How Shock Patients Die: Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

Published (updated: ).

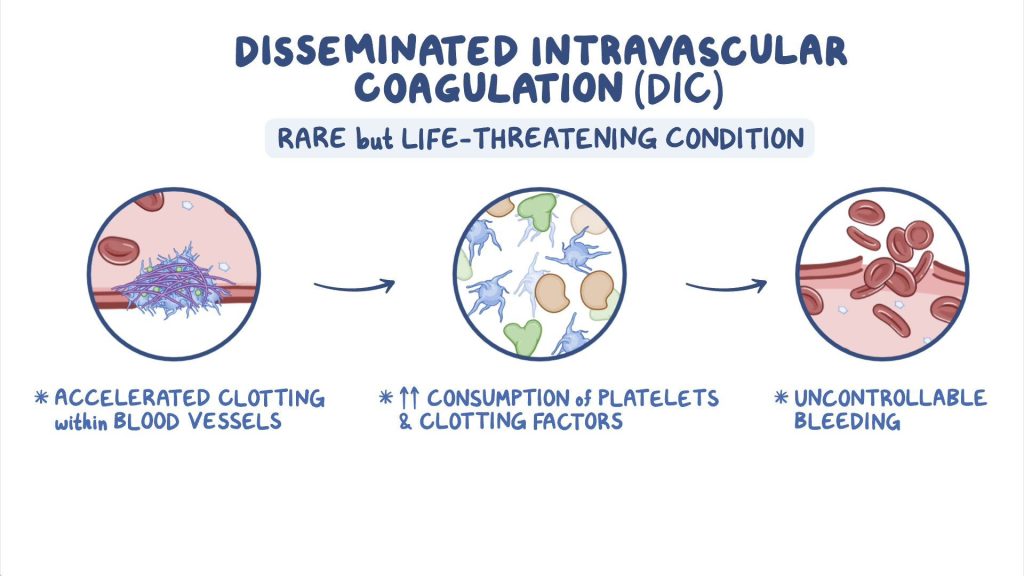

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) can be defined as a widespread hypercoagulable state that can lead to both microvascular and macrovascular clotting and compromised blood flow, ultimately resulting in multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. As this process begins consuming clotting factors and platelets in a positive feedback loop, hemorrhage can ensue, which may be the presenting symptom of a patient with DIC. Disseminated intravascular coagulation typically occurs as an acute complication in patients with underlying life-threatening illnesses such as severe sepsis, hematologic malignancies, severe trauma, or placental abruption. Determining the consequences of DIC and the overall mortality rate of DIC remains difficult as patients with this condition also have additional diagnoses that can cause many of the signs and symptoms consistent with DIC, particularly if they are also suffering from acute or chronic liver failure. While concomitant disease states can obscure a patient’s prognosis, mortality rates have been shown to double in septic patients or those with severe trauma if they are also suffering from DIC.

Etiology

Multiple medical conditions can lead to the development of disseminated intravascular coagulation either through a systemic inflammatory response or the release of procoagulants into the bloodstream. The pathological process of DIC has been estimated to occur in up to 30% to 50% of cases of severe sepsis, which is the most common cause of DIC. Classically, DIC has been associated with gram-negative bacteria sepsis, though the prevalence of this disorder in sepsis due to gram-positive organisms may, in fact, be similar. Other causes of sepsis, including parasites, can also lead to DIC. Up to 20% of patients with metastasized adenocarcinoma or lymphoproliferative disease also suffer from DIC in addition to one to five percent of patients with chronic diseases like solid tumors and aortic aneurysms. Obstetrical complications such as placental abruption, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP syndrome), and amniotic fluid embolism have also been known to lead to DIC. Other causes of DIC include trauma, pancreatitis, malignancy, snake bites, liver disease, transplant rejection, and transfusion reactions. About 15.5% of cases of DIC have also been linked to complications occurring after surgery.

Pathophysiology

Also referred to as consumptive coagulopathy, DIC involves the homeostatic imbalance between coagulation and bleeding. Tissue factor (TF), which may be released into the circulation from vascular endothelial damage from trauma or certain cancer treatments, bacterial endotoxins, or cytokine exposure, activates coagulation factor VII to VIIa in the coagulation pathway. Via the extrinsic pathway, thrombin and fibrin are formed and result in the formation of clots in the circulation. As this process continues, thrombin and fibrin further impair the coagulation cascade through positive feedback loop stimulation and coagulation inhibitor consumption. Clotting factors, as a result, are consumed due to clotting, which can lead to excessive bleeding. Platelets also may become trapped and consumed in this process.

History and Physical

Components of a patient’s history that may be consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulation include a recent history of severe infections or trauma as well as hepatic failure, obstetric complications, and malignancy. A remote history of deep vein or arterial thromboses may also be suggestive of DIC. Patients may experience bleeding from multiple sites including gingiva, areas of trauma or surgery, the vagina, the rectum, or through devices such as urinary catheters. Symptoms such as hematuria, oliguria, and anuria may be seen if concomitant renal failure from DIC results. Likewise, end-organ damage to the lungs may lead to dyspnea and hemoptysis if pulmonary hemorrhage or pulmonary embolism is occurring and a patient may have mental status change if either thrombi or hemorrhage to areas of the brain arise. A patient could also experience chest pain if arterial occlusion of a coronary artery develops. Regarding signs of DIC on physical exam, obvious bleeding, or frank hemorrhage in various areas of the body may be noted. Skin lesions including ecchymosis, hematomas, jaundice from liver failure, necrosis, and gangrene may also arise. Excessive coagulation may lead to widespread purpura, petechiae, and cyanosis. A patient in DIC may also experience acute respiratory failure or neurological deficits based on the location of bleeding or clots.

Evaluation

No single history, physical exam, or laboratory component can lead to a diagnosis of or rule out DIC; therefore, a combination of both subjective, objective, and laboratory findings should be utilized to make a diagnosis of DIC. Laboratory findings suggestive of DIC include both an increased prothrombin time (PT) and an increased partial thromboplastin time (PTT), as well as a decreased fibrinogen level as widespread activation and consumption of the clotting cascade occurs.

Treatment / Management

The treatment for DIC centers on addressing the underlying disorder, which ultimately led to this condition. Consequently, therapies such as antibiotics for severe sepsis, possible delivery for placental abruption, and possible exploratory surgical intervention for trauma represent the mainstays of treatment for DIC. Platelet and plasma transfusions should only be considered in patients with active bleeding or a high risk of bleeding or those patients requiring an invasive procedure.

Pearls and Other Issues

Disseminated intravascular coagulation can quickly lead to multi-organ failure and death, particularly if early recognition and treatment fail to occur. A high index of suspicion of this high mortality disease in critically ill patients remains paramount to improve outcomes in patients with DIC.