Intracerebral Hemorrhage

Published (updated: ).

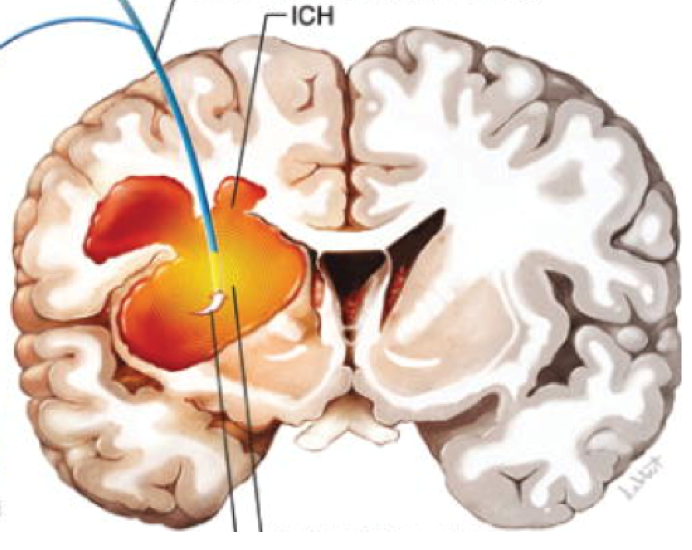

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), a subtype of stroke, is a devastating condition whereby a hematoma is formed within the brain parenchyma with or without blood extension into the ventricles. Non-traumatic ICH comprises 10-15% of all strokes and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.

ICH risk factors include chronic hypertension, amyloid angiopathy, anticoagulation (medication), and vascular malformations. The resultant brain injury is often classified as primary, this being the initial damage to the parenchyma by the blood clot, secondary, or the damage caused by complications from intracranial blood.

Management of ICH ranges from medical therapy to open surgery to actively evacuate the hematoma, with studies still being held to find less invasive therapies to improve prognosis.

Etiology

Non-traumatic Intracerebral hemorrhage can be divided into primary and secondary, where primary bleeds account for 85% of all ICH and are related to chronic hypertension or amyloid angiopathy. Secondary hemorrhage is considered to be related but not limited to bleeding diathesis (iatrogenic, congenital, acquired), vascular malformations, neoplasms, hemorrhagic conversion of an ischemic stroke, and drug abuse.

Primary or spontaneous ICH accounts for over 85% of hemorrhagic strokes. A primary ICH diagnosis is often one of exclusion where no other pathological or structural cause is found and is supported by a history of chronic hypertension, increased age, and location of the clot. Over 60% of primary bleeds are related to hypertension, and these hematomas are most commonly seen in the posterior fossa, pons, basal ganglia, and thalamus. Lobar hemorrhages in older patients are often the distinguishing feature of amyloid angiopathy.

Epidemiology

The incidence of stroke, both ischemic and hemorrhagic, in 2010 was approximately 33 million worldwide, with hemorrhagic strokes accounting for nearly a third of cases and over half of all the deaths. Though the worldwide incidence sits at nearly 20 cases per 100,000 people every year, the occurrence of ICH in low/middle-income regions is double compared to the rates in more economically developed countries. Fortunately, however, the mortality from such strokes has decreased worldwide. The increased risk in lower-economically developed countries is potentially related to the lack of education regarding primary prevention and inadequate access to medical care.

Stroke, both ischemic and hemorrhagic, ranks fourth in the list of the leading cause of death in the United States, with just under 20% of cerebrovascular incidents in the United States are ICHs.

Pathophysiology

Hemorrhages within cerebral parenchyma are often categorized into primary injury, i.e., the immediate tissue injury from the hematoma and secondary injury – the subsequent pathological change that results from the hemorrhage. Although ICH is commonly considered a single event disease, it is more recently being considered as a dynamic condition with multiple phases, these being:

- The initial extravasation of blood into the parenchyma

- Subsequent bleeding around the clot causing expansion

- Swelling or edema around the hematoma

An acute ICH causes a sudden increase in mass within the parenchyma of the brain, which causes compression and disruption of the surrounding neuronal tissue, leading to a potential compromise of the nearby cell signaling pathways and causing a focal neurological deficit. Blood dissipates within white-matter, leaving small focuses of intact neural tissue amongst the hematoma and around it, which is, in theory, salvageable.

When the hematoma is within the brainstem, the initial manifestation can be a decreased level of consciousness, along with cardiorespiratory distress or even arrest. One important factor in predicting patients’ prognosis and functional outcome is the expansion of the initial hematoma, which is defined on repeat CT scanning as a volume increase of 33 to 50%. Clot expansion of this volume is seen in just under 40% of patients and is related to increased morbidity and poorer outcomes.

History and Physical

As with all acute presentations, a concise but thorough history is crucial to forming a diagnosis. Relevant details in the history of ICH include the chronicity of symptoms and the time of ictus. Most commonly, vascular events are sudden and may be precipitated by high energy activities such as exercise or heavy lifting or using drugs like cocaine and alcohol. A significant smoking history has implications in vascular disease such as hypertension and vasculitis, which both are risk factors for ICH.

The most common feature of ICH is a sudden onset focal neurological deficit, which is determined by the location of the hemorrhage and subsequent edema. This is often associated with a decrease in the patients’ conscious level, measured using the Glasgow coma scale (GCS). Other common symptoms and signs include headache, nausea/vomiting, seizures (both convulsive and non-convulsive), and a raised diastolic blood pressure (>110 mmHg). Extension of the clot into the ventricles can cause obstructive hydrocephalus, which manifests itself with signs and symptoms of raised intracranial pressure, including postural headaches (worse on lying flat), papilledema, nausea, vomiting, diplopia, confusion, and a reduced conscious level.

Initial evaluation of the patient should include checking for airway patency and appropriate ventilation. Circulation must be assessed next, and one must secure wide bore venous access and aim for systolic blood pressure targets between 120 to 140 mmHg to maintain cerebral perfusion. A very low consciousness level (GCS<8) must be treated as an emergency, and obtaining a secure airway in a patient with a low conscious level is a priority. The patient must then have a complete peripheral inspection and examination- this includes checking the patients’ pupils as dilation and inactivity of the pupils is a sign of cerebral herniation and must be treated immediately.

Once medically stable, it is pertinent to confirm a clear history of anticoagulant/ antiplatelet therapy or coagulation disorders and check the patients’ clotting function and other routine blood tests. Any coagulation abnormalities should be discussed with hematologists and corrected appropriately.

Treatment / Management

In the prehospital setting, the mainstay of treatment involves airway, breathing, and circulatory support, aiming to get the patient to the closest emergency department (with capabilities of managing stroke). A detailed history from any witnesses or family/carers at the site of the incident is always useful as it may provide pertinent information regarding trauma, medical, and drug history.

Most ICH presentations include raised blood pressure for various physiological reasons, including pain, stress, a history of increased blood pressure, and raised ICP. The potential consequence of a persistently raised systolic blood pressure is hematoma expansion, and therefore initial medical management must include treatment of elevated blood pressure. However, blood pressure reduction should take into account the patients’ regular blood pressure, as a hypertensive patient may not be able to maintain cerebral perfusion at a significantly lower SBP.

Differential Diagnosis

Many pathologies can present themselves acutely with symptoms and signs similar to that of acute ICH. The common symptoms of headache and nausea along with clinical manifestations of decreased consciousness, confusion, seizures, and focal neurological deficit are often seen with other intracranial hemorrhages, such as a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and a subdural hemorrhage (both acute and chronic), neoplasms (primary and secondary), and infection.

Brain tumors frequently present insidiously. Due to their gradual growth, most patients can compensate until the intracranial pressure is high enough to produce symptoms of headache, nausea, vomiting, seizures, and decreased GCS. On closer examination of the history, there is often evidence of a subtle progressive history, and contrasted CT imaging is often required to make a diagnosis. Patients with neoplastic lesions may present with hemorrhages into a primary or secondary brain tumor in some situations. This can cause diagnostic uncertainty that often requires delayed imaging, in the form of MR, to make a more accurate diagnosis of underlying pathology.

Prognosis

Acute ICH can be a catastrophic event with the mortality largely predicted by the hematoma size, location, and the patients’ GCS on admission. At 30 days, the mortality rate can be as high as 50%, with most of these deaths occurring within 24 hours of the initial insult, with intraventricular blood and hydrocephalus often playing a large part in the patient’s deterioration. Patients presenting to the hospital with a GCS <9 and a clot size of 60 ml or more have a nearly 90% mortality rate. Posterior fossa and brainstem hemorrhages carry a poorer prognosis due to the propensity for the development of obstructive hydrocephalus and life-sustaining function, respectively. Less than 20% of patients that survive are seen to be autonomous at 6 months following the acute hemorrhage. Further, factors such as the patients’ age and comorbidities also affect outcomes following ICH.

Although there are no definitive ways of predicting outcomes, early withdrawal of care can, in itself, lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy. Therefore full medical care and treatment should be offered to all patients with acute ICH who do not have an advance directive or known wishes for the first 24 to 48 hours post ictus.