Geriatric Trauma

Published (updated: ).

Assessment of the geriatric trauma patient is unique, and this population requires special attention. As the elderly population increases, the number of geriatric trauma patients also rises. Age-related changes can make caring for geriatric patients challenging and places them at greater risk of morbidity and mortality. Geriatric patients often suffer from mild to severe cognitive impairment, cardiovascular, as well as pulmonary and other organ system insufficiency that can result in general frailty. These age-related physiologic changes often limit the geriatric patient’s response to traumatic injury and place them at high risk of complications and death compared to younger counterparts.

Etiology

Falls are the most common mechanism of injury followed by motor vehicle collisions and burns. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2014 alone, older Americans experienced 29 million falls causing seven million injuries and costing an estimated $31 billion in annual Medicare costs. Determination of the cause of the fall is an important element of the care plan for each patient. It is important to determine if the fall was the result of an isolated mechanical process or a result of a systemic condition that could put the patient at risk for additional falls. Factors that must be considered include the patient’s functional status prior to the fall, location and circumstances of the fall.

Even if a reliable mechanical cause of the fall can be established, a complete medical evaluation should be considered to evaluate for a pathological condition that caused the fall. Occult anemia, electrolyte abnormalities, disorders of glucose metabolism should be considered.

Attention should be paid to the possibility of cardiovascular causes of the fall that include orthostatic hypotension, dysrhythmia and myocardial infarction. Other pathological states that can lead to falls include infection from urinary, pulmonary or soft tissue sources. Neurologic disorders such as primary or secondary seizures should be on the differential diagnosis. The role of polypharmacy and potential disruptions to normal physiologic function cannot be understated.

Epidemiology

Trauma is the fifth leading cause of death in the elderly population and accounts for up to 25% of all trauma admissions nationally. Special considerations include multiple comorbidities, polypharmacy, decreased functional reserve, and increased morbidity and mortality, compared to younger adults.

As the world population continues to age, geriatric traumas will continue to increase. Mortality increases after age 70 when adjusting for injury severity score. Pre-hospital geriatric trauma triage criteria improve identification of those needing trauma center care.

Pathophysiology

There are many anatomic and physiologic changes associated with normal aging which need to be understood to best diagnose and treat geriatric trauma patients. As we age, all our organ systems deteriorate with time and lose their underlying ability to function as they once optimally had at a younger age. This leads to significant considerations that must be undertaken when taking care of the geriatric trauma patient.

Nutrition

Elderly patients may present with various degrees of malnutrition due to either or both protein or total caloric intake as well as various mineral and supplement deficiencies. This can be secondary to a variety of reasons such as living on a fixed income, inability to obtain appropriate food from stores, reduced desire to eat, poor taste, inability to prepare meals and feed oneself. Nutritional deficiencies have significant effects on the host including decreased ability to heal and immune suppression with an inability to fight off infection. The host then becomes more susceptible to an insult and is at risk for further morbidity and mortality.

Integument/Musculoskeletal

Elderly patients have a decrease in lean body mass, loss of tissue elastance, thinning of the skin and an overall increase in total body fat. The thinning of skin makes it much harder for thermoregulation making geriatric patients much more susceptible to hypothermia even when in warm weather conditions. Skin becomes much less resistant to shearing forces as the overall elastic content decreases making it much more susceptible to skin tears and avulsions even with minor energy transfer. An increase in total body fat results in a larger volume of distribution which needs to be considered with medication administration. Loss of lean muscle mass and overall bone density via demineralization processes such as osteopenia and osteoporosis lead to less strength, loss of locomotion, balance, and ability to produce heat through shivering. Furthermore, loss of bone density leads to a higher risk of fracture with a lower energy transfer associated with more minor injury mechanisms.

Neurologic

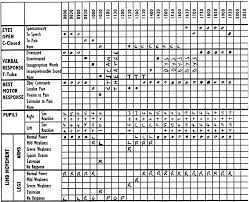

Neurohumoral responses in the elderly patient are often blunted leading to a slower and often less vigorous response to stimuli. Elderly patients often have some level of neurocognitive decline and often present with reduced sensation to nervous stimuli. Co-morbidities such as diabetes can lead to peripheral neuropathy which can lead to occult wounds with insidious infections developing, loss of proprioception and a greater risk of injuries from falls.

The central nervous system is also affected with aging, directly from normal parenchymal atrophy as well as through systemic changes such as a decreased ability to auto-regulate blood flow and underlying atherosclerotic cerebrovascular disease. Elderly patients are also usually on a myriad of medications which often have an effect on the neurologic system as well which could lead to drowsiness, loss of energy, oversedation, loss of balance and memory which can place them at an increased risk for falls, motor vehicle accidents or other injury mechanisms.

The brain parenchyma itself also atrophies and loses volume as we age which leads to stretching of the bridging dural veins. When an elderly patient falls and strikes their head or has a sudden inertial change, these veins are at high risk for rupture leading to subdural hemorrhage development. Compounded with the fact the brain itself shrinks in size but the calvarium maintains a fixed volume, clinical changes associated with intracranial hypertension often present in a delayed fashion as it takes more blood volume to lead to brain compression and shift. This is also somewhat protective in that elderly patients may not have the acute cerebral herniation as their younger counterparts and may not need surgical intervention to evacuate the hemorrhage.

Cardiovascular

The heart with aging becomes stiffer and therefore is less compliant and loses the ability to contract harder to obtain a greater output when seeing a larger preload. (Frank-Starling Law of the Heart) Furthermore, as we age the cardiac conduction system becomes more fibrotic and the myocardium becomes less responsive to neurohumoral effects. This all leads to a decreased ability for the geriatric trauma patient to preserve their cardiac output which is defined as the product of heart rate and stroke volume. (cardiac output = heart rate * stroke volume) This has clinical consequences for the elderly patient such that even for relatively mild hypovolemia, whether due to poor intake with associated dehydration or volume contraction or related to injury with hemorrhage, the resultant drop in pre-load significantly affects the overall cardiac output. Coupled with a desensitized vascular system to neurohumoral effects, there is less ability for the systemic vascular resistance to increase the peripheral blood pressure or for the venous system to contract, decreasing venous capacity and increasing preload to make up for this loss.

Polypharmacy also has a multitude of effects on the cardiovascular system in this patient population in which beta-blockade, calcium-channel blockers, and cardiac glycosides are common which leads to negative inotropic, dromotropic and chronotropic effects. Under normal circumstances this is the desired effect of the medication, however, with an acute insult, these medications prevent the host from amounting a normal physiologic response to compensate and maintain homeostasis.

Shock, defined as global tissue hypoperfusion is often clinically defined as a systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg. This definition is often incomplete for many patients especially those who are geriatric trauma patients over the age of 65. Current literature supports a systolic blood pressure of 110 mmHg to be a better benchmark which should be used for this purpose to identify occult shock.

Pulmonary

Overall pulmonary function is found to deteriorate in older adults. Commonly, the elderly have less functional residual, vital and total lung capacities and on formal pulmonary function testing, they often are found to have lower forced expiratory volumes over one second as well as forced vital capacity. The respiratory reserve is therefore limited and the ability to adapt compensatory physiologic processes to hypoxia, hypercarbia and correct metabolic disturbances such as acidosis is blunted. Clinically this is important to consider as even small perturbations to the elderly patient may manifest in respiratory failure and often the clinical signs or symptoms may be subtle, and the astute clinician should be aware of their insidious nature.

Additionally, as elderly patients lose their lean muscle mass, their ability to recruit secondary respiratory muscles is decreased. Compounded with loss of tissue elastance and greater total body fat deposition there is a decrease in chest wall compliance. Suboptimal nutritional intake also factors into this as the patients often suffer from inanition and cannot provide adequate metabolic supply for the additional need which leads to respiratory failure. Atelectasis is very common in this patient population which leads to underlying ventilation to perfusion mismatch with a resultant increase in pulmonary shunting.

A pulmonary toilet is also decreased as we age and there is often chronic airway colonization with microbes. The normal pseudostratified ciliated epithelium and goblet cells which are responsible for the mucociliary escalator fail to remove microbes and particulate matter from the lower airways and the elderly patient’s cough is often weak due to loss of muscle mass which prevents effective pulmonary hygiene. Chronic aspiration due to dysphagia is often seen in this patient population as well which significantly affects the underlying pulmonary function and should be considered in all geriatric patients who have a history of obesity, sedating medications, gastroparesis associated with diabetes or reflux to prevent worsening aspiration and respiratory failure if laid in the supine position. Strict aspiration precautions and gastric tube decompression should be considered to prevent this possibly catastrophic event from occurring.

Gastrointestinal

Poor dentition leading patients to become edentulous necessitating prosthetic dentures is common. Loss of the ability to chew foods can lead to poor nutritional intake. As we age, our salivary glands also atrophy leading to less saliva production which impairs lubrication of the food bolus and makes the process of deglutition more challenging. Transfer of the food bolus from the oropharynx to the esophagus is also impaired and can lead to aspiration as prior protective aerodigestive reflexes are often blunted or absent.

Multiple medications affect the gastric lining and acidic milieu. This can lead to worsening of the protective mechanisms for the gastric wall and lead to gastritis and other forms of peptic ulcer disease. Often, the pharmaceutical alkalization of gastric acid can lead to microbial overgrowth and if aspiration does occur, it can lead to a higher rate of pulmonary infection.

Gastric and intestinal wall integrity is affected as we age leading to poor absorption of both micro and macronutrients which may worsen underlying malnutrition. Overall motility is slowed as well as the tissues become less responsive to neurohumoral and endocrine stimuli. This can lead to a higher risk of reflux and constipation in this age group.

The liver loses its overall parenchymal mass and its total blood flow also diminishes as well. This in effect leads to a worsening ability to act as a filter to help with detoxification of the host. The liver’s intrinsic ability to make proteins such as albumin is also diminished which can lead to a decrease in oncotic pressure and worsening of third-spacing of fluids. Also, free drug concentrations can increase in the face of hypoalbuminemia leading to unwanted toxicities.

A decrease in the hepatic production of thrombopoietin can lead to thrombocytopenia as there is less stimulation of the megakaryocytes in the bone marrow. Vitamin K dependent clotting factors are also diminished due to loss of hepatic synthetic function as well as less oral intake of vitamin K. Both factors can lead to a higher risk of coagulopathy in the geriatric trauma population.

Genitourinary

A higher rate of urinary incontinence is seen in both women and men of older age. This is partially due to neurohumoral desensitization of the bladder detrusor muscle. When the detrusor fails to squeeze, post-void residual volumes can increase leading to higher rates of bacterial overgrowth with infection and even lead to post-obstructive renal failure. Prostatism in men is another common cause of the inability to completely micturate and leads to mechanical urethral obstruction. Some medications that elderly patients take may lead to acute urinary retention as well. Urinary tract infection is also another very common occult cause of altered mental status in the elderly patient and should be sought early and appropriately treated if found.

Like the other organs, the kidneys also are subjected to parenchymal tissue loss as we age. The nephron load in the renal cortex is most affected. The glomerular filtration rate is decreased leading to problems with clearance of solute and reabsorption of water which in turn leads to disturbances in fluid and electrolyte homeostasis. It is not uncommon to see a decrease in an elderly patient’s creatinine as their lean muscle mass decreases as well with age and there is an associated increase in the tubular secretion of creatinine. Serum creatinine levels can be within the normal range but may be misleading as the renal function may still be grossly impaired.