Flail Chest

Published .

Introduction

Flail chest is a traumatic condition of the thorax. It may occur when 3 or more ribs are broken in at least 2 places. It is considered a clinical diagnosis as everybody with this fracture pattern does not develop a flail chest. A flail chest arises when these injuries cause a segment of the chest wall to move independently of the rest of the chest wall. A flail chest can create a significant disturbance to respiratory physiology. This disturbance in respiratory function is important in patients who are older or who have chronic lung disease. Flail chest is an important injury with significant complications. A flail chest is usually associated with significant blunt chest wall trauma. It often occurs in the setting of other injuries and is an extremely painful condition. Both factors significantly contribute to the difficulty in managing this condition. Flail chest is often unilateral but can be bilateral. It may be suspected based on radiographic findings but is diagnosed clinically.

Etiology

Because this is a traumatic disorder, risk factors for flail chest include the risk factors for major trauma. Male sex and intoxication being independent risk factors. Motor vehicle collisions are the cause of 75% of the major trauma which results in flail chest. Falls particularly in the elderly cause another 15%. Certain traumatic events like direct blows to the chest are more likely to cause 2 fractures on a given rib. Rollover and crush injuries more commonly break ribs at only one point and thus do not, as often, cause flail chest. In childhood metabolic bone disease and osteogenesis imperfecta predispose to this condition. The elderly are predisposed to flail chest both because they have an age-related physiologic stiffening of the chest wall and because they may have osteoporosis. Because they are also more likely to have pre-existing lung disease they are also at the highest risk for the complications of flail chest.

Epidemiology

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma gives trauma statistics for the US. 1% of the US population/year will experience a significant traumatic event. Chest trauma occurs in 20% of major trauma and is responsible for 25% of traumatic deaths. Flail chest occurs in about 7% of chest trauma. Flail chest patients usually require hospitalization. Flail chest occurs in isolation in less than 40% of cases. More often it is accompanied by pulmonary contusions, hemo/pneumothorax, head injury, and occasionally major vascular injury. The mortality of flail chest ranges from 10% to 20% but is often due to accompanying injury rather than the flail chest alone. Morbidity is high due to long and complicated hospital stays and recovery.

Pathophysiology

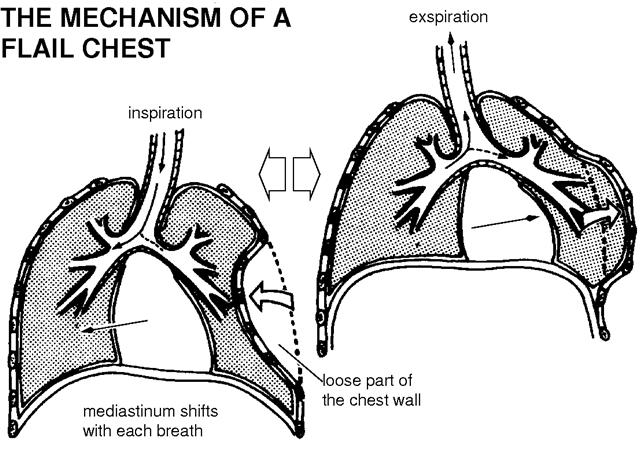

The movement of air in and out of the lungs is dependent on changes in intrathoracic pressure. Inspiration relies on the coordinated function of respiratory muscle groups including the diaphragm, external intercostal, parasternal internal intercostal, and accessory muscles. The descent of the diaphragmatic dome increases in the vertical dimension of the chest cavity and creates negative pressure. The diaphragm alone can maintain adequate ventilation at rest. The intercostals play an increasingly important role in inspiration during exercise and in pathologic states. Exhalation is usually passive due to the elastic recoil of the lung, but the abdominal muscles and the intercostals may participate. With a flail chest, the continuity of the chest wall is disrupted, and the physiologic action of the ribs is altered. The motion of the flail segment is paradoxical to the rest of the chest. It is paradoxical because the flail segment moves inward while the rest of the chest wall moves outward. The severity of this paradoxical motion and the physiological effect is determined by three factors; pleural pressure, the extent of the flail, and the activation of intercostals muscles during inspiration.

A flail segment of the chest wall will negatively affect respiration in three ways: ineffective ventilation, pulmonary contusion, and hypoventilation with atelectasis. There is ineffective ventilation because of increased dead space, decreased intrathoracic pressure, and increased oxygen demand from injured tissue. Pulmonary contusion in adjacent lung tissue is almost universal with flail chest. Pulmonary contusion leads to edema, hemorrhage and may eventually have some element of necrosis. Pulmonary contusion impairs gas exchange and decreases compliance. Hypoventilation and atelectasis result from the pain of the injury. The pain causes splinting which decreases the tidal volume and predisposes to the formation of atelectasis.

History and Physical

The history may be obvious as most of the flail chests will be in the setting of major blunt force trauma. The elderly are at increased risk. The diagnosis may be more cryptogenic in cases of abuse. nonverbal patients, cases of abuse, or when history can not be obtained.

The physical exam should be the exam performed in all patients with potential thoracic trauma. Fully expose the patient. Obtain a full set of vitals including an accurate measure of respiratory rate and oxygen saturation. The patient usually complains of severe chest wall pain and may have tachypnea and splinting or manifest respiratory insufficiency.

Specifically, observe the chest for paradoxical wall motion. In inspiration, the flail segment will go in while the rest of the chest expands and in expiration, the flail segment will be pushed out while the rest of the chest contracts. Of note, the absence of observable paradoxical motion does not exclude this disease and it may become more apparent as the intercostals become fatigued.

Because of the pressure changes with positive pressure ventilation, patients on BiPAP or those who are mechanically intubated do not exhibit paradoxical chest wall motion. Thus, in the mechanically ventilated trauma patient, the diagnosis of flail chest may be delayed.

Treatment / Management

Management of a flail chest should include these areas of concern; maintaining adequate ventilation, fluid management, pain management, and management of the unstable chest wall. Ventilation should be maintained with oxygen and non-invasive ventilation when possible. Invasive mechanical ventilation is used only when other methods fail and extubation should be attempted as early as possible.

The judicious use of fluid is recommended in most trauma settings and is important in the flail chest because of the almost ubiquitous lung contusion.

Pain management should be addressed early and aggressively. This may include nerve blocks or epidural anesthesia. There should also be a focus on excellent pulmonary toilet and steroids should be avoided.

Internal pneumatic stabilization has been used successfully to treat complicated cases. Surgical stabilization may be considered in patients who are getting a thoracotomy for other reasons, in those who fail to wean off a ventilator, and in those whose respiratory status continues to decline despite other treatments. Surgery essentially uses metallic wires to stabilize the ends of the fractured rib. There are many other fixation devices available on the market, including mesh.

Prognosis

In general, patients who do not require mechanical ventilation have a much better prognosis than those who do. However, adverse effects are very common leading to a high rate of disability. The pain may last months or even years in some patients.