Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Published (updated: ).

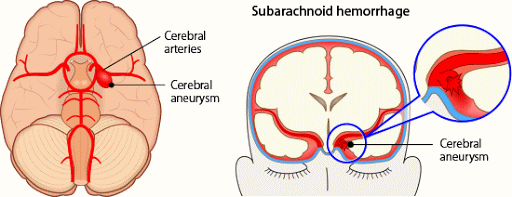

Overall, about 20% of strokes are hemorrhagic, with SAH and Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) each accounting for 10%. Subarachnoid space is described as a space between the arachnoid membrane and the pia mater. It consists of the cerebrospinal fluid and the blood vessels that supply different areas of the brain. A subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is defined as the accumulation of blood in the space between the arachnoid membrane and the pia mater around the brain referred to as the subarachnoid space. The etiology of SAH can be either nontraumatic (about 85% are secondary to aneurysm rupture) or traumatic in nature. Most nontraumatic causes of SAH (~ 85%) are caused by the rupture of an intracranial aneurysm. The remaining 15-20% of patients presenting with SAH do not have a vascular lesion on the initial digital subtraction angiography. Regardless of the cause, a SAH is often a devastating clinical event with substantial mortality and high morbidity among survivors. Prehospital care is critical and involves triaging the patient with attention to the airway, breathing, and circulation to a hospital with neurocritical/neurosurgical expertise. The classic presentation is often a sudden-onset, severe headache typically described as the “worst headache of my life”. Treatments are based on randomized controlled studies and prospective cohort studies. A SAH has a prolonged course of illness and is complicated by various factors not limited to seizures, vasospasm, hydrocephalus, and delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI).

History and Physical

A typical presenting symptom is a thunderclap headache. Patients usually describe it as the “worst headache of my life.” This problem should prompt further imaging. A headache is frequently associated with nausea, vomiting (often projectile), nuchal rigidity, and photophobia. Meningismus (a group of symptoms similar to meningitis such as stiff neck, reaction to light and headache without inflammation of the membranes lining the brain) is typically present due to blood extending into the fourth ventricle. As the blood moves further down the spinal cord, it irritates surrounding nerves causing neck pain and stiffness. Practitioners should perform a detailed exam. The presence of a focal deficit increases the grade of subarachnoid hemorrhage and changes the perspective of post-event recovery. Patients with a high-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage often present in a state of coma that calls for an urgent evaluation and treatment, as in some the coma can be reversible.

Several grading scales are used in clinical practice to standardize the classification of patients with aSAH and to monitor progression and change in condition. These scales are based on the initial clinical neurological examination and the appearance of blood on the initial head CT. These scales include the Glasgow Coma Scale,

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), introduced in 1974, is designed as a reliable and objective scale of neurological function in three subscales of level of consciousness, eye-opening, and motor function. The scale ranges from 3 to 15, and points are denoted based on the level of response. A higher score correlates to a better patient’s neurological condition. The GCS is commonly used for the initial and ongoing assessment of a patient with possible or confirmed brain injury. It is used to determine neurological deficits and their changes over time.

Prognosis

SAH is associated with a high early mortality rate. A population-based study published in 2017 found that approximately 18 percent of patients with SAH died suddenly before being evaluated in a hospital. Among patients who reach the hospital alive, much of the subsequent early mortality is caused by the common complications of aneurysmal SAH related to initial bleeding, rebleeding, vasospasm and delayed cerebral ischemia, hydrocephalus, increased intracranial pressure, seizures, and cardiac complications.

Long-term complications of SAH include neurocognitive dysfunction, epilepsy, and other focal neurologic deficits. In one registry, more than 10 percent of patients with SAH remained moderately or severely disabled.

Complications

- Seizures

- Vasospasm

- Rebleed

- Hydrocephalus

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Brain herniation

- Cerebral infarction

- Medical complications

- Neurogenic pulmonary edema

- Death