Endocrine System Drugs

Published (updated: ).

Antihyperglycemics – oral

Antihyperglycemic medications are used for glycemic control. Maintaining appropriate blood glucose levels in patients with hyperglycemia is important for minimizing the risk of acute symptoms, long-term complications, and mortality. There are many physiological causes of hyperglycemia, so multi-drug regimens may be required to control blood glucose levels.

Biguanides: metformin

Metformin is considered first line for treatment of type II diabetes mellitus. This oral medication is the only antihyperglycemic with evidence for decreasing premature mortality independent from glycemic control. Metformin acts as an insulin sensitizer by reducing hepatic glucose production. Metformin is contraindicated in patients with heart failure and a creatinine clearance <30 mL/min due to a risk of life-threatening lactic acidosis.

Sulfonylureas: glyburide (glibenclamide), glipizide, glimepiride

Sulfonylureas increase insulin secretion by stimulating pancreatic beta cells. Beta cells may become sensitized to these medications over time, eventually resulting in failure. Sulfonylureas may cause hypoglycemia, so dose initiation or titration should be done conservatively. Due to the risk of drug accumulation in patients with renal impairment, glyburide is not recommended, and glipizide/glimepiride should be used with caution. These drugs are associated with weight gain and an increased risk of cardiovascular death in patients with coronary artery disease.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors: empagliflozin, canagliflozin, dapagliflozin

SGLT-2 inhibitors promote glucose excretion by blocking its reabsorption in the kidney. In addition to lowering blood glucose, this class may also promote weight loss and cardiovascular benefits. The use of these medications is limited by risks, including genital infections, urinary tract infections, increased risk of bone fractures (canagliflozin), euglycemic ketoacidosis, and necrotizing fasciitis. Canagliflozin also has a black box warning for a two-fold increased risk of lower limb amputation.

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs): pioglitazone, rosiglitazone

TZDs activate nuclear transcription factor PPAR-γ, resulting in increased insulin sensitivity. Both drugs are contraindicated in patients with class III-IV heart failure due to black box warnings for increased risk of heart failure. Rosiglitazone has a second black box warning for increased risk of myocardial events. Other adverse effects that may limit utility in practice include weight gain, edema, and increased risk of fractures.

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) Inhibitors: sitagliptin, saxagliptin, alogliptin, linagliptin

Gliptins stimulate insulin release and decrease hepatic glucose production. Mild adverse effects include headache and upper respiratory infections. Serious adverse effects include acute pancreatitis, urinary tract infections, extremity/back pain or osteoarthritis (with sitagliptin only). Gliptins do not have cardiovascular benefits and may increase risk of hospitalization for heart failure.

Meglitinides: repaglinide, nateglinide

Meglitinides, similar to sulfonylureas, stimulate insulin secretion by pancreatic beta cells. This means patients may develop tolerance to these medications over time, as seen with sulfonylureas. Meglitinides, unlike sulfonylureas, have a short duration of action and primarily affect postprandial glucose level. This means patients should be instructed to take meglitinides before meals, up to three times per day. Repaglinide has similar glycated hemoglobin A1C lowering abilities and hypoglycemia risk to sulfonylureas while nateglinide is not as good at lowering A1C but provides a lower risk of hypoglycemia.

Alpha-glucosidase Inhibitors: acarbose, miglitol

These drugs inhibit intestinal alpha glucosidase, preventing the breakdown of carbohydrates into simple sugars and ultimately resulting in lower postprandial blood glucose. Acarbose is generic and commonly used, however it is contraindicated in patients with the following: cirrhosis, colonic ulcers, intestinal disease or obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease, or diabetic ketoacidosis. The increased presence of carbohydrates within the intestines results in many of the GI side effects seen with this medication class.

Antihyperglycemics – injectable

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs): liraglutide, exenatide

These medications mimic endogenous glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) resulting in a variety of effects: stimulation of insulin secretion, enhancement of insulin sensitivity (secondary to weight loss), slowing of gastric emptying, and endogenous glucose production. Liraglutide also reduces cardiovascular events and mortality for high-risk patients within 3-5 years. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and hypersensitivity reactions are the most common adverse effects.

Amylin mimetics: pramlintide

Pramlintide is a synthetic analog of human amylin, inhibiting high glucagon secretion and reducing the rate of glucose absorption by slowing gastric emptying. This medication should only be considered for patients already receiving insulin for type I or II diabetes. There is a black box warning for severe hypoglycemia, so proper insulin adjustments should be made if initiating concomitant pramlintide. Contraindications for pramlintide include gastroparesis, drugs that stimulate gastrointestinal motility, poor compliance to insulin therapy or blood-glucose monitoring, or glycated hemoglobin (A1C) > 9%.

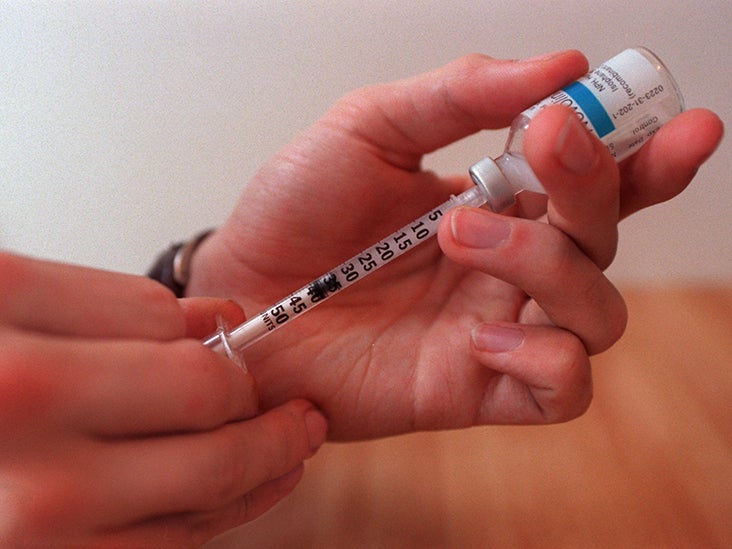

Insulin

Endogenous insulin acts to move glucose out of the blood into the cells, resulting in decreased serum glucose levels. There are two groups of exogenous insulin used for hyperglycemia: human insulin and insulin analogues. Human insulins include isophane (NPH) insulin and regular insulin and analogues include insulin aspart, lispro, glulisine, detemir, and glargine. While human insulin is more affordable, insulin analogues act more similarly to endogenous insulin produced by the pancreas. The different types of insulin vary in their onset of action, the time to their peak effects, and the duration of action.

Drugs for hyperthyroidism

Thioamides, such as carbimazole and propylthiouracil, inhibit thyroid peroxidase and interfere with the formation of thyroid hormones. Carbimazole is a prodrug metabolised to the active metabolite thiamazole (also known as methimazole). As there are thyroid hormones stored in the thyroid gland, the onset of clinical action can vary from 3 to 12 weeks. Generally, carbimazole or thiamazole is preferred to propylthiouracil as it has a longer half-life and lower risk of hepatotoxicity.

Iodides at high concentrations activate the Wolff-Chaikoff effect, an autoregulatory phenomenon suppressing thyroid hormone synthesis and the release of thyroid hormones

Drugs for hypothyroidism

Levothyroxine is a synthetic form of the thyroid hormone thyroxine (T4). Levothyroxine is commonly used for oral replacement therapy in the treatment of hypothyroidism. It has poor and variable oral bioavailability (40% to 80%) that can be decreased by age, foods, and certain drugs. Typically it should be taken with water only on an empty stomach 30 minutes to one hour before food, one hour before taking food, soya milk, coffee or bulk-forming laxatives (dietary fibre), and four hours before iron or calcium supplements or antacids. The major adverse effects are due to the risk of hyperthyroidism on overdose. Risks include cardiac arrest, hypertension, palpitations, tachycardia, anxiety, heat intolerance, hyperactivity, insomnia, irritability, and weight loss. Long-term use of high doses has been associated with increased bone resorption and reduced bone mineral density, especially in post-menopausal women.

Liothyronine is a synthetic form of the thyroid hormone triiodothyronine (T3). Liothyronine is administered intravenously and orally for the treatment of myxoedema. Oral liothyronine is also sometimes used in combination with levothyroxine for chronic replacement therapy in patients with persistent complaints impacting their quality of life after levothyroxine alone. However, the benefits and long-term safety of combination replacement therapy remain inconclusive.