa is the complete or partial covering of the internal os of the cervix with the placenta. It is a major risk factor for postpartum hemorrhage and can lead to morbidity and mortality of the mother and neonate. This situation prevents a safe vaginal delivery and requires the delivery of the neonate to be via cesarean delivery. Most cases are diagnosed early on in pregnancy via sonography and others may present to the emergency room with painless vaginal bleeding in the second or third trimester of pregnancy. The presence of placenta previa can also increase a woman’s risk for placenta accreta spectrum (PAS). This spectrum of conditions includes placenta accreta, increta, and percreta. Uncontrolled postpartum hemorrhage from placenta previa or PAS may necessitate a blood transfusion, hysterectomy thus leaving the patient infertile, admission to the ICU, or even death.

Etiology

The underlying cause of placenta previa is unknown. There is, however, an association between endometrial damage and uterine scarring. The risk factors that correlate with placenta previa are advanced maternal age, multiparity, smoking, cocaine use, prior suction, and curettage, assisted reproductive technology, history of cesarean section(s), and prior placenta previa. The implantation of a zygote (fertilized egg) requires an environment rich in oxygen and collagen. The outer layer of the dividing zygote, blastocyst, is made up of trophoblast cells which develops into the placenta and fetal membranes. The trophoblast adheres to the decidua basalis of the endometrium, forming a normal pregnancy. Prior uterine scars provide an environment that is rich in oxygen and collagen. The trophoblast can adhere to the uterine scar leading to the placenta covering the cervical os or the placenta invading the walls of the myometrium.

Placenta previa affects 0.3% to 2% of pregnancies in the third trimester and has become more evident secondary to the increasing rates of cesarean sections. Placenta previa is the complete or partial covering of the cervix. A low-lying placenta is where the edge is within 2 to 3.5 cm from the internal os. Marginal placenta previa is where the placental edge is within 2cm of the internal os. Nearly 90% of placentas identified as “low lying” will ultimately resolve by the third trimester due to placental migration. The placenta itself does not move but grows toward the increased blood supply at the fundus, leaving the distal portion of the placenta at the lower uterine segment with relatively poor blood supply to regress and atrophy. Migration can also take place by the growing lower uterine segment thus increasing the distance from the lower margin of the placenta to the cervix.

History and Physical

The risks factors for placenta previa include a history of advanced maternal age (age greater than 35 years old), multiparity, smoking, history of curettage, use of cocaine, and history of cesarean section(s). The relationship between advanced maternal age and placenta previa may be confounded by higher parity and a higher probability of previous uterine procedures or fertility treatment. However, it may also represent an altered hormonal or implantation environment. The nicotine and carbon monoxide, found in cigarettes, act as potent vasoconstrictors of placental vessels; this compromises the placental blood flow thus leading to abnormal placentation.

Painless vaginal bleeding during the second or third trimester of pregnancy is the usual presentation. The bleeding may be provoked from intercourse, vaginal examinations, labor, and at times there may be no identifiable cause. On speculum examination, there may be minimal bleeding to active bleeding. Sometimes the placenta can be visualized on speculum examination if the cervix is dilated. A digital examination should be avoided to prevent massive hemorrhage.

Treatment / Management

With the diagnosis of placenta previa, the patient is scheduled for elective delivery at 36 to 37 weeks via cesarean section. However, some patients with placenta previa present with complications and require urgent cesarean sections at an earlier gestational age.

Patients who present with a known history of placenta previa and vaginal bleeding should have vitals performed, and should have electronic fetal monitoring initiated. The patient should receive two large-bore intravenous lines with a complete blood count, type and screen, and have coags drawn. If she presents with substantial bleeding, then 2-4 units of blood should be crossed and matched.

Patients with excessive or continuous vaginal bleeding should be delivered via cesarean section regardless of gestational age. If bleeding subsides then expectant management is permissible if the gestational age is less than 36 weeks. If at or greater than 36 weeks of gestation then cesarean delivery is recommended. The patient should be admitted and, if qualified, receive magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection and steroids for fetal lung maturity. Bedrest, reduced activity, and avoidance of intercourse are commonly mandated, though there is no clear benefit. If the vaginal bleeding subsides for more than 48 hours and the fetus is judged to be healthy, then inpatient monitoring is continued, or the patient may be discharged for outpatient management. Inpatient vs. outpatient management depends on the stability of the patient, the number of episodes of bleeding, proximity to the hospital, as well as compliance.

Delivery

A cesarean section should optimally occur under controlled conditions. A discussion with the patient should take place during prenatal care of the diagnosis, possible complications, and the plan for cesarean section and possible hysterectomy if there is uncontrolled postpartum hemorrhage or PAS. The surgeon, anesthesiologist, nursing staff, pediatricians, and blood bank should receive notification of these patients. If there is a concern for PAS then urology, general surgery, as well as interventional radiology should have involvement as well. Communication should take place among the teams regarding the expected date of surgery, planned procedures such as uterine artery embolization, and updated imaging studies, which allows the various units to be aware of the patient if the patient presents earlier in an emergency setting.

The patient should have two large bore IV lines in place and blood crossed and matched. Uterine artery catheters can be placed before the procedure by interventional radiology for precautions as well. Regional anesthesia, spinal-epidural combination, is recommended at the time of delivery for nonurgent cases. In the event a hysterectomy is necessary, the patient can convert to general anesthesia. Regional anesthesia is considered superior to general anesthesia because of the decreased operative blood loss and the need for blood transfusion.[6] Inhaled anesthetics can lead to uterine relaxation worsening postpartum hemorrhage. During the procedure, if there is a postpartum hemorrhage, then the catheters can be inflated to decrease the blood supply to the uterus.

Differential Diagnosis

Vaginal bleeding during pregnancy can be due to numerous factors. Based on the trimester of pregnancy the differential diagnosis can vary greatly. In the first and second trimester, vaginal bleeding can be secondary to subchorionic hematoma, cervicitis, cervical cancer, threatened abortion, ectopic pregnancy, or molar pregnancy. In the third trimester, vaginal bleeding can be due to labor, placental abruption, vasa previa, or placenta previa.

The most life-threatening cause of vaginal bleeding in pregnancy that should be ruled out is placental abruption, which is placental separation before delivery, a complication in about 1% of births. Placental abruption presents with severe abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, and electronic fetal monitoring may show tachysystole and a nonreassuring fetal heart tracing; this too can lead to high morbidity in mortality to the fetus and mother secondary to hemorrhage.