Concussion

Published (updated: ).

A concussion is a “traumatically induced transient disturbance of brain function.” Concussions are a subset of the neurologic injuries known as traumatic brain injuries. Traumatic brain injuries have varying severity, ranging from mild, transient symptoms to extended periods of altered consciousness. Given the usually self-limited nature of symptoms associated with a concussion, the term mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) is often used interchangeably to refer to a concussion. However, concussions are technically a subset of mTBIs. Prognosis is usually good, and most patients experience complete resolution of symptoms.

Etiology

A concussion occurs as a result of either a direct or indirect injury to the head. Providers often consider a direct, traumatic blow to the head as a significant cause of a concussion. However, indirect traumatic forces elsewhere in the body can lead to an acute acceleration/deceleration injury to the brain, which can also lead to a concussion.

Epidemiology

In the United States, each year, there are an estimated 1.7 million traumatic brain injuries that prompt presentation to the emergency department. The Center for Disease Control also estimates that when accounting for outpatient visits for TBIs and patients not seeking care for injuries, the actual incidence may range from 1.4 to 3.8 million concussions per year. Frequent causes of concussions are motor vehicle crashes, being struck by an object, assault, and participation in recreational athletics. Although sports-related concussions make up a small percentage of overall concussions, much of the current research surrounding concussions stems from data on sports-related head injuries. Football consistently accounts for the highest number and percentage of athletics-related concussions in high school and college athletes. At the same time, soccer is responsible for the highest percentage of concussions in female athletes. Female athletes suffer concussions about twice as often as male participants in the same sport.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiologic mechanism of a concussion is complex. The acute symptoms of a concussion are due primarily to a “functional disturbance rather than structural injury.” “Neurochemical and neurometabolic events” after an injury to the head result in an alteration of neurologic function. Acceleration, deceleration, or rotation of the head result in acute axonal injury via disruption of neurofilament organization. The release of electrolytes through ion channel depolarization leads to a release of neurotransmitters and subsequent neurologic dysfunction. Changes to glucose metabolism decreased cerebral blood flow, and mitochondrial dysfunction also occurs.

History and Physical

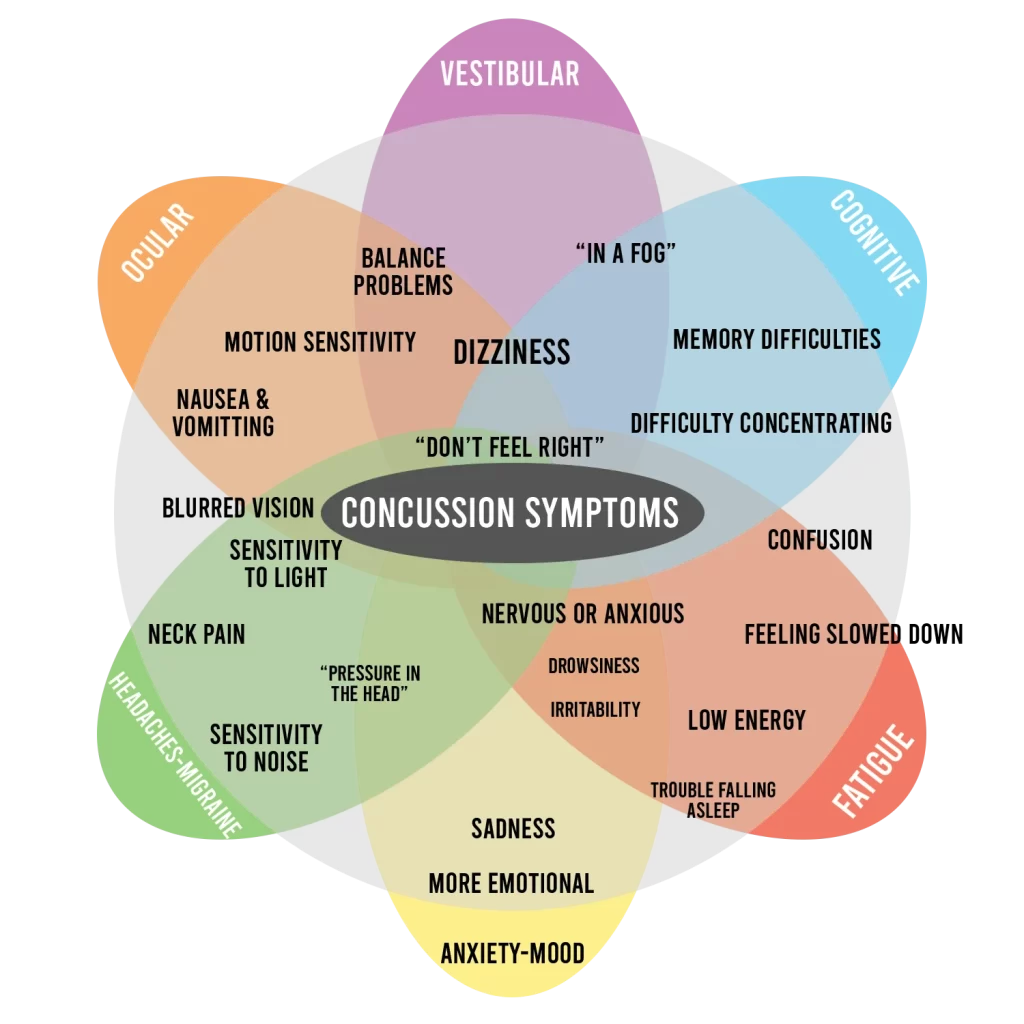

Assessment of a patient with a possible concussion should include gathering information on the mechanism of injury, the symptoms the patient is experiencing, the timing of symptom onset, and the severity and persistence of symptoms. The symptoms of a concussion can be wide-ranging but often fall into one of four main domains, which are listed below. Some of the most common symptoms seen with concussion within each domain include:

1. Affective/emotional function

- Irritability

- Changes in mood

2. Cognitive function

- Confusion/disorientation

- Amnesia

- Mental fogginess

- Difficulty concentrating

3. Physical/somatic symptoms

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Difficulties with balance

- Visual changes

4. Sleep

- Drowsiness

- Sleeping less than usual

- Sleeping more than usual

- Difficulty falling asleep

Treatment / Management

After diagnosing a concussion, an outpatient observation by a responsible individual educated on warning signs requiring further evaluation is generally appropriate. Patients with concerning signs or symptoms for more severe head injury may require continued hospital observation. Diagnosis of a concussion should prompt removing a patient from an environment that may lead to a repeat blow to the head (i.e., immediate removal of an athlete from athletic participation).

Treatment of a concussion is primarily supportive. Supportive care of concussion centers around the initial limitation of physical and cognitive activity, followed by a gradual return to previous activity levels. There is no longer a role for extended, strict cognitive and physical rest. While reasonable to encourage rest during the acute post-injury period (i.e., the initial 24 to 48 hours), the patient should then undergo a gradual return to activity. However, there is no known optimal amount of time for the initial rest period. The patient should proceed with a stepwise return to activity with careful monitoring for the return or worsening of symptoms. Recurrence of symptoms warrants a reduction in activity level until symptoms improve. Each increase in activity should generally take at least 24 hours, but again there is no definitive evidence for the optimal timing of a return-to-activity protocol. An athlete diagnosed with a concussion should be forbidden to return to play until cleared by a medical provider.

There is emerging evidence that early, targeted therapies and interventions aimed at specific clinical profiles of a concussion may be beneficial; however, evidence for identifying these clinical profiles and the efficacy of the therapy is still preliminary. Examples of these interventions include vision training for patients with oculomotor dysfunction or cognitive-behavioral therapy for mood disturbances.

Over-the-counter analgesics aimed at controlling headache symptoms are an option, although there is limited evidence as to their efficacy. However, other medications that may alter a patient’s cognitive function, sleep patterns, or mood are not advisable as they may mask symptoms of a concussion. Preventive headache medications should not be initiated after a concussion but can be resumed if the patient was on them before an injury.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis immediately after a head injury should include potentially severe injuries, including cervical spine injury, intracranial hemorrhage, or skull fracture. The differential diagnosis for post-concussive symptoms shifts once outside of the window of the acute injury. Symptoms of a concussion can overlap with other potentially pre-existing chronic conditions such as:

- Headache disorders or migraines

- Mental health diagnoses such as anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder

- Problems with attention such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- Sleep dysfunction

Complications

The most commonly seen complication of a concussion is a post-concussion syndrome (PCS) characterized by persistent symptoms lasting weeks to months after the initial injury. The median duration of symptoms in one study was seven months. The transition from a concussion to the post-concussion syndrome is “ill-defined and poorly understood.” Any of the possible concussion symptoms can be present with post-concussion syndrome, but PCS characteristically presents with multiple “somatic, emotional, and cognitive symptoms.” The severity of the initial injury does not seem to correlate with the likelihood of developing the post-concussion syndrome. Still, a history of prior concussions does appear to correlate with the likelihood of the development of PCS.

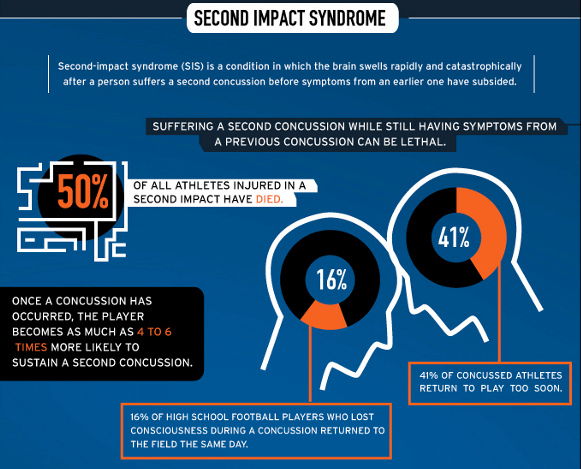

One of the most feared and concerning complications of a concussion, although rare, is a second-impact syndrome. Second-impact syndrome (SIS) involves a repeat blow or injury to the head before the complete resolution of the initial concussion, resulting in usually rapid, severe swelling of the brain. SIS has the potential for dangerous neurologic complications, including brain herniation and death, though much of the existing data and research on the condition is anecdotal.