Basilar Skull Fracture

Published .

Basilar skull fractures, usually caused by substantial blunt force trauma, involve at least one of the bones that compose the base of the skull. Basilar skull fractures most commonly involve the temporal bones but may involve the occipital, sphenoid, ethmoid, and the orbital plate of the frontal bone as well. Several clinical exam findings highly predictive of basilar skull fractures include hemotympanum, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) otorrhea or rhinorrhea, Battle sign (retroauricular or mastoid ecchymosis), and raccoon eyes (periorbital ecchymosis). Basilar skull fractures are commonly associated with facial fractures, cervical spine injury, intracranial hemorrhage, cranial nerve injury, vascular injury, and meningitis.

Basilar skull fractures are most commonly seen in younger people due to their propensity to do high-risk activities. The majority of basilar skull fractures are managed with conservative care.

Etiology

Most basilar skull fractures are caused by high-velocity blunt trauma such as motor vehicle collisions, motorcycle crashes, and pedestrian injuries. Falls and assaults are also important causes. Penetrating injuries such as gunshot wounds account for less than 10% of cases.

Epidemiology

Basilar skull fractures are relatively uncommon and are present in about 4% of all patients with a severe head injury. They represent 19% to 21% of skull fractures.

Pathophysiology

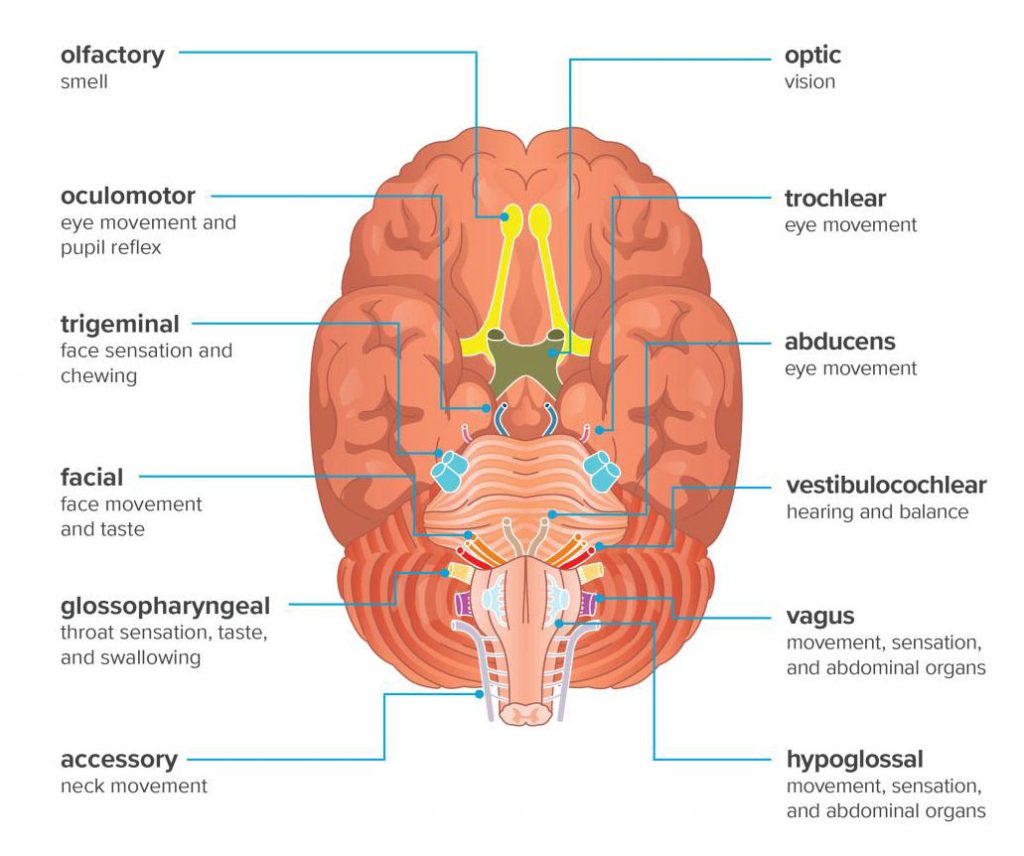

The location of the fracture is predictive of associated injuries:

- Temporal fractures, which are most common, are associated with carotid injury, injury to cranial nerves VII or VIII, and mastoid cerebrospinal fluid leak.

- Anterior skull base fractures are associated with orbital injury, nasal cerebrospinal fluid leak, and injury to cranial nerve I.

- Central skull base fractures are associated with injury to cranial nerves III, IV, V or VI, and carotid injury.

- Posterior skull-based fractures are associated with a cervical spine injury, vertebral artery injury, and injury to the lower cranial nerves. These injuries are very serious and often the patients have hemiplegia or paraplegia

Basilar skull fractures are often associated with other central nervous systems (CNS) pathologies like epidural hematoma due to the weakness of the temporal bone and the close proximity of the middle meningeal artery. At least 50% of basilar skull fractures are associated with another CNS injury and about 10% have cervical spine fracture. The majority of basilar skull fractures involve the petrous bone, the external auditory canal, and tympanic membrane.

History and Physical

Clinical features of basilar skull fractures vary depending on the degree of the associated brain and cranial nerve injury.

Patients may present with altered mental status, nausea, and vomiting. Oculomotor deficits due to injuries to cranial nerves III, IV, and VI may be present. Patients may also present with facial droop due to compression or injury to cranial nerve VII. Hearing loss or tinnitus suggests damage to cranial nerve VIII.

Several clinical signs highly predictive of a basilar skull fracture include:

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea or otorrhea: “Halo” sign is the double ring pattern described when bloody fluid from the ear or nose containing CSF is dripped onto paper or linen. This sign is based on the principle of chromatography; components of a liquid mixture will separate when traveling through a material. This sign is not specific to the presence of CSF, as saline, tears or other liquids will also produce a ring pattern when mixed with blood. CSF leaks may be delayed hours to days after the initial trauma.

- Periorbital ecchymosis (raccoon eyes): Pooling of blood surrounding the eyes is most commonly associated with fractures of the anterior cranial fossa. This finding is typically not present during the initial evaluation and is delayed by 1 to 3 days. If bilateral, this finding is highly predictive of a basilar skull fracture.

- Retroauricular or mastoid ecchymosis (Battle sign): Pooled blood behind the ears in the mastoid region is associated with fractures to the middle cranial fossa. Like Raccoon eyes, this finding is frequently delayed by 1 to 3 days.

- Middle ear injury is seen in nearly one-third of patients and may present with hemotympanum, disruption of the ossicles, hearing loss, and even CSF leak.

- Other features include dizziness, tinnitus, and nystagmus

The presence of Battle sign and raccoon eye are highly predictive of basilar skull fracture.

Treatment / Management

Basilar skull fractures are usually due to significant trauma. A thorough trauma evaluation with interventions to stabilize airway, ventilation, and circulatory issues is the priority. Associated cervical spine injury is common, so attention to cervical spine immobilization, particularly during airway management is necessary. Nasogastric tubes and nasotracheal intubation should be avoided because of the risk for inadvertent intracranial tube placement.

Patients with basilar skull fractures require admission for observation. Those taking anticoagulants should be admitted to a facility with immediate neurosurgical capabilities and the ability to do frequent assessments of the neurologic decline, even if no hemorrhage is present on initial imaging. Patients with intracranial hemorrhage require emergent neurosurgical evaluation. Otherwise, skull base fractures are often managed expectantly. Surgical management is necessary for cases complicated by intracranial bleeding requiring decompression, vascular injury, significant cranial nerve injury, or persistent cerebrospinal fluid leak.

Basilar skull fractures increase the risk of meningitis because of the increased possibility of bacteria from the paranasal sinuses, nasopharynx, and the ear canal making direct contact with the central nervous system. Patients with associated cerebrospinal fluid leaks, present in up to 45% of patients with basilar skull fractures, are often treated with prophylactic antibiotics to prevent meningitis, but there is no good evidence to support this practice.

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis includes congenital maldevelopment of the skull bones and basal encephaloceles which can present with CSF leak.

Prognosis

The prognosis of skull base fractures depends on:

- The associated dural tear and CSF leak

- Instability

- Associated injuries

- Initial severity of neurologic and vascular injuries

The majority of CSF leaks resolve spontaneously within 5-10 days but some can persist for months. Meningitis may occur in less than 5% of patients but the risk increases with the duration of the CSF leak.

Conductive hearing loss usually resolves within 7-21 days.

Complications

- CSF leak

- Meningitis

- Cranial nerve palsies

- Hearing loss

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis

- Vertigo

- Intracranial hemorrhage

- Death

Cranial nerve deficits involve loss of smell and facial palsy.

Basilar skull fractures can also be associated with a vascular injury resulting in occlusion, fistula formation, bleeding, or pseudoaneurysm formation.