Opiate Overdose

Published (updated: ).

Introduction

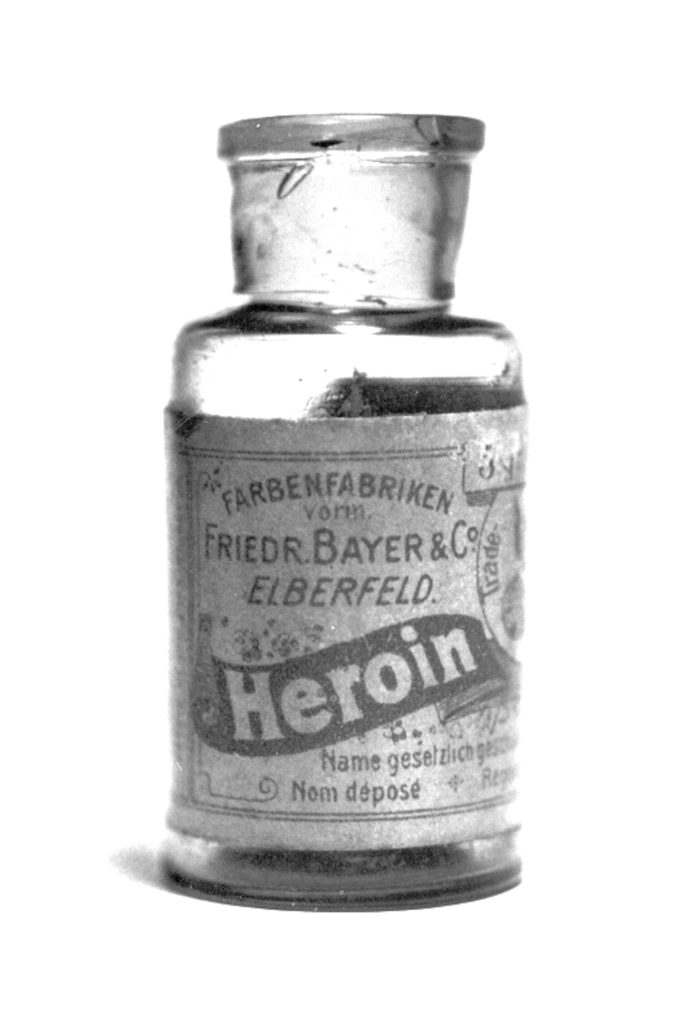

One very common reason why patients seek medical care is for pain. Today, there are many ways to relieve pain, and one of them is with the use of opiates. Opiates have formally been approved for analgesia for close to 70 years, and for the most part, these drugs have been assumed to be relatively safe. However, in the last 2 decades, many reports have raised concern about the safety of these drugs. Cases of overdose and opiate toxicity are continually reported in all major cities in the United States. More notable is that the prescriptions for opiates have dramatically increased over the past 2 decades. This empirical prescription habit by healthcare workers has also led to an epidemic of an overdose outside the healthcare setting. Thus, for practicing healthcare workers, it is important to be aware of opiate toxicity in patients who are lethargic or unresponsive for no apparent reason.

Opioid overdose occurs when a person has excessive unopposed stimulation of the opiate pathway. This can lead to decreased respiratory effort and possibly death. The frequency of opioid overdose is rapidly increasing. Drug overdose is the leading cause of accidental death in the United States, with opioids being the most common drug. The CDC currently estimates more than 1000 emergency department visits daily related to the misuse of opioids and about 91 opioid overdose deaths every day.

Prescriptions for opioid-containing medications quadrupled between 1999 and 2010. This paralleled a four-fold increase in overdose deaths due to opioids. The majority of the opioid deaths are attributable to the use of heroin and synthetic opiates other than methadone.

The issue with poorly treated pain has led medical professionals to use all types of short and long-acting opiates, and while this has made a difference in relieving pain, some patients often do not remain compliant with proper dosing. When the patient increases the dose or duration of opioids, then toxicity is a potential complication. Although annual rates of transition are low, this is commonly caused by individuals transitioning from the nonmedical use of prescription opioids to heroin.

Adulterants: On the street, the majority of illicit drugs available are often contaminated with other substances. Sometimes to increase profits, sellers often add other agents to the formula without telling the end user. In many cases, these additives are pharmacologically active. Two decades ago in New York city, heroin had been adulterated with scopolamine, and this resulted in severe anticholinergic toxicity. Similarly, adulteration of cocaine is very common.

Prescription Monitoring

Most states have established prescription drug monitoring programs to counter the liberal prescription of opiates by healthcare workers (PDMP). In fact, in Kentucky, healthcare professionals must first consult with the state’s online drug database to determine which analgesic drug can be prescribed to patients. Such state enacted legislation has been developed to stop mass opiate prescription by healthcare workers. In addition, this also helps prevent diversion of legitimate opiate prescriptions .

Also, with the help of the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), there are now statewide registries of controlled substances that can assist healthcare providers to track usage patterns among patients in an effort to identify those individuals at high risk for opiate diversion or abuse. Even though the ready availability of opiates does play a role in opiate addiction, so far so no one has shown that there is a direct link between opiate abuse and legitimate use of these drugs for pain.

Etiology

Causes of opioid overdose can include:

- Complications of substance abuse

- Unintentional overdose

- Intentional overdose

- Therapeutic drug error

Risk of opioid overdose increases in the following:

- Those that take escalating doses

- Return to use after cessation

- Those with severe medical and psychiatric conditions such as depression, HIV, and lung/liver disease

- Those that combine opioids and sedative medications

- Male gender

- Younger age (20 to 40 years)

- White non-Hispanic race

More than 1.5 million emergency department visits are related to opioid analgesics. Opioids are a common cause of death due to overdose.

Pathophysiology

An opiate is derived from the opium poppy plant, while opioids are substances that act on the opiate receptors. Opioids work via the endogenous opioid system by acting as a potent agonist to the mu receptor. This results in a complex cascade of intracellular signals resulting in dopamine release, blockade of pain signals, and a resulting sensation of euphoria. Opioid receptors are located in the brain, spinal cord, and gut. In overdose, there is an excessive effect on the portion of the brain regulating respiratory rate, resulting in respiratory depression and eventually death. The typical symptoms seen in overdose are pinpoint pupils, respiratory depression, and a decreased level of consciousness. This is known as the “opioid overdose triad.”

Opioids may be agonists, partial agonists, or agonist-antagonists of opioid receptors. The currently available opiates lower the perception of pain and in some case decrease the pain stimulus. There are several types of opiate receptors in the central and peripheral nervous system. When these receptors are stimulated, it results in the suppression of the sensation of pain. However, not all opiate receptors have the same analgesic potency when stimulated. Opioids reduce pain perception by inhibition of synaptic neurotransmission and binding of opioid receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems.

Tolerance occurs rapidly with opioids. With overdose, patients often succumb to respiratory failure. Tolerance to loss of the hypercarbic drive takes longer to develop than other euphoric effects, but opioid-tolerant patients do not develop complete tolerance to loss of hypoxic stimulus. This leaves them susceptible to death from overdose.

History and Physical

Since the majority of patients overdosed on opiates are lethargic or comatose, the history is usually obtained from family, friends, bystanders, and emergency medical service providers. On many occasions at the scene, one may find pills, empty bottles, needles, syringes and other drug paraphernalia. Other features that one should try and obtain in the history are the amount of drug ingested, any congestion, and time of ingestion. In the prehospital setting, sometimes EMS personnel may administer naloxone, which may help make the diagnosis of opiate overdose.

Physical Examination

Universally, patients with opiate overdose may be lethargic or have a depressed level of consciousness. Opiate overdose will also cause respiratory depression, generalized central nervous system (CNS) depression, and miosis. However, it is important for all healthcare workers to be aware that miosis is not universally present in all patients with opiate overdose and there are many other causes of respiratory depression. Other features of opiate overdose include euphoria, drowsiness, change in mental status, fresh needle marks, seizures and conjunctival injections.

Skin

Examination of the extremities may reveal needle track marks if intravenous opiates are abused. Morphine and heroin are also injected subcutaneously by many addicts. In some cases, the opium oil may be inhaled, and the individual may also have patch marks on the body from the use of fentanyl. Most opiates can cause the release of histamine which can result in itching, flushed skin, and urticaria.

Pulmonary

In some cases of morphine toxicity, the respiratory distress and hypoxia may, in fact, present with pupillary dilatation. In addition, drugs like meperidine, morphine, propoxyphene and diphenoxylate/atropine are known to cause midpoint pupils or frank mydriasis. The breathing is usually impaired in patients with a morphine overdose. One may observe shallow breathing, hypopnea, and bradypnea. The respiration rate may be 4 to 6 breaths per minute and shallow. Since opiates can also cause bronchoconstriction, some individuals may present with dyspnea, wheezing and frothy sputum.

Cardiovascular

Most opiates are known to cause peripheral vasodilatation, which can result in moderate to severe hypotension. However, this hypotension is easily reversed with changes in body position or fluid administration. If the hypotension is severe and is unresponsive to fluids, then one must consider other contestants.

Gastrointestinal

Both nausea and vomiting are also seen in patients with opiate toxicity;. The reason is that opiates can cause gastric aperistalsis and slow down the intestine motility.

Psychiatric Features

Even though opiates are generalized CNS depressants, they can cause the following neuropsychiatric symptoms:

- Anxiety

- Agitation

- Depression

- Dysphoria

- Hallucinations

- Nightmares

- Paranoia

Neurological

Opiates do have the ability to lower the threshold for seizures, and generalized seizures can occur, especially in young children. This is primarily due to paradoxical excitation of the brain. In adults with seizures, the 2 opiates most likely involved are propoxyphene or meperidine. In rare cases, hearing loss may be noted especially in individuals who have consumed alcohol with heroin. However, this auditory deficit is reversible.

Treatment / Management

Management at the Scene

The care of the patient at the scene depends on the vital signs. If the patient is comatosed and in respiratory distress, airway control must be obtained before doing anything else. Endotracheal intubation is highly recommended for all patients who unable to protect their airways. If there is suspicion of opiate overdose, then naloxone should be administered to reverse the respiratory depression. However, one should be aware that naloxone can also cause agitation and aggression when it reverses the opiate. If the individual is a drug abuser, the lowest dose of naloxone to reverse respiratory apnea should be administered. In the ambulance, the patient may become combative or violent, and use of restraints may be an option. If the individual has no intravenous access, one may administer the naloxone intramuscularly, intranasally, intraosseous or via the endotracheal tube. Data show that the intranasal route is as effective as the intramuscular route in the prehospital setting.

Emergency Department Care

When a patient presents to the emergency department with any type of drug overdose, the ABCDE protocol has to be followed. In some cases, airway control has been obtained by emergency medical personnel at the scene, but if there is any sign of respiratory distress or failure to protect the airways in an un-intubated patient with a morphine overdose, one should not hesitate to intubate. Next, if there is any suspicion of occult trauma to the cervical spine, immobilization should be a priority. In most emergency rooms, patients who present with an unknown cause of lethargy or loss of consciousness have their blood glucose levels drawn.

Initial treatment of overdose begins with supportive care. This includes assistance in respiration, CPR if no spontaneous circulation is occurring, and removal of the opioid agent if a patch or infusion are delivering it. If the physician suspects that the individual has overdosed on an opiate and has signs of respiratory and CNS depression, no time should be wasted on laboratory studies; instead, naloxone should be administered as soon as possible.

Naloxone is a competitive antagonist of the opiate receptor. It can be administered by intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intranasal routes. Additionally, it can be used in an off-label manner by administering it via endotracheal tube or in a nebulized form, though research on the efficacy of tracheal absorption has only been performed on animal models.

Naloxone

Naloxone is a pure competitive antagonist of opiate receptors and has no agonistic activity. The drug is relatively safe and can be administered intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous or via the endotracheal tube. Recently the FDA approved of an intranasal formula which is showing promise especially in patients who do not have intravenous access.

Whether naloxone is administered via the endotracheal tube or intravenously the onset of action is within minutes. A second dose can be administered every 2 to 3 minutes. With subcutaneous or intramuscular injection, the onset may be delayed for 3 to 10 minutes. As soon the patient is alert and awake, the dose of naloxone should be disconnected. For patients overdosed on diphenoxylate, methadone, butorphanol, nalbuphine and pentazocine, higher doses of naloxone are required.

Starting Dose of Naloxone

In some patients with opiate overdose and long-term drug addicts, peripheral intravenous access can be difficult and in such cases, the naloxone can be administered intramuscularly or intranasally (2 mg). Even with this route, there is a reversal of opiate toxicity within 5 to 10 minutes. The recently available intranasal formula releases 0.4 mg per single dose spray and may have to be repeatedly given.

The half-life of naloxone is about 30 to 45 minutes with a duration of action between 90 to 180 minutes. The variations exist because of the route of administration and dose. In a patient with no prior opiate use or history of drug abuse, naloxone can be administered via an intravenous infusion without fear of inducing withdrawal symptoms, but the patient’s pain may quickly return, and one must have alternative ways to manage the pain. Naloxone infusion is usually administered in D5W or isotonic saline and is necessary to manage overdose caused by long action opiates like methadone.

In patients who have taken large doses of propoxyphene, methadone, diphenoxylate/atropine or fentanyl, much larger doses of naloxone are usually required to reverse the toxicity. Repeat doses of 2 mg may be required every 3 to 4 minutes to a total of 10 mg. If the patient fails to respond to a total of 10 mg of naloxone, the diagnosis of opiate toxicity should be reconsidered. Many of the street opiate preparations are adulterated with contaminants, and the response to naloxone is not always complete. If the patient remains in respiratory distress, one must be prepared to intubate the patient.

Role of Activated Charcoal

If the patient is alert at the time of admission, activated charcoal can be used to decontaminate the gastrointestinal tract in patients with opiate overdose. While normally activated charcoal usually has to be administered within 1 hour of ingestion of a drug to be effective, with opiates, there is slowing of gastric motility, and hence, activated charcoal can be given as late as 2 to 3 hours after ingestion. As long as there are no contraindications, activated charcoal should be administered to all symptomatic patients with opiate overdose. If the patient is not alert, then airway protection is necessary; if activated charcoal enters the airways, the result can be catastrophic. In some patients, orogastric lavage may help.

Other Measures

There are some patients with opiate toxicity who may fail to respond to high dose naloxone treatment. If the cause is determined to be an opiate and the patient appears to be in respiratory arrest, anecdotal reports indicate that buprenorphine may be useful.

Intranasal Administration

While naloxone is very effective if given promptly, its use has long been limited to administration by physicians and paramedics. With the increase in opioid overdoses, there has been a push to allow intranasal medication administration by bystanders. Evidence looking at the efficacy of out of hospital naloxone administration is promising. The bioavailability of a concentrated naloxone nasal spray was shown to be about 25%. Fifty percent absorption occurs within 6 to 8 minutes, and maximum blood concentration is achieved at 20 minutes making this a viable treatment for the community and prehospital use. A retrospective study looking at BLS crews administering prehospital intranasal naloxone over a 6-year period also showed that 95% of patients who received treatment had documented clinical benefit before arrival at the hospital. Less than 10% of patients needed additional doses in the emergency department, and 70% of patients were eventually discharged.

Children

In children less than 5 years of age or those who weigh less than 20 kg, the dose of naloxone is 0.1 mg/kg. In children who are older than 5 or weigh more than 20 kg, the dose is between 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg. Again repeat dosing may be required every 3 to 4 minutes to a maximum cumulative dose of 10mg of naloxone. Repeat dosing is often indicated when the child has ingested the longer acting opiates like methadone.

Naloxone Adverse Effects

Naloxone has been shown to have a very safe side effect profile. There have been several studies on opiate-naive patients who were given large doses of the drug without significant effects, but when given to patients who are opioid-tolerant, acute, opioid withdrawal symptoms can develop. Individuals administered naloxone in the setting of opioid overdose can experience a sudden withdrawal syndrome, which includes sudden aggression, agitation, restlessness, diaphoresis, and tachycardia. GI symptoms such as nausea and vomiting also occur in about 30% of patients. Most symptoms are not very severe or sustained, and less than 1% of patients require admission. Acute withdrawal symptoms are more likely when larger doses of naloxone are used.

Inpatient Care

The majority of patients who have overdosed on opiates and who are reversed with naloxone are admitted for observation for at least 12 to 24 hours. Naloxone has a half-life of one hour, and some long-acting opiates may continue to cause sedation and respiratory depression. The opiate overdosed patient is best admitted to a monitored floor. When it comes to a heroin overdose, the majority of patients are admitted because this illicit drug can cause acute lung injury at the same time. Most patients with acute lung injury usually present early in the course. Patients with heroin overdose who are asymptomatic may not require 24-hour monitoring, but they still need the 6 to 12-hour monitoring and discharged as long as the patient’s vital signs remain stable.

Others who do require admission are those who need multiple doses or prolonged intravenous infusions of naloxone to reverse the opiate. If there is any doubt about the patient’s clinical status, admission is prudent.

Mortality/Morbidity

Following an opiate overdose, the major cause of morbidity and mortality is due to respiratory depression. Rarely the individual may develop seizures, acute lung injury and adverse cardiac events. In individuals with prior lung pathology who overdose on opiates, the risk of respiratory distress and death is much higher than in the normal population. The other reason for the opiate toxicity may be due to coingestants, and the eventual toxicity depends on the type of co-ingestant. In one Canadian study, the risk of fatal opiate toxicity was doubled when the opiate was ingested with gabapentin; the latter is also known to depress respiration. Finally, the morbidity and mortality also depend on the reason why the opiate was ingested; some people are intent on committing suicide, and these individuals often take several other drugs at the same time, thus, greatly increasing the risk of death.

Prognosis

If the patient does arrest in the setting of a pure opiate overdose, the cause in most cases is severe hypotension, hypoxia and poor perfusion of the brain. The outcome for these patients is poor.

Complications

Opiates are also associated with a few other complications besides the usual respiratory and CNS adverse effects.

Acute Lung Injury

Acute lung injury is well known to occur after a heroin overdose. However, acute lung injury can also occur following methadone and propoxyphene overdose and is universally present in patients who expire from a high dose of opiate. As to how these opiates cause lung injury is not fully understood, but the eventual result is hypoventilation and hypoxia. Clinically, heroin-induced lung injury will present with sudden onset of dyspnea, frothy sputum, cyanosis, tachypnea, and rales- features consistent with pulmonary edema. Acute lung injury is also known to occur in children who have ingested high doses of opiates. Acute lung injury is very similar to ARDS in presentation, and most cases clear up with aggressive airway management and oxygen. The usual drugs used to manage pulmonary edema are not used, and in fact, the use of diuretics may exacerbate the hypotension.

Infection

In individuals who use intravenous opioids, complications include abscess, cellulitis, and endocarditis. The most common organisms involved are the gram-positive bacteria like Staphylococcus and Streptococci. If the bacteria enter the systemic circulation, the risk of epidural abscess and vertebral osteomyelitis are other potential complications. These patients may present with fever and continuous back pain. Some IV drug abusers are known to inject the opiates directly into the neck, and this can lead to jugular vein thrombophlebitis, Horner syndrome and even pseudoaneurysms of the carotid artery. Both peripheral and pulmonary emboli have been reported in IV drug users. Accidental injection into the nerves has also been reported to cause permanent neuropathy.

Endocarditis is a serious complication of intravenous drug abuse. Often these individuals use a mixture of illicit drugs and dirty needles. The diagnosis of infectious endocarditis is often difficult as the symptoms are vague initially. Although in most cases, the right-sided heart valves are affected, sometimes the left-sided valves may also be involved. The most common valves involved in intravenous drug users is the tricuspid valve. It often presents with fever, malaise and a new murmur. In some patients, recurrent septic pulmonary embolism may be the only presenting feature.

Other manifestations of opioid abuse may be recurrent pneumonia, and in some cases, aspiration pneumonia may also occur with the individual is unconscious. Rhabdomyolysis is not an uncommon complication of opiate overdose. It may occur even in the absence of a compartment syndrome.

Another life-threatening complication is necrotizing fasciitis that often presents with severe pain, fever, dark, dusky skin with crepitus. The individual will show signs of septic shock. Aggressive resuscitation and immediate surgical debridement can be life-saving.

Seizures: Opiates are known to increase the risk of seizures, especially drugs like propoxyphene, meperidine, pentazocine, intravenous fentanyl, and heroin. The individual may present with a prolonged seizure which may result as a result of CNS hypoperfusion and hypoxia or a result intracranial injury due to a fall.

Narcotic Bowel Syndrome

Narcotic bowel syndrome is a type of opiate bowel pathology that is characterized by frequent episodes of moderate to the severe abdominal pain that worsens with escalating or continued doses of opiates. Narcotic bowel syndrome appears to occur in people with no prior bowel pathology and is a maladaptive response. The syndrome can also be associated with intermittent vomiting, abdominal distension, and constipation. Eating always aggravates the symptoms, and the condition can last for days or weeks. Anorexia can lead to body weight loss. There is delayed gastric emptying and intestinal transit. The syndrome is often confused with bowel obstruction. The key to the diagnosis is the recognition of continued and escalating doses of opiates that worsen the abdominal pain, instead of providing relief. The treatment of narcotic bowel syndrome is some psychotherapy combined with tapering or discontinuing the opioid. The key to successful treatment is to develop a strong patient-physician relationship and trust with the patient; the narcotic should be gradually withdrawn, and other non-pharmacological treatments used to manage pain.