Peritoneal & Retroperitoneal Structures

Published .

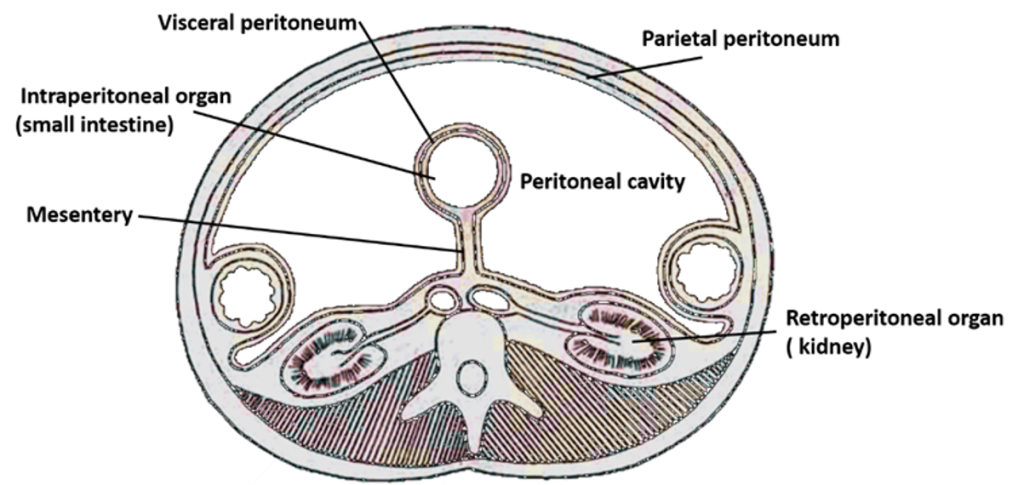

The peritoneum is the serous membrane that lines the abdominal cavity. It is composed of mesothelial cells that are supported by a thin layer of fibrous tissue and is embryologically derived from the mesoderm. The peritoneum serves to support the organs of the abdomen and acts as a conduit for the passage of nerves, blood vessels, and lymphatics. Although the peritoneum is thin, it is made of 2 layers with a potential space between them. The potential space between the 2 layers contains about 50 to 100 ml of serous fluid that prevents friction and allows the layers and organs to glide freely. The outer layer is the parietal peritoneum, which attaches to the abdominal and pelvic walls. The inner visceral layer wraps around the internal organs located inside the intraperitoneal space. The structures bound by the peritoneal cavity may be intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal.

Structure and Function

The boundaries of the peritoneal cavity include:

- Anterior abdominal muscles

- Vertebrae

- Pelvic floor

- Diaphragm

The peritoneum is comprised of 2 layers: the superficial parietal layer and the deep visceral layer. The peritoneal cavity contains the omentum, ligaments, and mesentery. Intraperitoneal organs include the stomach, spleen, liver, first and fourth parts of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, transverse, and sigmoid colon. Retroperitoneal organs lie behind the posterior sheath of the peritoneum and include the aorta, esophagus, second and third parts of the duodenum, ascending and descending colon, pancreas, kidneys, ureters, and adrenal glands.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The parietal peritoneum receives blood from the abdominal wall vasculature, including the iliac, lumbar, epigastric, and intercostal arteries. The visceral peritoneum receives supply from the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. The two portions of the peritoneum also differ in their venous drainage: the parietal peritoneum drains into the inferior vena cava while the visceral peritoneum drains into the portal vein

Nerves

A thorough understanding of the innervation of the peritoneum is important as it has clinical implications. The peritoneum has both somatic and autonomic innervations that help explain why various abdominal pathologies, such as peritonitis or appendicitis present the way they do. The parietal peritoneum receives its innervation from spinal nerves T10 through L1. This innervation is somatic and allows for the sensation of pain and temperature that can be localized. The visceral peritoneum receives autonomic innervation from the Vagus nerve and sympathetic innervation that result in the difficult to localize abdominal sensations triggered by organ distension.