The Immune System

Published .

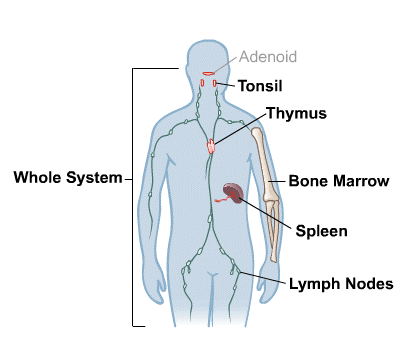

The immune system has a vital role: It protects your body from harmful substances, germs and cell changes that could make you ill. It is made up of various organs, cells and proteins.

As long as your immune system is running smoothly, you don’t notice that it’s there. But if it stops working properly – because it’s weak or can’t fight particularly aggressive germs – you get ill. Germs that your body has never encountered before are also likely to make you ill. Some germs will only make you ill the first time you come into contact with them. These include childhood diseases like chickenpox.

The tasks of the immune system

Without an immune system, we would have no way to fight harmful things that enter our body from the outside or harmful changes that occur inside our body. The main tasks of the body’s immune system are

- to fight disease-causing germs (pathogens) like bacteria, viruses, parasites or fungi, and to remove them from the body,

- to recognize and neutralize harmful substances from the environment, and

- to fight disease-causing changes in the body, such as cancer cells.

How is the immune system activated?

The immune system can be activated by a lot of different things that the body doesn’t recognize as its own. These are called antigens. Examples of antigens include the proteins on the surfaces of bacteria, fungi and viruses. When these antigens attach to special receptors on the immune cells (immune system cells), a whole series of processes are triggered in the body. Once the body has come into contact with a disease-causing germ for the first time, it usually stores information about the germ and how to fight it. Then, if it comes into contact with the germ again, it recognizes the germ straight away and can start fighting it faster.

The body’s own cells have proteins on their surface, too. But those proteins don’t usually trigger the immune system to fight the cells. Sometimes the immune system mistakenly thinks that the body’s own cells are foreign cells. It then attacks healthy, harmless cells in the body. This is known as an autoimmune response.

Innate and adaptive immune system

There are two subsystems within the immune system, known as the innate (non-specific) immune system and the adaptive (specific) immune system. Both of these subsystems are closely linked and work together whenever a germ or harmful substance triggers an immune response.

The innate immune system provides a general defense against harmful germs and substances, so it’s also called the non-specific immune system. It mostly fights using immune cells such as natural killer cells and phagocytes (“eating cells”). The main job of the innate immune system is to fight harmful substances and germs that enter the body, for instance through the skin or digestive system.

The adaptive (specific) immune system makes antibodies and uses them to specifically fight certain germs that the body has previously come into contact with. This is also known as an “acquired” (learned) or specific immune response.

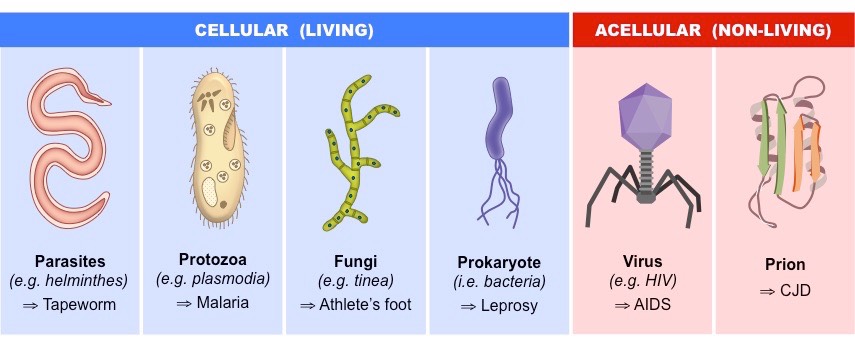

Infectious Agents

Infectious diseases can be caused by several different classes of pathogenic organisms (commonly called germs). These are viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and fungi. Almost all of these organisms are microscopic in size and are often referred to as microbes or microorganisms.

Although microbes can be agents of infection, most microbes do not cause disease in humans. In fact, humans are inhabited by a collection of microbes, known as the microbiome, that plays important and beneficial roles in our bodies.

The majority of agents that cause disease in humans are viruses or bacteria, although the parasite that causes malaria is a notable example of a protozoan.

Examples of diseases caused by viruses are COVID-19, influenza, HIV/AIDS, Ebola, diarrheal diseases, hepatitis, and West Nile. Diseases caused by bacteria include anthrax, tuberculosis, salmonella, and respiratory and diarrheal diseases.

Transmission of Infectious Diseases

There are a number of different routes by which a person can become infected with an infectious agent. For some agents, humans must come in direct contact with a source of infection, such as contaminated food, water, fecal material, body fluids or animal products. With other agents, infection can be transmitted through the air.

The route of transmission of infectious agents is clearly an important factor in how quickly an infectious agent can spread through a population. An agent that can spread through the air has greater potential for infecting a larger number of individuals than an agent that is spread through direct contact.

Another important factor in transmission is the survival time of the infectious agent in the environment. An agent that survives only a few seconds between hosts will not be able to infect as many people as an agent that can survive in the environment for hours, days, or even longer. These factors are important considerations when evaluating the risks of potential bioterrorism agents.