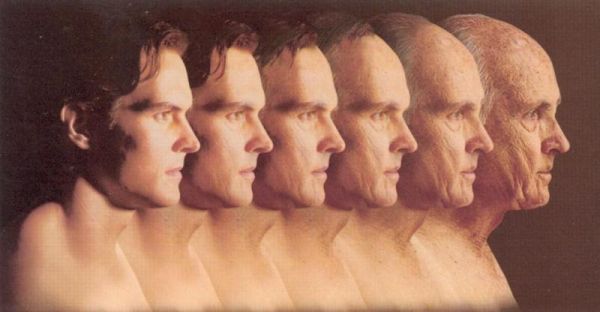

The Aging Process

Published (updated: ).

Normal aging affects all physiological processes. Subtle irreversible changes in the function of most organs can be shown to occur by the third and fourth decades of life, with progressive deterioration of pathological changes from one or more of the diseases encountered with increased prevalence in the older age group.

Cardiovascular System

Heart

Cardiac output decreases linearly after the third decade at a rate of about 1 percent per year in normal subjects otherwise free of cardiac disease. Due to the small decrease in surface area with age the cardiac index falls at a slightly slower rate of 0.79 percent per year. The cardiac output of an 80-year-old subject is approximately half that of a 20-year-old. The basis of this decrease in cardiac function is unknown but may relate to one of several factors.

First, senescent cardiac muscle has a decreased inotropic response to catecholamines, both endogenous and exogenous, and, perhaps of more clinical significance is a decreased response to cardiac glycosides. Second, with aging there is an associated increase in diastolic and systolic myocardial stiffness, perhaps due to increased interstitial fibrosis in the myocardium. Third, there is a progressive stiffening of arteries with age, particularly of the thoracic aorta, leading to an increased afterload of the heart. And finally, in autopsy studies as many as 78 percent of subjects older than 70 have been shown to have amyloid deposits in the myocardium, predominantly in the atria, but also in the ventricles and pulmonary vessels.’ When amyloid is present in the ventricles and vessels it may lead to congestive failure, often with conduction defects. Cardiac amyloidosis may be a relative contraindication to treatment with digoxin since there appears to be an increased risk of arrhythmias.

Hypertension

A progressive increase in blood pressure after the first decade of life has long been regarded as a normal consequence of aging and was the basis for ignoring the presence of hypertension in the elderly. Only in the past decade or so have prospective studies provided evidence of the grave portents of hypertension for the older age group as well as the young and the potential preventive value of early treatment. The elevation with age is more pronounced for systolic than diastolic pressure. When hypertension is defined as a systolic blood pressure of greater than 160 mm of mercury and simultaneously a diastolic of greater than 95 mm of mercury, approximately 16 per cent of the general adult population is hyper tensive but about 50 percent of those over age 65 are hypertensive.

Arteriosclerosis and Coronary Artery Disease

Thickening of the walls of arteries with hyper plasia of the intima, collagenization of the media and accumulation of calcium and phosphate in elastic fibers progressively occurs with aging.

Respiratory System

Lung Volume

A linear decrease of vital capacity is found that amounts to a decrement of about 26 ml per year for men and 22 ml per year for women starting at age 20. The total lung capacity remains constant, however, and thus the residual volume increases with age. The ratio of residual volume to total lung capacity (RV/TLC) is about 20 percent at age 20 and increases to 35 percent by age 60, with most of this increase in RV/TLC occurring after age 40. In most studies the functional residual capacity also increases, although not as rapidly as the residual volume.

Gas Exchange

Although alveolar oxygen tension remains constant with age, arterial oxygen pressure shows a progressive decrease, thus increasing the alveolar arterial oxygen difference. Most of this decrease in arterial oxygen pressure results from a mismatch of ventilation and perfusion. The elastic recoil of the lungs decreases with age and thus there is a greater tendency for airways to collapse. This is measured as an increase in “closing volume” which increases linearly above the age of 20. Airway closure occurs predominantly in the dependent zones of the lung and in the upright position this will result in a ·ventilation perfusion mismatch because more perfusion occurs in the lower lobes. Although an age-related decrease in carbon monoxide diffusing capacity has been shown, it is unclear whether this contributes to the reduction in arterial oxygen pressure.

Infections

It is well known that elderly patients have a pronounced increase in incidence of pneumonia, both bacterial and viral, compared with younger persons. Although much of this may be due to a general depression of immune system function, other more specific factors may play a role. Pneumonia generally results from aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions and such aspiration appears more frequent in the elderly. Perhaps of even greater importance, the normal mechanical clearing of the tracheobronchial tree by the mucociliary apparatus is significantly slower in nonsmoking older persons than in their younger counterparts. Finally, due perhaps to poor oral hygiene, decreased flow of saliva or difficulty with swallowing, older persons have a higher rate of colonization of their oropharynx with Gram-negative bacilli than do younger persons.

Genitourinary System

Kidneys

A gradual decrease in the volume and weight of the kidneys occurs with aging so that by the ninth decade renal size is about 70 percent of that of the third decade.

Bladder

Urinary incontinence has been found in 17 per cent of men and 23 percent of women older than 65 years. In about half of the women and a fifth of the men this was due to stress incontinence alone. The capacity of the bladder decreases with age from about 500 to 600 ml for persons younger than 65 to 250 to 600 ml for those older than 65. Perhaps more important, in younger persons the sensation of needing to void occurs when the bladder is little more than half filled but in many who are older the sensation occurs much later or sometimes not at all, leading to overflow incontinence. These changes appear to be due more often to central nervous system disease than to bladder dysfunction.

Prostate

Enlargement of the prostate occurs in most older men; by age 80 more than 90 percent of men have symptomatic prostatic hyperplasia with varying degrees of bladder neck obstruction and urinary retention. Prostate surgery is required in 5 percent to 10 percent of all men at some time.

Gastrointestinal System

Esophagus

Age-related changes of esophageal function, so called presbyesophagus, are due primarily to disturbances of esophageal motility. The esophagus in an older person may have a decreased peri staltic response, an increased nonperistaltic response, a delayed transit time or a decreased relaxation of the lower sphincter on swallowing. The decrease in peristalsis and delay in transit time may lead to dysphagia with a voluntary curtailment of caloric consumption. Nonperistaltic contractions are found almost exclusively in the elderly. They occur in the lower two thirds of the esophagus and are the cause of the “corkscrew” esophagus seen on barium swallow studies. De creased relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter on swallowing is the basis of achalasia and is more common in the elderly population.

Stomach

The incidence of atrophic gastritis increases significantly with age. In a Scandinavian study approximately 40 percent of apparently healthy subjects older than 65 had evidence of atrophic gastritis. At present, atrophic gastritis is divided into type A which is confined to the body and fundus sparing the antrum and type B which is associated with atrophy of both antral and fundic glands.

Colon

A decrease in intestinal motility occurs with age. The colon becomes hypotonic, which leads to increased storage capacity, longer stool transit time and greater stool dehydration. These are all etiologic factors in the chronic constipation that plagues the aged. Laxative abuse therefore results and is the most common cause of diarrhea in the elderly. A high-fiber diet is the treatment of choice and this can best be achieved by prescribing a diet rich in bran. Whether or not constipation is an etiologic factor in diverticulosis remains unclear but age certainly is. Diverticula are uncommon below the age of 40 but steadily increase there after until nearly 50 percent of those older than 80 have diverticulosis. Symptoms are present in only about 20 percent to 25 percent of those who are affected and severe disease with inflammation and bleeding occurs in a much smaller number.

Sphincter Control

Loss of control of the internal and external anal sphincters in the elderly in the presence of essentially normal cognitive function is a most emotionally traumatic and demeaning experience. The resulting fecal incontinence is one of the major causes for admission of many otherwise healthy persons to long-term care facilities. Recent studies have shown the cause to be a loss of tone of the external rectal sphincter. Biofeedback techniques allowed the regaining of sphincter and bowel control in as many as 70 percent of a group of patients studied.

Liver and Biliary Tract

The liver decreases in weight by as much as 20 percent after the age of 50 but perhaps because of its large reserve capacity this attrition is not reflected by a decrease in the usual liver function tests. Although tests of liver function show little or no change with age, a large number of drugs such as diazepam and antipyrine are known to be metabolized more slowly by the liver in the elderly. This alteration in hepatic drug metabolism may be due to a decrease in the appearance, amount or distribution of the smooth endoplasmic reticulum. Biliary tract disease incidence of cholelithiasis increases greatly with age. In a large autopsy series of subjects older than 70 years, 30 percent had gallstones and another 5 percent had previously had a cholecystectomy. In general, surgical operation is indicated in patients with gallstones, even if asymptomatic, since the risk of complications in an elderly patient is greater than the risk of operation.

Endocrine System

Glucose Homeostasis

Increasing age results in a progressive deterioration in the number and the function of insulin producing beta cells. The capacity of these cells to recognize and respond to changes in glucose concentration is impaired. In elderly subjects a greater proportion of the insulin released into the circulati0n in response to a glucose challenge is in the form of the inactive precursor proinsulin than in their younger counterparts. Of perhaps even greater importance is the development of progressive peripheral insulin resistance with age. Compared with younger persons the elderly have a relative decrease in lean body mass with a relative increase in adiposity.

Although diabetic ketoacidosis and lactic acidosis are uncommon in elderly diabetic persons, hyperosmolar nonketotic coma occurs with some frequency. As already discussed, there is a decrease in the renal concentrating function with age as well as a decrease in the maximal reabsorption of glucose. Thus, even mild hyperglycemia may lead to osmotic diuresis. This will cause further hyperglycemia and ultimately dehydration. The dehydration may lead to vascular insufficiency in elderly patients and they may become obtunded and refuse to drink; rapid progression to coma may then ensue. This syndrome is frequently precipitated or exacerbated by a myocardial infarction, pneumonia or urinary tract infection.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterized by a decrease in bone mass which may result in mechanical failure of the skeleton. The decrease in bone mass is an age-related phenomenon. Beginning in the fourth decade there is a linear decline in bone mass at a rate of about 10 percent per decade for women and 5 percent per decade for men. Thus, by the eighth and ninth decades 30 percent to 50 percent of the skeletal mass may be lost. The decrease in bone mass is due to a relative increase of bone resorption over formation but the basis of this is unknown. Hormonal factors certainly play a role since women are more susceptible than men and the rate of development of osteoporosis in women accelerates after menopause. Moreover, low-dose estrogen therapy can arrest or retard bone loss if begun shortly after the menopause.

Menopause

Nowhere are the development of age-related changes more apparent than in the human female. Menopause occurs because of the disappearance of oocytes from the ovary through ovulation and atresia. Little is understood about the process of ovarian atresia and whether it is due to primary ovarian failure or secondary to hypothalamic-pituitary changes.

Several consequences of the menopause deserve mention. First is the vasomotor instability or hot flashes. Two thirds to three quarters of menopausal women will experience flushing, with 80 percent having the symptoms for longer than one ‘year and 25 percent to 50 percent for more than five years. Changes in skin temperature, skin resistance, core temperature and pulse rate occur during the flush. Besides being a major disturbance while women are awake, the hot flashes may occur during sleep, leading to waking episodes. Insomnia with possible physiologic and psychologic disturbances may thus result.

It is well known that arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease is unusual in women before the menopause. The precise protective mechanism of ovarian function is not known, but premenopausal women have a higher ratio of high-density lipoproteins to low-density lipoproteins than do post menopausal women. Osteoporosis with its relation to the menopause has already been discussed. Changes of the skin occur with age and the recent demonstration of estrogen receptors in the skin of mice suggests that estrogens could have direct effects on aging of the skin.

Skin

Epidermis

Atrophy of the epidermis occurs with age and is most pronounced in exposed areas: face, neck, upper part of the chest, and extensor surface of the hands and forearms. In addition to the thinning of the epidermis there is notable flattening of the dermal epidermal junction with effacement of both the dermal papillae and the epidermal rete pegs. The turnover rate of cells in the stratum corneum decreases with age and in persons older than 65 it takes 50 percent longer to re-epithelialize blistered skin than in young adults. The decrease in epidermal cell growth and division causally contribute to the increased incidence of decubitus ulcers in older patients.

Dermis

Dermal collagen becomes stiffer and less pliable with age; elastin is more cross-linked and has a higher degree of calcification. These changes cause the skin to lose its tone and elasticity, resulting in sagging and wrinkling. An age-related decrease in the number of dermal blood vessels also develops. This relative ischemia of the skin may also play a pathogenetic role in the development of decubitus ulcers.

Musculoskeletal System

Muscle

The age-dependent decline in lean body mass is well known and is primarily due to loss and atrophy of muscle cells. Some muscles, such as the diaphragm, show few if any changes while others, such as the soleus, show pronounced infiltration by collagen and fat. Age-related changes also occur in the innervation of muscle but the exact pathologic process is not well understood.

Skeletal

Degenerative joint disease occurs in 85 percent of persons older than 70 years of age and is a major cause of disability. It affects both the peripheral and axial skeleton and is characterized by degeneration of cartilage, subchondral bone thickening and eburnation, and remodeling of bone with formation of marginal spurs and sub articular bone cysts. Due to its predilection for weight-bearing joints, wear-and-tear type mechanisms must be operative. When the degenerative changes are pronounced, pain can be severe, greatly limiting the activity status of an elderly patient. Fortunately, adequate drug and surgical treatments exist but old people are truly restricted by their joints.