Spontaneous Pneumothorax

Published (updated: ).

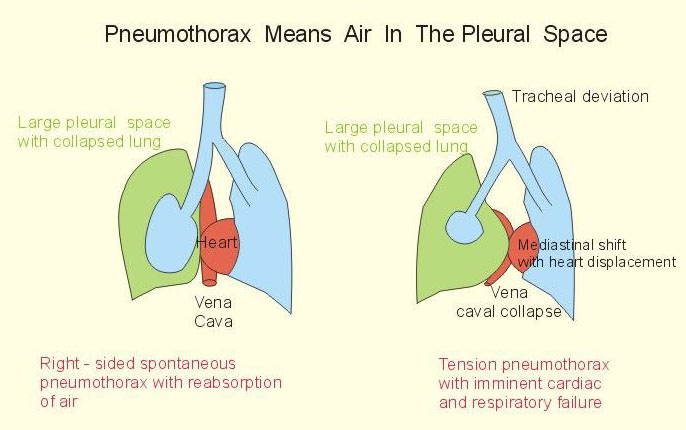

Spontaneous pneumothorax refers to the abnormal collection of gas in the pleural space between the lungs and the chest wall. Spontaneous pneumothorax occurs without an obvious etiology such as trauma. Spontaneous pneumothorax can be classified as either primary or secondary. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) occurs when the patient does not have a history of the underlying pulmonary disease, whereas secondary spontaneous pneumothorax (SSP) is associated with a history of an underlying pulmonary disease. Patients may present with a variety of symptoms including tachycardia and dyspnea. A feared complication is tension pneumothorax. The diagnosis of spontaneous pneumothorax is based on clinical suspicion and can be confirmed with imaging. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax depends on multiple factors including the patient’s stability, the size of the pneumothorax, occurrence (i.e., first episode or recurrent), and the type of spontaneous pneumothorax (i.e., primary spontaneous pneumothorax or secondary spontaneous pneumothorax).

Etiology

While primary spontaneous pneumothorax is not associated with underlying pulmonary disease, secondary spontaneous pneumothorax is associated with, but not limited to, the following:

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Asthma

- Cystic fibrosis

- Pneumonia (e.g., necrotizing, Pneumocystis jirovecii)

- Pulmonary abscess

- Tuberculosis

- Malignancy

- Interstitial lung disease (e.g., idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, sarcoidosis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis)

- Connective tissue disease (e.g., Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis)

- Pulmonary infarct

- Foreign body aspiration

- Catamenial (i.e., associated with menses secondary to thoracic endometriosis)

- Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome

Epidemiology

Spontaneous pneumothorax occurs more frequently in adults than children and more frequently in males than females. In the United States, the adult incidence of primary spontaneous pneumothorax is estimated to be 7.4-18/100,000 population per year in males and 1.2-6.0/100,000 population per year in females, with similar rates of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax in males and females, 6.3 and 2.0, respectively, per 100,000 population per year. In children, the combined incidence of spontaneous pneumothorax is estimated to be 4.0/100,000 population per year in males and 1.1/100,000 population per year in females. Other risk factors include a history of smoking, and a tall, thin body habitus.

History and Physical

Spontaneous pneumothorax most commonly occurs at rest without a history of an exertional component. Patients are often complaining of sharp, pleuritic chest pain or acute dyspnea and increased work of breathing, especially patients with secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. Tachycardia is one of the most common physical exam findings; however, in patients with smaller spontaneous pneumothorax (less than 15% of the hemithorax), the exam may be unremarkable. For patients with larger spontaneous pneumothorax (more than 15%), there may be reduced movement of the chest wall, ipsilateral decreased or absent breath sounds, jugular venous distension, hyperresonance on percussion, and decreased tactile fremitus. Development of a tension pneumothorax is a rare potential complication of spontaneous pneumothorax with the late, ominous findings of hypoxemia, hypotension, and tracheal deviation.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of spontaneous pneumothorax is often suggested by the patient’s history and physical exam findings, which can be confirmed by imaging. Chest radiography characteristically shows the displacement of the visceral pleural line with a space devoid of lung markings in between. While upright films are preferred, there is evidence that expiration does not necessarily increase the diagnostic yield.