Septic Shock

Published .

Sepsis syndromes span a clinical continuum with variable prognoses. Septic shock, the most severe complication of sepsis, carries high mortality. In response to an inciting agent, pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory arms of the immune system are activated in concert with the activation of monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils that interact with the endothelium through pathogen recognition receptors to elaborate cytokines, proteases, kinins, reactive oxygen species, and nitric oxide. As the primary site of this response, the endothelium not only suffers microvascular injury but also activates the coagulation and complement cascades which further exacerbate vascular injury, leading to capillary leak. This cascade of events is responsible for the clinical signs and symptoms of sepsis and progression from sepsis to septic shock. The ability to balance pro-inflammatory responses to eradicate the invading microorganism with anti-inflammatory signals set to control the overall inflammatory cascade ultimately determines the degree of morbidity and/or mortality suffered by the patient. Judicious and early antimicrobial administration, sepsis care bundle use, and early goal-directed therapies have significantly and positively impacted sepsis-related mortality. However, early identification remains the best therapeutic tool for sepsis treatment and management.

Etiology

Risk factors that predispose to sepsis include:

- Diabetes

- Malignancy

- Chronic kidney and liver disease

- Use of corticosteroids

- Immunosuppressed state

- Burns

- Major surgery

- Trauma

- Presence of indwelling catheters

- Prolonged hospitalization

- Hemodialysis

- Extremes of age

Epidemiology

Annually, the rate of this debilitating condition is rising by almost 9%. The incidence of sepsis and severe sepsis have risen over the past decade from approximately 600,000 to over 1,000,000 hospitalizations per year from 2000 through 2008. Accompanying this trend has been a rise in healthcare expenditure, making sepsis the most expensive healthcare condition in 2009, accounting for 5% of total United States hospital costs. The case fatality for patients with sepsis has been declining due to advances in sepsis management provided by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign.

Pathophysiology

Sepsis is a clinical state that falls along a continuum of pathophysiologic states, starting with a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and ending in multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (MODS) before death.

The earliest signs of inflammation are heralded by the following:

- Fever (temperature higher than 38 C or hypothermia (temperature less than 36 C)

- Tachycardia (heart rate more than 90 beats per minute),

- Tachypnea (respiratory rate more than 20 breaths per minute)

The presence of two of these four clinical signs is necessary for the diagnosis of systemic inflammatory response syndrome. After that, systemic inflammatory response syndrome with an infectious source suffices the clinical definition for sepsis.

With the development of hypotension, tissue demands are not adequately met by tissue oxygenation, and the patient is now defined to be in severe sepsis. The decline in peripheral vascular perfusion and oxygenation leads to cellular and metabolic derangements, most notably a shift from aerobic respiration to anaerobic respiration with ensuing lactic acidosis. Tissue hypoperfusion may also be manifested by signs of end-organ damage, such as pre-renal azotemia or transaminitis. The difference in oxygen supply and demand can be monitored during resuscitation by trending the mixed venous oxygen saturation from a central line in the superior vena cava (SVC), when available.

When sepsis-induced hypotension remains refractory to initial management with fluid resuscitation, septic shock ensues. Septic shock is distinguished from other shock states as a distributive type of shock. The action of a combination of inflammatory mediators (histamine, serotonin, super-radicals, lysosomal enzymes) elaborated in response to bacterial endotoxins leads to a marked increase in capillary permeability and a concomitant reduction in peripheral vascular resistance. This translates not only into a reduction in afterload but also in preload from a decline in venous return from third-spacing. The resulting reduction in stroke volume is accommodated initially by an elevation in heart rate, i.e., compensated septic shock. As a result, the patient is in a hyperdynamic state that is characteristic of septic shock.

Clinically, patients, have a dynamic precordium with tachycardia and bounding peripheral pulses. They are warm to the touch and have a reduction in capillary refill (flash cap refill). This is described as warm shock. As shock progresses, elevated catecholamine production leads to an increase in peripheral vascular resistance as the body attempts to shunt blood away from non-vital tissues (gastrointestinal (GI) tract, kidneys, muscle, and skin) to the vital tissues (brain and heart). This is described as cold shock. Understanding the pathophysiology and continuum of septic shock is imperative in initiating appropriate treatment measures.

Functionally, septic shock is defined by persistent hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation from 60 ml/kg to 80 mL/kg of either crystalloid or colloid fluid. At this point, the initiation of appropriate vasoactive medications such as beta-adrenergic or alpha-adrenergic drugs is of utmost importance. The progression of organ dysfunction despite high-dose vasoactive administration defines the state of multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) which carries mortality as high as 75%. While the exact circumstances predicting poor prognosis and death have been difficult to determine, immunologic dissonance (exaggerated pro-inflammatory response) versus immunologic paralysis (exaggerated anti-inflammatory response) have been purported to play a role.

History and Physical

Early Signs and Symptoms

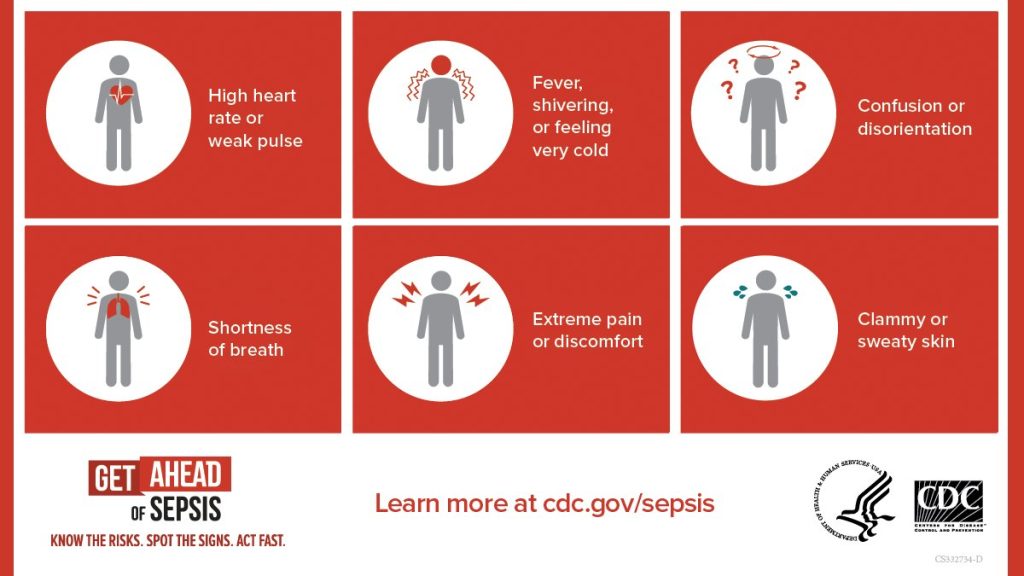

Sepsis is defined as systemic inflammatory response syndrome plus an infectious source. Therefore, earlier on in the presentation of sepsis, patients present with the following vital sign changes:

- Fever, temperature higher than 38 C, or hypothermia, temperature lower than 36 C

- Tachycardia with a heart rate higher than 90 beats per minute in adult patients or less than two standard deviations for age in pediatric patients

- Tachypnea with respiratory rate greater than 20 breaths per minute in adult patients or more than two standard deviations for age in pediatric patients

Signs and Symptoms of Severe Sepsis Severe sepsis is defined as sepsis and end-organ dysfunction. At this stage, signs, and symptoms may include:

- Altered mental status

- Oliguria or anuria

- Hypoxia

- Cyanosis

- Ileus

Patients progressing to septic shock will experience signs and symptoms of severe sepsis with hypotension. Of note, at an early “compensated” stage of shock, blood pressure may be maintained, and other signs of distributive shock might be present, for example, warm extremities, flash capillary refill (less than one second), and bounding pulses, also known as warm shock. This stage of shock, if managed aggressively with fluid resuscitation and vasoactive support, can be reversed. With the progression of septic shock into the uncompensated stage, hypotension ensues, and patients may present with cool extremities, delayed capillary refill (more than three seconds), and thready pulses, also known as cold shock. After that, with continued tissue hypoperfusion, shock may be irreversible, progressive rapidly into multiorgan dysfunction syndrome and death.

Prognosis

Septic shock is a serious illness and despite all the advances in medicine, it still carries high mortality which can exceed 40%. Mortality does depend on many factors including the type of organism, antibiotic sensitivity, number of organs affected and patient age. The more factors that match SIRS, the higher the mortality. Data suggest that tachypnea and altered mental status are excellent predictors of poor outcomes. Finally, prolonged use of inotropes to maintain blood pressure is also associated with adverse outcomes. Even those who survive are left with significant functional and cognitive deficits.

Complications

- ARDS

- Acute/chronic renal injury

- DIC

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Acute liver failure

- Myocardial dysfunction

- Multiple organ failure