The Skull

Published .

Introduction

The cranium (Latin term for skull) is the most cephalad aspect of the axial skeleton. It is composed of 22 bones and divided into two regions: the neurocranium (which protects the brain) and the viscerocranium (which forms the face). The skull also supports tendinous muscle attachments and allows neurovascular passage between intracranial and extracranial anatomy. The skull is embryologically derived from mesoderm and neural crest and will fuse, harden, and mold from gestation through adulthood. It gives the human face its form, and even minor variations in anatomy among individuals can lead to wide differences in appearance. Various foramina, condyles, and other bony landmarks provide passageways and attachments for the important structures associated with the skull.

Structure and Function

The skull consists of 22 bones in most adult specimens, and these bones come together via cranial sutures. The function of the skull is both structurally supportive and protective. The skull will harden and fuse through development to protect its inner contents: the cerebrum, cerebellum, brainstem, and orbits. It supports the muscles of the face and scalp by providing muscular and tendinous attachments, protects neurovascular structures, and houses various sinuses to accommodate increases in pressure.

Calvaria and Skull Base

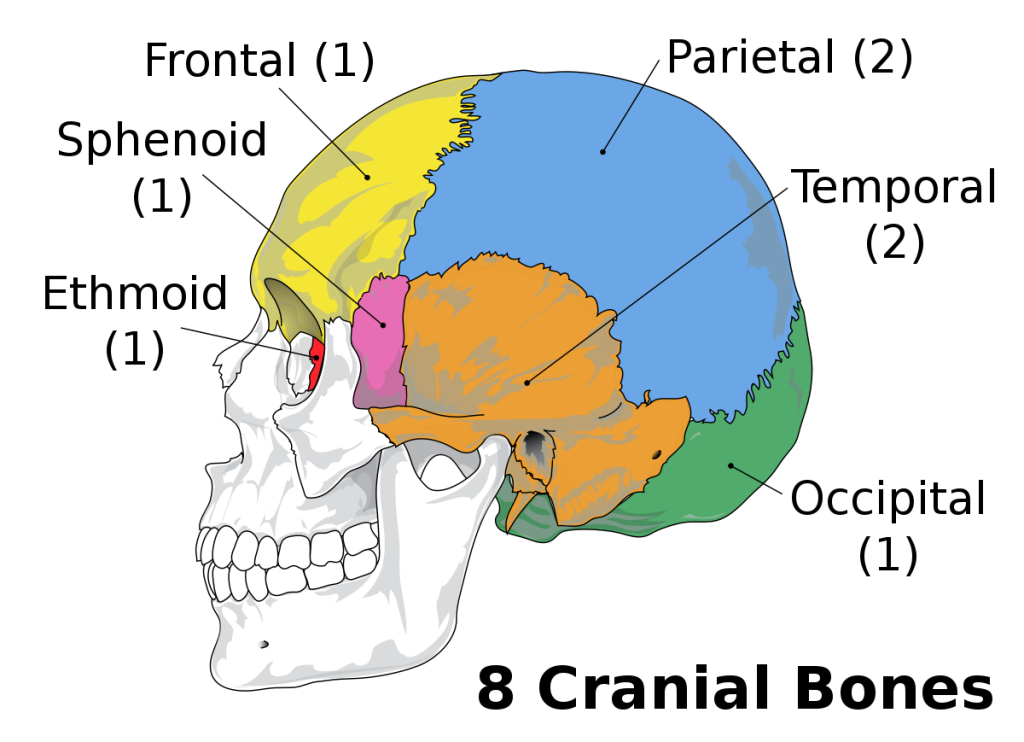

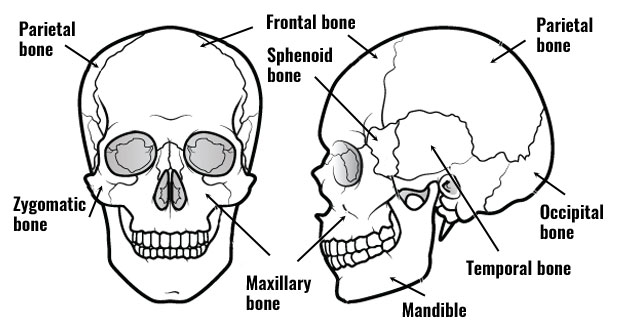

The calvaria, the uppermost part of the skull, protects the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and orbital contents. It is composed of the frontal bone, parietal bones, temporal bones, and occipital bone. The coronal suture is the transverse mid-anterior junction of the frontal bone and the two parietal bones. The parietal bones articulate with the temporal bones inferiorly via the squamosal sutures and the occipital bone posteriorly via the lambdoid suture. The sagittal suture lies along an anterior-posterior axis and is the articulation of the two parietal bones. The pterion is the articulation of the frontal, parietal, temporal, and sphenoid bones just superior to the pinna. The asterion is the articulation of the parietal, temporal, and occipital bones. Finally, the skull base allows the passage of various neurovascular structures and is composed of the sphenoid bone and ethmoid bone (which have their own associated air sinuses), as well as parts of the frontal, temporal, and occipital bones.

Anteriorly, the frontal bone forms the superior aspect of the orbits. The glabella is a key midline landmark of the frontal bone. It lies superior to the nasion and between the superciliary ridges. The frontal sinuses lie deep to the brow ridges. The bregma is the junction of the coronal and sagittal sutures, and lambda is the junction of the lambdoid and sagittal sutures. The temporal bones subdivide into petrous, squamous, zygomatic, and mastoid parts. The petrous portion houses the inner ear. The mastoid is a bony prominence that lies posterior to the auricle and also has an associated sinus. The occipital bone is the most posterior aspect of the skull.

Intracranial Fossae

There are three cranial fossae with various structural landmarks. The anterior cranial fossa forms from the frontal bone, the sphenoid bone, and the ethmoid bone. The middle cranial fossa forms from the sphenoid bone and two temporal bones. Finally, the posterior cranial fossa forms from the occipital bone and two temporal bones. The critical anatomic landmarks of each fossa are listed below.

- Anterior Cranial Fossa

- Cribriform plate

- Middle Cranial Fossa

- Optic canal

- Superior orbital fissure

- Foramen spinosum

- Foramen rotundum

- Foramen ovale

- Posterior Cranial Fossa

- Internal auditory meatus

- Jugular foramen

- Foramen magnum

- Hypoglossal canal

Facial Bones

There are 14 facial bones with very specific anatomical landmarks and embryologic development mechanisms. These include the two nasal conchae, two nasal bones, two maxilla bones, two palatine bones, two lacrimal bones, two zygomatic bones, the mandible, and the vomer. The maxillae have associated air sinuses. The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is an especially important landmark for effective mastication, and its dysfunction is common in the adult population

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Most of the blood supply to the skull and its associated structures comes from the common carotid arteries (anterior circulation) and vertebral arteries (posterior circulation). The common carotid artery splits into the internal and external carotid arteries. The external carotid is the main blood supply to the skull bones and meninges. It travels up the side of the neck with eight main branches feeding the superficial structures of the skull and face. Of these branches, the maxillary artery is the most prominent and clinically relevant. The middle meningeal artery is a branch of the maxillary artery, and injury secondary to blunt force trauma to the lateral skull at the pterion can lead to epidural hematoma. The internal carotid has no branches in the neck and enters the base of the skull, supplying intracranial structures. The internal carotid and vertebral arteries combine to form a large anastomosis called the circle of Willis. The anterior communicating artery, two anterior cerebral arteries, two middle cerebral arteries, two posterior communicating arteries, two posterior cerebral arteries, and basilar artery (superior continuation of the vertebral arteries) all contribute to this anastomosis. The dural venous sinuses (i.e., superior sagittal, straight, and transverse sinuses) and superficial and deep veins of the head (i.e., cerebral veins, great vein of Galen, cerebellar, and facial veins) drain into the internal and external jugular veins bilaterally and ultimately to the superior vena cava and right atrium of the heart.

The brain and central nervous system have been traditionally thought not to contain lymphatic vessels. However, some believe that the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) does have some connection with the lymphatic system and drains through the cervical lymph nodes. The recent discovery of a “glymphatic system,” composed of a network of CSF, interstitial cerebral fluid, and meningeal vasculature, has shed more light on this debate and is an area of ongoing research.

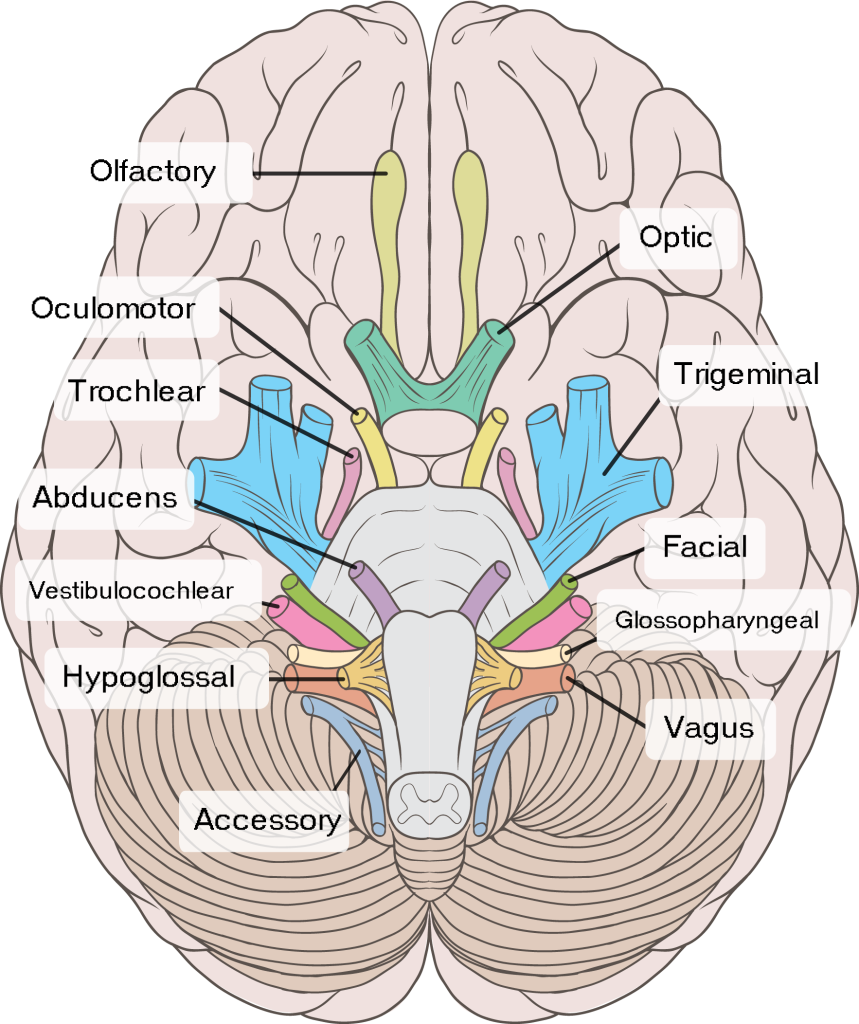

Nerves

The skull has multiple foramina that allow passage into and out of the skull for blood vessels and nerves. The cranial nerves mostly exit via foramina in the cranial base. A brief list of the most important foramina and their associated cranial nerves appear below.

- Cribriform Plate → olfactory nerve (CN I)

- Optic Canal → optic nerve (CN II)

- Also: ophthalmic artery

- Superior Orbital Fissure → oculomotor nerve (CN III), trochlear nerve (CN IV), abducens nerve (CN VI), ophthalmic division of trigeminal nerve (CN V1)

- Foramen rotundum → maxillary division of trigeminal nerve (CN V2)

- Foramen Ovale → mandibular division of trigeminal nerve (CN V3)

- Stylomastoid Foramen → facial nerve (CN VII)

- Internal Auditory Meatus → facial nerve (CN VII) and vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII)

- Jugular Foramen → glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX), vagus nerve (CN X), and spinal accessory nerve (CN XI)

- Also: jugular vein

- Hypoglossal Canal → hypoglossal nerve (CN XII)

- Foramen Magnum → brainstem and spinal root of accessory nerve (CN XI)

- Also: vertebral arteries

Other key foramina that may or may not be associated with nerves include the foramen spinosum (middle meningeal artery), carotid canal (internal carotid artery and sympathetic plexus), and supraorbital and infraorbital foramina (supraorbital and infraorbital nerves). The superficial sensory nerves of the skull, scalp, and face receive input from branches of the trigeminal nerve anteriorly and the greater and lesser occipital nerves posteriorly.

Fontanelles and Cranial Sutures

Fontanelles are soft areas where the skull has not ossified to allow for brain growth and development. There are six fontanelles, with the anterior and posterior being the most prominent and clinically significant. The anterior fontanelle closes around age 1-2 and hardens to become the bregma and adjacent coronal suture. The posterior fontanelle closes around 6-8 weeks of age and becomes the lambda and adjacent lambdoid suture.

The sutures of the skull allow for movement of the cranial bones during infancy, and this persists into adulthood. Eventually, these sutures fuse and are no longer moveable. There is a great deal of variation in the timing of the closure of individual sutures. The sagittal suture closes first around age 22, then the coronal suture, followed by the lambdoid around age 26, and the squamous sutures around age 60. The metopic suture splits the frontal bones and typically closes at three months of age but can take up to 9 months.