PASG or MAST

Published (updated: ).

A g-suit, or anti-g suit, is a flight suit worn by aviators and astronauts who are subject to high levels of acceleration force (g). It is designed to prevent a black-out and g-LOC (g-induced loss of consciousness) caused by the blood pooling in the lower part of the body when under acceleration, thus depriving the brain of blood. Black-out and g-LOC have caused a number of fatal aircraft accidents.

If blood is allowed to pool in the lower areas of the body, the brain will be deprived of blood. This lack of blood flow to the brain first causes a greyout (a dimming of the vision also called brownout), followed by tunnel vision and ultimately complete loss of vision ‘blackout’ followed by g-induced Loss Of Consciousness or ‘g-LOC’. The danger of g-LOC to aircraft pilots is magnified because on relaxation of g-force there is a period of disorientation before full sensation is re-gained. A g-suit does not so much increase the g-threshold, but makes it possible to sustain high g longer without excessive physical fatigue. The resting g-tolerance of a typical person is anywhere from 3–5 g depending on the person. A g-suit will typically add 1 g of tolerance to that limit. Pilots still need to practice the ‘g-straining maneuver’ that consists of tensing the abdominal muscles in order to tighten blood vessels so as to reduce blood pooling in the lower body. High g is not comfortable, even with a g-suit. In older fighter aircraft, 6 g was considered a high level, but with modern fighters 9 g or more can be sustained structurally making the pilot the critical factor in maintaining high maneuverability in close aerial combat.

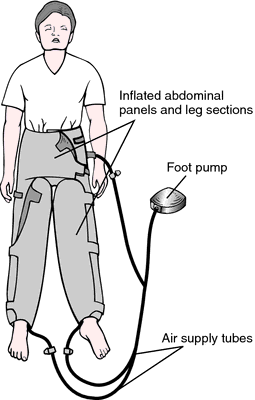

Medical anti-shock trousers (MAST), also known as military anti-shock trousers or pneumatic anti-shock garments (PASG), are medical devices made of synthetic inflatable air bladders which are applied to a patient’s abdomen, pelvis, and lower extremities. These devices include one abdominal compartment and 2 leg compartments which attach to a pump or inflation unit with valves to control the pressure within each air bladder. The underlying physiologic concept of these devices is simple; apply pressure to the lower extremities to auto-transfuse or shift the patient’s blood volume from the abdomen, pelvis, and lower extremities to the upper body and central circulation. At one time it was also thought these devices increased overall peripheral vascular resistance, halted intraabdominal and lower extremity bleeding, and splinted lower extremity fractures.

Medical anti-shock trousers were first described in 1903 by surgeon G.W. Crile as he tried to augment blood pressure with a “pneumatic rubber suit” during neurosurgical procedures. Decades later the term military anti-shock trouser was coined during the Vietnam War where medics applied the device in the field before airlifting soldiers out of a combat zone to a hospital for definitive care. Upon conclusion of the Vietnam War in 1975 military surgeons and combat medics returned to the United States and advocated for the use of these devices in pre-hospital and critical care settings. In 1977 the Committee on Trauma for the American College of Surgeons listed MAST as essential devices on all ambulances. Throughout the United States in the late 1970s and 1980s MAST devices were the standard of care for hypotensive trauma patients as evidenced by the American College of Surgeons’ Advanced Trauma Life Support guidelines. These devices were utilized heavily through the 1980s and as late as 1996 there were 30 states which required MAST devices on all ambulances. These devices were applied in various settings including aviation, combat, pre-hospital and critical care settings.

Despite a period of widespread use, MAST devices have been the subject of much debate and research and are currently rarely used. Initial studies in the 1970s suggested that as much as 20% of a patient’s total blood volume was auto-transfused to the upper body by application of the MAST device. Further studies performed in the 1980s, however, refuted these early findings, suggesting that only 5% or less of a patient’s overall blood volume was auto-transfused by these devices in both human and dog models. During this period there were also studies that showed harmful complications of device use which included compartment syndrome and lower extremity ischemia, amongst others. In 1989, the Houston Fire Department partnered with Ben Taub Hospital to investigate the use of MAST devices in the prehospital environment. This study, which enrolled 201 patients randomized either to MAST application or standard care, did not demonstrate an improvement in mortality rates in penetrating abdominal trauma. Further studies corroborated these findings and could not show a significant difference in the length of hospitalization or intensive care unit stay. Amidst this controversy, the National Association of Emergency Medical Services Physicians published a 1997 position paper citing support for MAST in certain cases including ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, pelvic fracture with subsequent hypotension, and severe traumatic hypotension.

The MAST device is applied approximately 1-inch inferior to the costal margin and covers the abdomen, pelvis, and lower extremities.

Currently, there are no widely accepted indications for the use of these devices. Specifically, the American College of Surgeons’ Advanced Trauma Life Support and American College of Emergency Physicians’ guidelines do not specifically recommend the use of these devices. Indications include:

- Hypotension associated with a suspected pelvic and/or femur fractures

- Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Stabilization of pelvic and femur fractures

Contraindications include:

- Congestive heart failure (CHF)

- Myocardial infarction

- Stroke

- Pregnancy

- Thoracic hemorrhage

- Diaphragmatic injury

- Head injuries

- Abdominal injury with evisceration

- Uncontrolled bleeding above the level of the garment

- Impaled object to the abdomen or lower extremity

Only medical professionals who have received appropriate training should deploy the MAST device. These persons include but are not limited to physicians, nurses, and emergency medical personnel. It requires only 1 trained person to apply the MAST device.

Preparation

Place the MAST device on a stretcher or long backboard before transferring the patient. Transfer the patient over to the stretcher or backboard and perform a physical examination to identify contraindications for MAST application or injuries which the device will cover once inflated. Apply and inflate the MAST device if no contraindications exist.

Technique

- Evaluate the need for MAST by assessing injuries and obtaining vital signs.

- Unfold MAST and lay it flat on a backboard or stretcher before moving the patient.

- Perform a secondary survey to identify injuries that the device will be covering, dressing wounds as necessary. Remove all clothing and foreign objects as these will be pressed into the patient’s skin by the device.

- While maintaining immobility of the spine, place the patient on the MAST device so that the top of the garment is approximately 1 inch inferior to the costal margin.

- Secure and fasten the leg sections. Ensure all creases are removed.

- Secure and fasten the abdominal section (unless contraindicated). Ensure all creases are removed and that the garment has not changed position relative to the patient’s chest wall.

- Attach the pump and check all valves for closure.

- Inflate leg compartments.

- Re-assess the patient and obtain repeat vital signs.

- If the patient’s systolic blood pressure is between 100 to 110 mm Hg, ensure valves are closed and continue to monitor the patient’s blood pressure. Do not attempt to increase the systolic blood pressure beyond 110 mm Hg.

- If the patient’s systolic blood pressure is not between 100 to 110 mm Hg, inflate the abdominal compartment (unless contraindicated).

- Continue monitoring the patient’s systolic blood pressure, adding air to the device as needed to maintain a systolic blood pressure between 100 to 110 mm Hg.

- Remove MAST only when the patient has been adequately resuscitated and under the direction of a physician in a controlled setting.

Complications

- Lower extremity ischemia

- Compartment syndrome

- Respiratory failure

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Acute kidney injury

- Metabolic acidosis

Clinical Significance

MAST devices are still discussed in protocols and textbooks for several EMS agencies in the United States. Most hospital systems and EMS agencies, however, have abandoned the use of these devices due to the paucity of supporting evidence and the relatively high cost compared to other treatment modalities. There are no widely accepted indications for MAST use and doing so falls outside the standard of medical care in most developed nations.