Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic Syndrome

Published .

Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome (HHS) is a clinical condition that arises from a complication of diabetes mellitus. This problem is most commonly seen in type 2 diabetes. They described patients with diabetes mellitus with profound hyperglycemia and glycosuria without the classic Kussmaul breathing or acetone in the urine seen in diabetic ketoacidosis. This clinical condition was formerly called non-ketotic hyperglycemic coma, hyperosmolar hyperglycemic non-ketotic syndrome, and hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma (HONK).

Diabetes mellitus is a clinical condition associated with hyperglycemia as the main metabolic disorder. This is a result of an absolute or relative deficiency of insulin. Insulin is an anabolic hormone produced by the beta cells of the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. The main function of this hormone is to lower the level of glucose in the blood by promoting the uptake of glucose by the adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, known as glycogenesis. Insulin also inhibits the breakdown of fat in the adipose tissue, known as lipolysis. The metabolic effect of insulin is countered by hormones such as glucagon and catecholamines.

In type 1 diabetes, there is the autoimmune destruction of the beta cells in the pancreas. Only about 5% to 10% of all diabetes falls into this category. The most common complication of type 1 diabetes is diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

Type 2 diabetes accounts for about 90% to 95% of diabetes cases. It is most commonly seen in patients with obesity. As a consequence of obesity and high body mass index (BMI), there is resistance of the peripheral tissue to the action of insulin. The beta-cell in the pancreas continues to produce insulin, but the amount is not enough to counter the effect of the resistance of the end organ to its effect.

HHS is a serious and potentially fatal complication of type 2 diabetes.

The mortality rate in HHS can be as high as 20%, which is about 10 times higher than the mortality seen in diabetic ketoacidosis. Clinical outcome and prognosis in HHS are determined by several factors: age, the degree of dehydration, and the presence or lack of other comorbidities.

Etiology

In children and young adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, infectious diseases and disorders of the respiratory, circulatory, and genitourinary systems can cause HHS. Obesity and incessant consumption of carbohydrate-rich beverages have led to an increase in the incidence of HHS.

This is particularly true in the pediatric population, where the incidence of type 2 diabetes is on the rise.

As stated earlier, HHS is most commonly seen in patients with type 2 diabetes. If diabetes mellitus is well controlled, the chance of developing HHS is minimal. However, under certain conditions, some factors might initiate the development of HHS. The most frequent reason for this complication is infection. The infectious process in the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems can act as the causative factor. The reason for this is the insensible water loss and the release of endogenous catecholamines. Approximately 50% to 60% of HHS is attributable to an infectious etiology.

Some medications for the treatment of other ailments and conditions in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes can trigger HHS. Examples of such medications are thiazide diuretics, beta-blockers, glucocorticoids, and some atypical antipsychotics.

A cardiovascular insult like stroke, angina pectoris, and myocardial infarction can also trigger a stress response. This leads to the release of counterregulatory hormones with the resultant effect of an increased level of blood glucose, causing osmotic diuresis and dehydration, with the final result being HHS.

Epidemiology

There is insufficient data on the epidemiology of HHS. Based on some studies, close to 1% of all hospital admission for diabetes is related to HHS.

Most cases of HHS are seen in patients in the fifth and sixth decades of life. Typically DKA is more common in the younger population, with the peak age around the fourth decade of life.

In the United States, because of the increase in childhood obesity which is related to the consumption of high amounts of carbohydrate-rich diet, there is a significant increase in the incidence of type 2 diabetes. This may lead to an increased incidence of HHS in the pediatric population.

There is a disproportionally high number of African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics who are afflicted with HHS. This might be related to a high prevalence of type 2 diabetes in these particular population groups. HHS can be fatal in morbidly obese African American males.

Pathophysiology

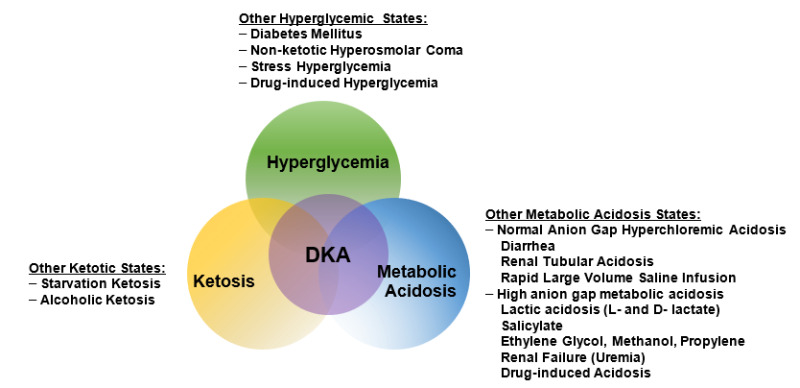

HHS has similar pathophysiology to DKA but with some mild dissimilarities. The hallmark of both conditions is the deficiency of insulin. As a consequence of deficiency of this key hormone, there is a decrease in glucose utilization by the peripheral tissue causing hyperglycemia. The peripheral tissues enter a state of “starvation.”The release of counterregulatory hormones like glucagon, growth hormone, cortisol, and catecholamines stimulates gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. This creates a system of vicious cycle where there is an increased level of glucose in the serum but decreased uptake by the peripheral tissues for tissue metabolism. The serum osmolality is determined by the formula 2Na + Glucose /18 + BUN / 2.8. The resultant hyperglycemia increases the serum osmolarity to a significant degree. The glucose level in HHS is usually above 600 mg/dL. Hyperglycemia also creates an increase in the osmotic gradient, with free water drawn out of the extravascular space due to the increased osmotic gradient. Free water with electrolytes and glucose is lost via urinary excretion producing glycosuria, causing moderate to severe dehydration. Dehydration is usually more severe in HHS as compared to DKA, and there is more risk for cardiovascular collapse.

Compared to DKA, the production of ketone bodies is scant in HHS. As a result of the deficiency of insulin, there is increased lipolysis that causes an increased release of fatty acid as an alternative energy substrate for the peripheral tissues. Beta oxidation of fatty acids produces ketone bodies: acetone, acetoacetate, and beta oxybutyric acid. Accumulation of these substrates produces ketonemia and acidemia. Acidemia from ketone bodies stimulates the kidney to retain bicarbonate ions to neutralize the hydrogen ions. This accounts for the low serum bicarbonate level in DKA.

In HHS, however, because insulin is still being produced by the beta cells in the pancreas, the generation of ketone bodies is minimal. Insulin inhibits ketogenesis. That aside, in HHS, there is a higher level of insulin with an associated lower level of glucagon. Therefore, ketonemia and acidemia, if they happen, they are very mild in HHS.

The risk of developing cerebral edema is mostly related to how fast the serum osmolarity is decreasing. If the decline is too rapid and the brain is not able to eliminate idiogenic osmoles at the same rate as the decline in serum osmolarity, then the chances of fluid moving into the brain cell and causing swelling are higher. Hence, in the treatment of HHS, the goal of treatment is a slow correction of hyperglycemia.

History and Physical

The history and physical examination are very important in the diagnosis of HHS. In many instances, there is a significant overlap in the signs and symptoms seen in HHS and DKA. In the history taking and the initial assessment, particular attention should be focused on the insulin regimen, missed dosages of oral hypoglycemic agents, overconsumption of carbohydrate-rich diet, or simultaneous use of medications that can trigger hyperglycemia or cause dehydration.

If an infectious process precedes HHS, signs and symptoms include:

- Fever

- Malaise

- General weakness

- Tachypnea

- Tachycardia

If the precipitating factor is a cardiac or vascular condition, signs and symptoms will include:

- Chest pain

- Chest tightness

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Palpitations

The typical clinical presentation of patients with HHS is increased urination (polyuria) and increased water intake (polydipsia). This is a result of the stimulation of the thirst center in the brain from severe dehydration and increased serum osmolarity. Weakness, malaise, and lethargy can also be part of the complaints.

Severe dehydration from HHS can also affect the skin and integumentary system. Typically, the skin and the oral mucosa are dry with a delayed capillary refill.

The most important distinguishing factor in HHS is the presence of neurological signs. Decreased cerebral blood flow from severe dehydration can cause:

- Focal neurological deficit

- Disturbance in visual acuity

- Delirium

- Coma

A system-based approach is necessary for the physical assessment:

- General appearance: Patients with HHS are generally ill-appearing with altered mental status

- Cardiovascular: Tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, weak and thready pulse

- Respiratory: Rate can be normal, but tachypnea might be present if acidosis is profound

- Skin: Delayed capillary refill, poor skin turgor, and skin tenting might not be present even in severe dehydration because of obesity

- Genitourinary: Decreased urine output

- Central Nervous System (CNS): Focal neurological deficit, lethargy with low Glasgow coma score, and in severe cases of HHS, the patient might be comatose.

The physical examination should also focus on other comorbidities associated with diabetes mellitus. Acanthosis nigricans, oral thrush, vulvovaginitis, and multiple pustular skin lesions might all indicate poor glycemic control. This is particularly important if HHS is the initial presentation of type 2 diabetes.