SCUBA Diving Emergencies

Published (updated: ).

Introduction

According to the Sports and Fitness Industry Association 2015 report, there are approximately three million people who engage in scuba diving-related activities in the United States every year, and more than nine million people identify themselves as recreational divers. The incidence of diving-related accidents has increased steadily with the increase in divers. Despite the many improvements in technology and safe-diving techniques, the rate of recreational scuba diving fatalities remains steady at about two fatalities per 100,000 dives. The Divers Alert Network (DAN) identifies more than 1000 diving-related injuries annually, with over 10% of those being fatal. DAN groups these incidents into four major categories under which most diving-related casualties can be grouped. These include preexisting medical conditions of divers, procedural errors, changes in an environment, and problems with equipment. The incidence and

Issues of Concern

According to the most recent report issued by the Divers Alert Network (DAN), there were approximately 146 identified recreational scuba-related fatalities worldwide in 2014. Of these 146 deaths, 68 cases occurred in the United States and Canada. It is essential to understand different types of dives, the risks associated with each, the most cited problems leading to fatalities during diving, and safety techniques that can substantially decrease the risk of accidents while diving.

Examples of medical conditions leading to decreased diver safety include obesity, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, pulmonary disease, and lack of physical fitness. Medical information available on the deceased revealed that 51% were obese (BMI greater than 30) and a further 29% were overweight (BMI 25 to 29). Age is strongly correlated with the risk of fatality, with over half of cases identified involving divers over the age of 50. Over 15% of cases were known to involve individuals with cardiovascular disease or hypertension. Even seemingly minor medical conditions such as allergies can lead to significant problems such as middle ear and sinus barotrauma. Furthermore, diving soon after a respiratory illness can lead to inadequate ventilation and cause panic, leading to depletion of the diver’s oxygen at a more rapid rate.

Procedural errors listed in the DAN report include problems with air supply management, rapid ascents with missed decompression stops, improper breathing techniques, and problems with buoyancy. Running out of gas was listed as the precipitating factor leading to death in over 10% of cases, and many other cases describe risks taken to maximize gas and dive time such as inexperienced divers using rebreathers and other complicated diving equipment. The leading modifiable causes of death identified were cardiovascular events, insufficient gas in rebreather chambers, and arterial gas embolism. Many cases describe situations in which divers engage in dives above their skill level or with the equipment with which they are not familiar, leading to panic and decision making that would not typically be expected.

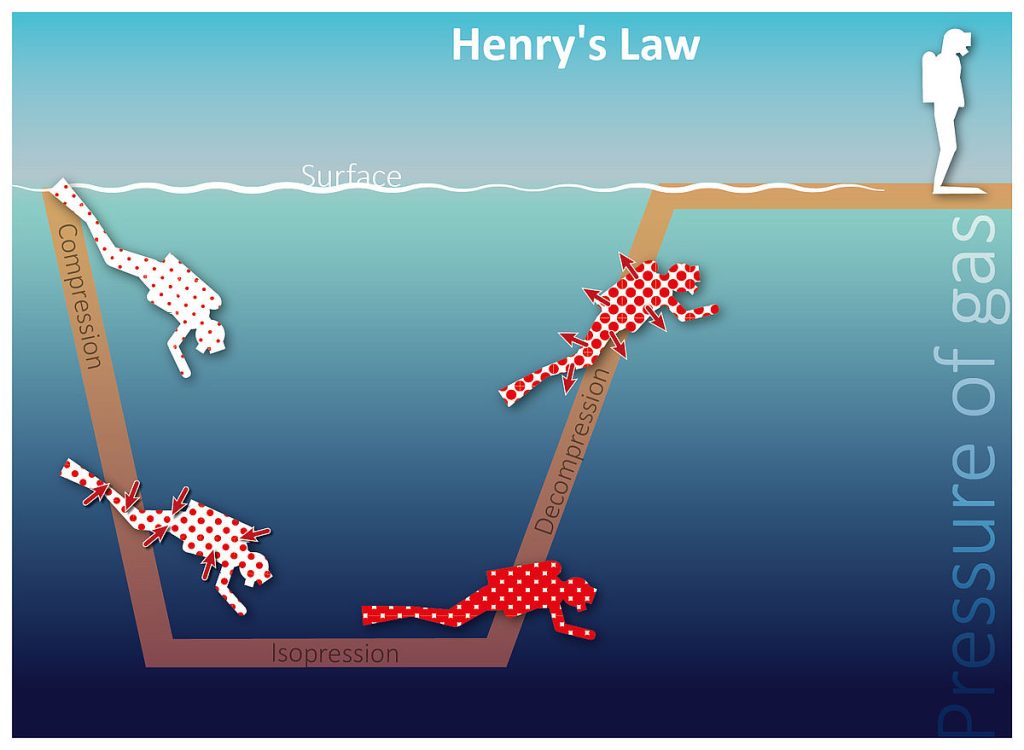

Decompression illness is often the result of procedural errors leading to rapid ascents, breathing errors, or problems in time spent at certain depths. Decompression illness is usually divided into arterial gas embolism and decompression sickness. Arterial gas embolism (AGE) develops when divers hold their breath during ascent, leading to expansion and rupture of the alveoli. This leads to bubbles being introduced to the left side circulation and traveling to the brain and the heart. AGE can occur in as little as six feet of water and does not depend on the nitrogen load of the diver. Physiologically, these bubbles can denature proteins and stimulate leukocytes to activate and damage the endothelium, leading to edema, hemorrhage, infarcts, and eventually cell death. Decompression sickness is caused by dissolved inert gas coming out of solution and leading to the formation of bubbles. The amount of dissolved gas depends upon the depth and time of the dive and can be determined using dive charts or dive computers. When these limits are exceeded, bubbles begin to form most commonly in the blood and tissues of the spine, nerves, joints, and skin.

Environmental issues identified by DAN involve problems such as changes in weather, currents, tide, water temperatures, and visibility. Some cases involve rapid changes in visibility while divers were exploring caves or shipwrecks which led to the divers to become trapped and run out of gas. There were also cases that described increasing currents and waves making it impossible for divers who were not physically fit to handle the changing conditions. The DAN report cited visibility in 31% of cases, changing sea conditions in 37% of cases, and changing currents in 34% of cases as a factor in diver fatality.

Problems with equipment also play a role in diver fatality, with the most common issues related to improper use or malfunction of buoyancy control, regulator issues, problems with rebreather devices, and failure of dive computers. Multiple cases describe divers using new buoyancy control devices that they are unfamiliar with and failing to establish neutral buoyancy. These involve both uncontrolled ascents and descents leading to drowning and death. Malfunctions with dive computers have also led to divers spending too much time at certain depths or ascending too quickly resulting in decompression sickness. Although the equipment has played a role in a number of diving-related accidents, the prevalence is much less than the other common factors cited in diver fatalities.

It is also important to consider the type of dive in relation to the potential for fatality. Of the cases described in the DAN report, 66% involved recreational dives, 21% involved commercial diving activities, and 12% were involved in training exercises. Included in the recreational category are fatalities related to lobster hunting, which account for 15% of overall fatalities. Lobster diving fatalities are very dangerous due to the increased equipment requirements, focus on the hunt as opposed to gas levels, and the frequency with which lobster divers are active. As lobster divers only dive seasonally and they are often out of practice when the lobster diving season begins. Tens of thousands of Americans participate in lobster hunting every year, and improvements in safe practices related to this sport can result in a large decrease in yearly diving-related casualties.

Diving accidents are a common occurrence and account for more than 1000 emergency department visits per year in the United States. While this rate has remained steady for many years, the hope that increasing awareness, as well as technological improvements, will lead to a decrease in future casualties. All divers should be aware of the annual Divers Alert Network report that provides case studies of recent accidents and the steps that could have been taken to prevent them.

Treatment

The treatment for decompression illness is recompression. Early management of arterial gas embolism and decompression sickness is the same. It is essential that a diver with arterial gas embolism or severe decompression sickness to be stabilized at the nearest medical facility before being transported to a hyperbaric chamber.

Early oxygen first aid is essential and may reduce symptoms, but this should not change the treatment plan. Symptoms of arterial gas embolism and severe decompression sickness often resolve after breathing oxygen from a cylinder, but they may reappear later.

Delays in seeking treatment elevate the risk of residual symptoms. Over time the initially reversible damage may become permanent. After a delay of 24 hours or more, treatment may be less effective, and symptoms may not respond. Even if there has been a delay, consult a diving medical specialist before making any conclusions about possible treatment effectiveness.