Subdural Hematoma

Published (updated: ).

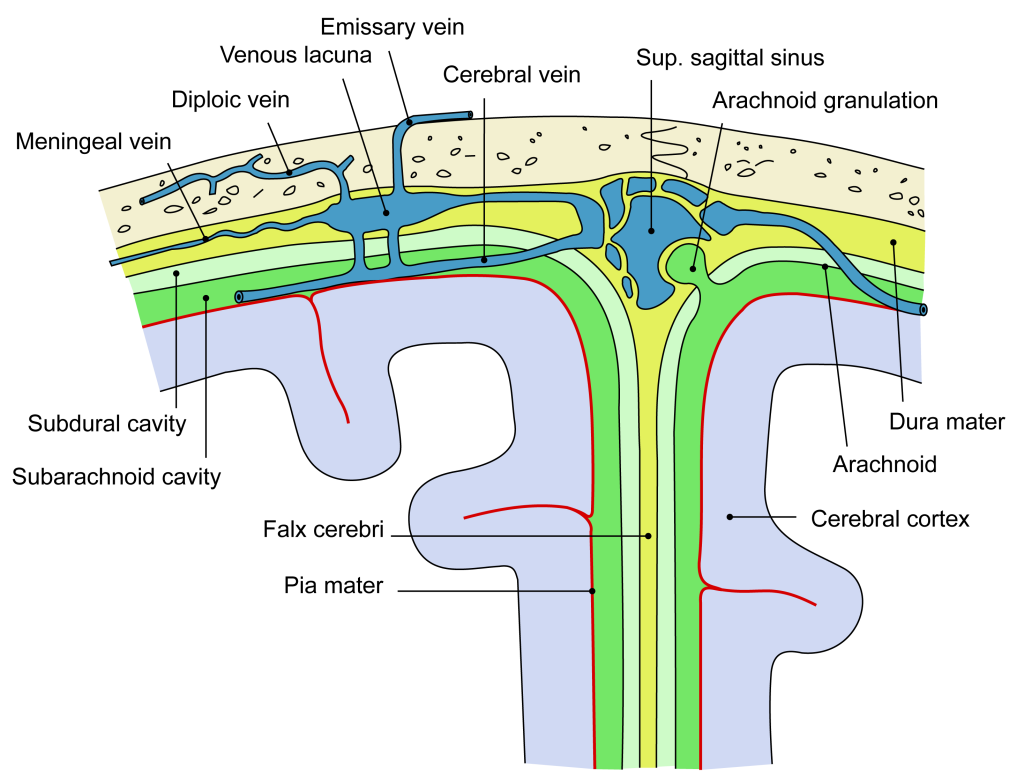

A subdural hematoma forms because of an accumulation of blood under the dura mater, one of the protective layers to the brain tissue under the calvarium. The understanding of subdural hematoma relies on the knowledge of neuroanatomical sheets covering the brain. The brain is the central repository of delicate neural tissue. This network of neurons and neuronal connective tissue is prone to injury without the protective layers, starting with the scalp and the bony structures of the skull. The brain finds its protection under the skull by the meninges that comprise three layers.

The inner surface of the skull toward the brain includes:

First, there is a leather-like structure called the dura mater, derived from the neural crest, adhering to the periosteum and facing the other meningeal structure, the arachnoid mater. The arachnoid mater lies under the dura mater (middle meningeal layer) forming many villi piercing through the dura with bridging veins acting as one-way valves to drain the neural tissue lying underneath the last meningeal layer called the pia mater. These so-called bridging veins may rupture when direct opposing forces rupture their thin walls, releasing blood under the dura mater forming a subdural hematoma.

When there is a larger space between the dura mater and the brain, as seen in the young, growing brain or an aging brain (because of contraction), the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flows between bridging veins occupying a larger space. In this context, the structure stretches bridging veins and renders them prone to rupture. A small extravasation may resolve spontaneously. A larger bleed may augment the distance between the bridging veins and trigger an extensive amount of blood layering around the brain, slowly augmenting subdural space, decreasing the space of the brain leading to herniation of the cerebral structures.

Etiology

In the pediatric patient, trauma is the most common cause of subdural hematoma. Contributing factors include blunt and shearing injuries. Cranium extraction device use and traumatic birth delivery accounts for a majority of the SDH in the newborn period. However, after the newborn period until age 2 years, the cause of SDH is predominantly due to accidental injury or intentional head injury. SDH due to intentional injury is frequently referred to as “shaken baby syndrome” The term correlates with the back-and-forth motion of the brain in the skull, held by the fragile bridging veins that rupture after violent, repeated movements against the inertia of the brain. Infants are prone to this as they do not have the muscular strength of the neck muscles to sustain the head during such an event. This also leads to retinal bleeding, a pathognomonic sign of shaken baby syndrome.

Pathophysiology

In shaken baby syndrome or battered infant syndrome, the acceleration and decelerating forces of the brain during violent shaking of the head causes the brain to move in an opposite direction to the meninges causing the bridging veins to rupture and bleed in the subdural space. This potential space may accumulate a significant quantity of blood in various stages to exist in an acute or sub-acute form. Often, the bleeding is undetected initially, discovered as a chronic subdural hematoma. When there is a sufficient accumulation of blood to occupy a large intracranial space, the brain midline shifts toward the opposite side, encroaching on the brain structures against the inner surface of the calvarium after decreasing the volume of the lateral third and fourth ventricles. As the intracranial space becomes limited, the volumetric forces push the uncal portion of the temporal lobe toward the foramen magnum causing herniation of the brain.

Treatment / Management

The immediate treatment of a subdural hematoma initially includes management of the airway, breathing with stabilization of the circulation for the critical care professional. After stabilization and monitoring of the patient, a secondary plan of care should follow. The management must include the involvement of neurosurgery and neurological consultation with a consensus on the injury and a determination of the immediate and long-term consequences. Conservative non-surgical management for subacute and chronic subdural hematomas is appropriate if the accumulation has not extended further into the calvarium as to cause impingement on the brain or the brain stem. In contrast, a subdural hematoma that is quickly increasing or causing any signs of increased intracranial pressure, for example, hypertension, bradycardia with erratic respirations should prompt surgical evacuation and is paramount to preserve vital functions. In the interim, the clinician must begin immediate medical management. These measures include sedation, neuromuscular blockade when appropriate, moderate hyperventilation to a Pc02 (32 to 36), adequate oxygenation to maintain Sp02 greater than 95%, head elevation, and avoidance of hyperthermia. The infusion of hypertonic saline or mannitol serves to decrease the intracranial pressure by promoting osmotic changes in the brain and transiently affecting the rheologic properties of the cerebral blood flow, respectively.

Differential Diagnosis

Other fluid substances may collect within the layers of the meninges to give the appearance of a subdural hematoma. A careful history and evaluation of radiological findings are necessary to rule out Purulent accumulation in the subdural abscess. In certain cases, the subarachnoid space occupied by the normally-occurring cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with a natively decreased brain mass as in hydrocephalus ex vacuo may give the appearance of a subdural hematoma.

Prognosis

The prognosis of children affected by subdural hematoma is widely variable and depends on the extent of the intracranial injury. Many cases of subdural hematoma either traumatic or abusive remain undetected. However, many children live with severe neurological deficits including seizures, neurodevelopmental delay with static encephalopathy because of severe, devastating neurological injury.