Hemothorax

Published (updated: ).

Introduction

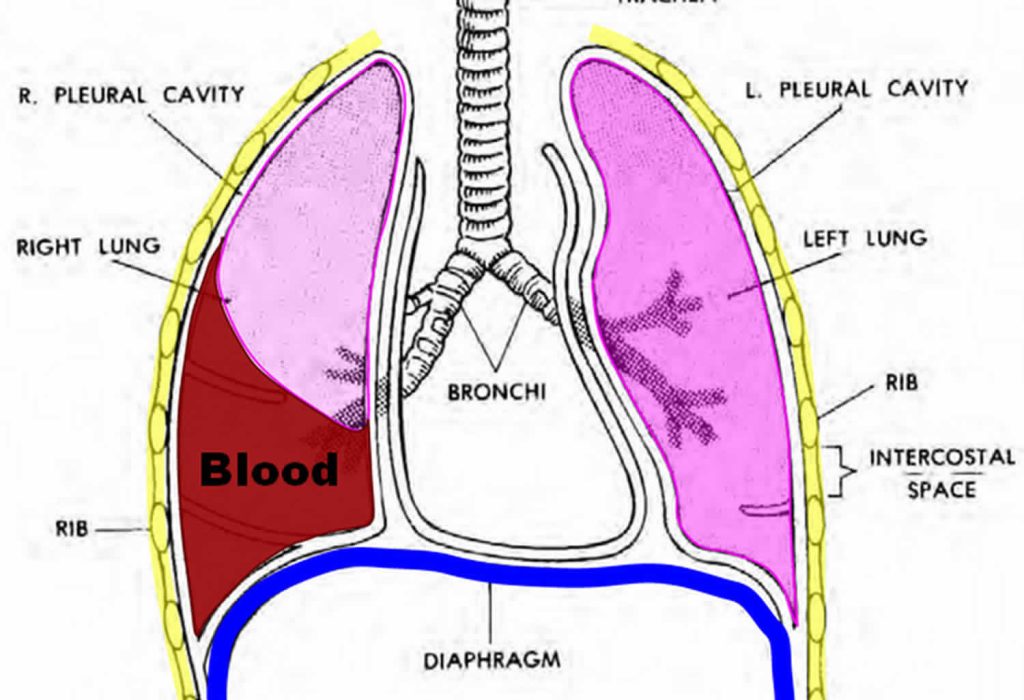

Hemothorax is a frequent consequence of traumatic thoracic injuries. It is a collection of blood in the pleural space, a potential space between the visceral and parietal pleura. The most common mechanism of trauma is a blunt or penetrating injury to intrathoracic or extrathoracic structures that result in bleeding into the thorax. Bleeding may arise from the chest wall, intercostal or internal mammary arteries, great vessels, mediastinum, myocardium, lung parenchyma, diaphragm, or abdomen.

Etiology

Hemothorax is a frequent manifestation of traumatic injury (blunt or penetrating) to thoracic structures. Most cases of hemothorax arise from blunt mechanism with an overall mortality of 9.4%. Non-traumatic causes are less common. Examples include iatrogenic, lung sequestration, vascular, neoplasia, coagulopathies, and infectious processes.

Pathophysiology

Bleeding into the hemithorax may arise from diaphragmatic, mediastinal, pulmonary, pleural, chest wall and abdominal injuries. Each hemithorax can hold 40% of a patient’s circulating blood volume. Studies have shown that injury to intercostal vessels (e.g., internal mammary arteries and pulmonary vessels) lead to significant bleeding requiring invasive management. Early physiologic response of a hemothorax has hemodynamic and respiratory components. The severity of the pathophysiologic response depends on the location of the injury, the patient’s functional reserve, the volume of blood, and the rate of accumulation in the hemithorax. In the early response, acute hypovolemia leads to a decrease in preload, left ventricular dysfunction and a decrease in cardiac output. Blood in the pleural space affects the functional vital capacity of the lung by creating alveolar hypoventilation, V/Q mismatch, and anatomic shunting. A large hemothorax can lead to an increase in hydrostatic pressure which exerts pressure in the vena cava and pulmonary parenchyma causing impairment in preload and increase pulmonary vascular resistance. These mechanisms result in tension hemothorax physiology and cause hemodynamic instability, cardiovascular collapse, and death.

History and Physical

Thorough and accurate gathering of history from the patient, witnesses, or prehospital providers helps determine those patients that are at low vs. high risk of intrathoracic injury. Important history components include chest pain, dyspnea, mechanism of injury (fall, direction, and speed), drug/alcohol use, comorbidities, surgical history, and anticoagulation/antiplatelet therapies. The mechanisms of action that were predictive of significant thoracic injury are motor vehicle accident greater than 35 mph, fall from more than 15 feet, pedestrian ejection of more than 10 feet, and trauma with depressed level of consciousness.

Clinical findings of hemothorax are broad and may overlap with pneumothorax; these include respiratory distress, tachypnea, decreased or absent breath sounds, dullness to percussion, chest wall asymmetry, tracheal deviation, hypoxia, narrow pulse pressure, and hypotension. Inspect the chest wall for signs of contusion, abrasions, “seat belt sign,” penetrating injury, paradoxical movement (“flail chest”), ecchymosis, deformities, crepitus, and point tenderness. Distended neck veins are concerning for pneumothorax or pericardial tamponade but might be absent in the setting of hypovolemia. Increased respiratory rate, effort, and use of accessory muscles may be signs of impending respiratory failure.

The following physical findings should prompt the clinician to consider these conditions:

- Distended neck veins → pericardial tamponade, tension pneumothorax, cardiogenic failure, air embolism

- “Seat belt sign” → deceleration or vascular injury; chest wall contusion/abrasion

- Paradoxical chest wall movement → flail chest

- Facial/neck swelling or cyanosis → superior mediastinum injury with occlusion or compression of superior vena cava (SVC)

- Subcutaneous emphysema → torn bronchus or lung parenchyma laceration

- Scaphoid abdomen → diaphragmatic injury with herniation of abdominal content into the chest

- Excessive abdominal movement with breathing → chest wall injury