Cardiac Tamponade

Published (updated: ).

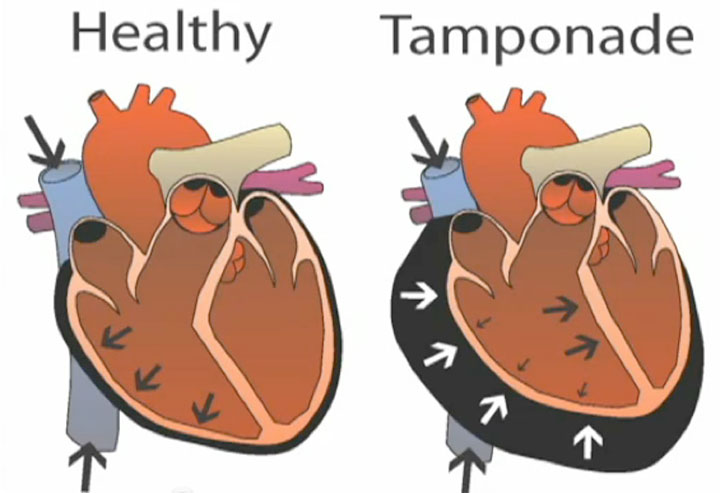

Cardiac tamponade is a medical or traumatic emergency that happens when enough fluid accumulates in the pericardial sac compressing the heart and leading to a decrease in cardiac output and shock. The diagnosis of cardiac tamponade is a clinical diagnosis that requires prompt recognition and treatment to prevent cardiovascular collapse and cardiac arrest. The treatment of cardiac tamponade can be performed at the bedside or in the operating room

Etiology

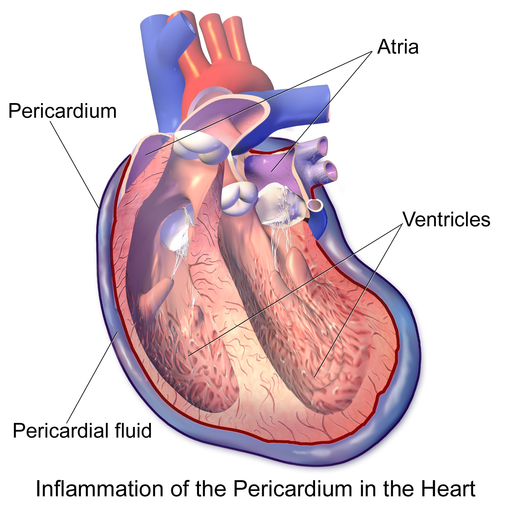

Cardiac tamponade is caused by the buildup of pericardial fluid (exudate, transudate, or blood) that can accumulate for several reasons. Hemorrhage, such as from a penetrating wound to the heart or ventricular wall rupture after an MI, can lead to a rapid increase in pericardial volume. Other risk factors, which tend to produce a slower-growing effusion, include infection (tuberculosis [TB], myocarditis), autoimmune diseases, neoplasms, uremia, and other inflammatory diseases (pericarditis). The pericardial fluid that builds up slowly is better tolerated in patients than with rapid accumulations. Hence, traumatic causes (hemopericardium) require small volumes to causes hemodynamic instability versus pericardial effusions from medical causes such as malignancy where large volumes of fluid may accumulate in pericardial sac before patients become symptomatic.

Epidemiology

The incidence or prevalence of pericardial effusions in the overall population is unknown. However, there are sub-groups of patients with a higher incidence of pericardial effusions. These include HIV-positive patients, patients with end-stage renal disease, those with known or occult malignancies, a history of congestive heart failure, tuberculosis, autoimmune diseases like lupus, or penetrating traumatic injury to central chest “cardiac box.”

Pathophysiology

Normally, a small, physiologic amount of fluid surrounds the heart within the pericardium. When the volume of fluid builds up fast enough, the chambers of the heart are compressed, and tamponade physiology develops rapidly with much smaller volumes. The classical example is the traumatic cardiac injury resulting in hemp-pericardium. Under this pressure, the chambers of the heart are unable to relax leading to decreased venous return, filling and cardiac output.

Slow growing effusions, such as those due to autoimmune disease or neoplasms, allow for stretching of the pericardium, and effusions can become quite large before leading to tamponade physiology.

The fluid may be hemorrhagic, serosanguineous or chylous. The underlying pathology behind cardiac tamponade is a decreased in diastolic filling, which leads to a decreased cardiac output. One of the first compensatory signs is tachycardia to overcome the reduced output. In addition, the compression also limits systemic venous return, impairing filling of the right atrium and ventricle.

History and Physical

Patients with cardiac tamponade present similar to patients with other forms of cardiogenic or obstructive shock. They may endorse vague symptoms of chest pain, palpitations, shortness of breath, or in more severe cases, dizziness, syncope, and altered mental status. They may also present in a pulseless electrical activity cardiac arrest. The classic physical findings in cardiac tamponade included in Beck’s triad are hypotension, jugular venous distension, and muffled heart sounds. Pulsus paradoxus, which is a decrease in systolic blood pressure by more than 10 mm Hg with inspiration is an important physical exam finding that suggests a pericardial effusion is causing cardiac tamponade.

Pulsus paradoxus may be absent in patients with ASD, elevated diastolic pressures, pulmonary hypertension and aortic regurgitation.

Kussmaul’s sign is a paradoxical rise in jugular venous pressure resulting in jugular vein distention on inspiration is sometimes seen in cardiac tamponade.

In patients with large pericardial effusions, the Ewart sign may be present. This is an area of dullness with bronchial breath sounds heard just below the left scapula.

When fluid compresses the heart and impairs filling, the interventricular septum bows toward the left ventricle during inspiration due to increased venous return to the right side of the heart. This further decreases the pressure of the left ventricle leading to decreased left ventricular preload and stroke volume. The challenge with making the diagnosis of tamponade with clinical signs alone is difficult since they are neither sensitive nor specific.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of cardiac tamponade can be suspected on history and physical exam findings. ECG may be helpful, especially if it shows low voltages or electrical alternans, which is the classic ECG finding in cardiac tamponade due to the swinging of the heart within the pericardium that is filled with fluid. This is a rare ECG finding, and most commonly the ECG finding of cardiac tamponade is sinus tachycardia. In severe cases, one may note electrical alternans.

A chest x-ray may show an enlarged heart and may strongly suggest pericardial effusion if a prior chest radiograph with a normal cardiac silhouette is available for comparison. CT chest can also pick up pericardial effusion.

Echocardiography is the best imaging modality to use at the bedside, whether it is a point-of-care echo or a cardiology echo study. Echocardiography can not only confirm there is a pericardial effusion, but determine its size, and whether it is causing compromise of cardiac function (right ventricular diastolic collapse, right atrial systolic collapse).

Treatment / Management

Before rushing to decompression of the pericardium, the patient should be provided with oxygen, volume expansion and bed rest with legs elevated. If possible, positive pressure mechanical ventilation should be avoided as it may further decrease venous return and aggravate the symptoms.

The treatment of cardiac tamponade is the removal of pericardial fluid to help relieve the pressure surrounding the heart. This can be done by performing a needle pericardiocentesis at the bedside, performed either using traditional landmark technique in a sub-xiphoid window or using a point-of-care echo to guide needle placement in real-time. Often the removal of the first small amounts of fluid can make a large improvement in hemodynamics, but leaving a catheter within the pericardium can allow for further drainage.

Surgical options include creating a pericardial window or removing the pericardium. Emergency department resuscitative thoracotomy and the opening of the pericardial sac is a therapy that can be used in traumatic arrests with suspected or confirmed cardiac tamponade. These options are preferable to needle pericardiocentesis for traumatic pericardial effusions.

Volume resuscitation and pressor support may be helpful; however, these are temporizing measures that should be performed while preparing for definitive treatment with one of the above procedures.

Prognosis

Cardiac tamponade is a medical emergency and without treatment is invariably fatal. The key is the timing of intervention; the longer the delay, the worse the outcomes. Patients with tamponade caused by malignant disease have death rates exceeding 75% within 12 months.