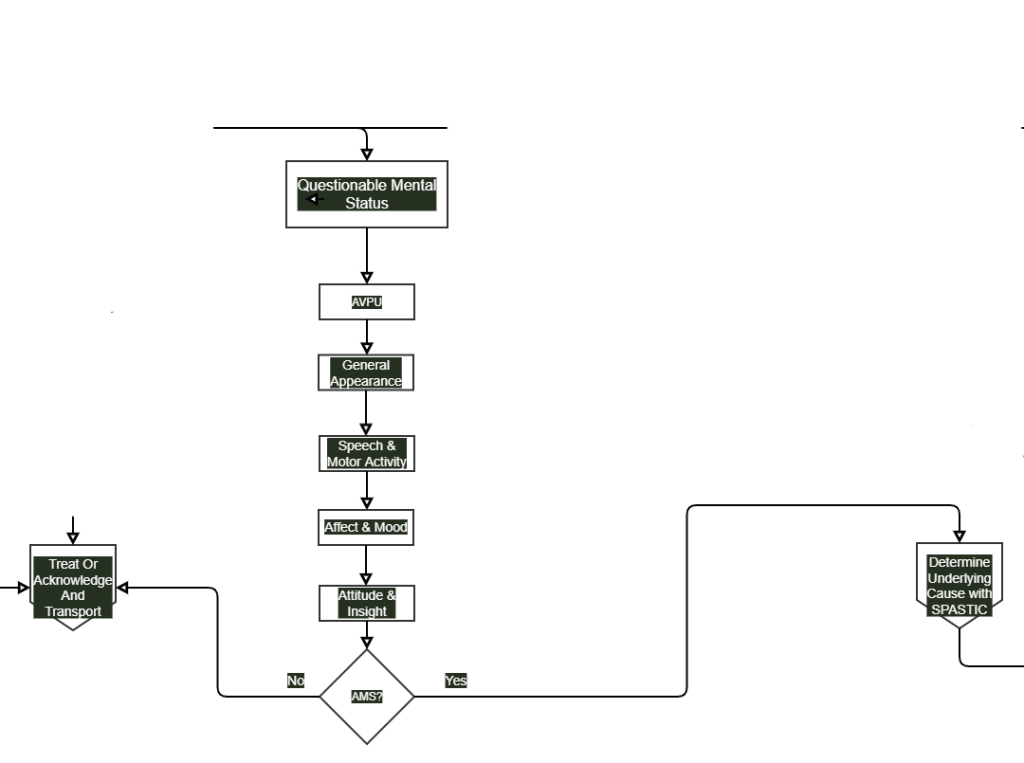

Mental Status Exam

Published (updated: ).

Level of Consciousness

Medical illness, traumatic brain injury, alcohol intoxication, drugs, and poisonings may all lead to aberrations in a patient’s neurological and physiological status in ways that cause an abnormal level of consciousness. AVPU is a straightforward scale that is useful to rapidly grade a patient’s gross level of consciousness, responsiveness, or mental status. It comes into play during pre-hospital care, emergency rooms, general hospital wards, and intensive care unit (ICU) settings.

The basis of the AVPU scale is on the following criterion:

- Alert: The patient is aware of the examiner and can respond to the environment around them independently. The patient can also follow commands, open their eyes spontaneously, and track objects.

- Verbally Responsive: The patient’s eyes do not open spontaneously. The patient’s eyes open only in response to a verbal stimulus directed toward them. The patient can react to that verbal stimulus directly and in a meaningful way.

- Painfully Responsive: The patient’s eyes do not open spontaneously. The patient will only respond to the application of painful stimuli by an examiner. The patient may move, moan, or cry out directly in response to the painful stimuli.

- Unresponsive: The patient does not respond spontaneously. The patient does not respond to verbal or painful stimuli.

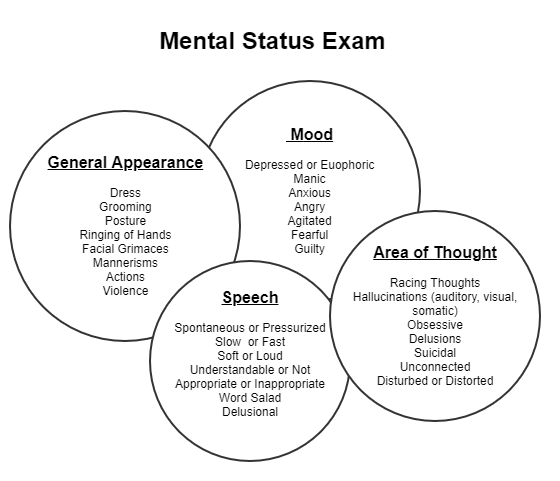

Appearance and General Behavior

These variables give the examiner an overall impression of the patient. The patient’s physical appearance (apparent vs. stated age), grooming (immaculate/unkempt), dress (subdued/riotous), posture (erect/kyphotic), and eye contact (direct/furtive) are all pertinent observations. Certain specific syndromes such as unilateral spatial neglect and the disinhibited behavior of the frontal lobe syndrome are readily appreciated through observation of behavior.

Speech and Motor Activity

Listening to spontaneous speech as the patient relates answers to open-ended questions yields much useful information. One might discern problems in output or articulation such as the hypophonia of Parkinson’s disease, the halting speech of the patient with word-finding difficulties, or the rapid and pressured speech of the manic or amphetamine-intoxicated patient. Overall motor activity should also be noted, including any tics or unusual mannerisms. Slowness and loss of spontaneity in movement may characterize a subcortical dementia or depression, while akathisia (motor restlessness) may be the harbinger of an extrapyramidal syndrome secondary to phenothiazine use.

Affect and Mood

Affect is the patient’s immediate expression of emotion; mood refers to the more sustained emotional makeup of the patient’s personality. Patients display a range of affect that may be described as broad, restricted, labile, or flat. Affect is inappropriate when there is no consonance between what the patient is experiencing or describing and the emotion he is showing at the same time (e.g., laughing when relating the recent death of a loved one). Both affect and mood can be described as dysphoric (depression, anxiety, guilt), euthymic (normal), or euphoric (implying a pathologically elevated sense of well-being).

Affect must be judged in the context of the setting and those observations that have gone before. For example, the startled-looking patient with eyes wide open and perspiration beading out on the forehead is soon recognized as someone suffering from Parkinson’s disease, when the paucity of motion and diminished eye blink are noted and the beads of perspiration turn out to be seborrhea.

Thought and Perception

The inability to process information correctly is part of the definition of psychotic thinking. How the patient perceives and responds to stimuli is therefore a critical psychiatric assessment. Does the patient harbor realistic concerns, or are these concerns elevated to the level of irrational fear? Is the patient responding in exaggerated fashion to actual events, or is there no discernible basis in reality for the patient’s beliefs or behavior?

Patients may exhibit marked tendencies toward somatization or may be troubled with intrusive thoughts and obsessive ideas. The more seriously ill patient may exhibit overtly delusional thinking (a fixed, false belief not held by his cultural peers and persisting in the face of objective contradictory evidence), hallucinations (false sensory perceptions without real stimuli), or illusions (misperceptions of real stimuli). Because patients often conceal these experiences, it is well to ask leading questions, such as, “Have you ever seen or heard things that other people could not see or hear? Have you ever seen or heard things that later turned out not to be there?” Likewise, it is necessary to interpret affirmative responses conservatively, as mistakenly hearing one’s name being called, or experiencing hypnagogic hallucinations in the peri-sleep period, is within the realm of normal experience.

Of all portions of the mental status examination, the evaluation of a potential thought disorder is one of the most difficult and requires considerable experience. The primary-care physician will frequently desire formal psychiatric consultation in patients exhibiting such disorders.

Attitude and Insight

The patient’s attitude is the emotional tone displayed toward the examiner, other individuals, or his illness. It may convey a sense of hostility, anger, helplessness, pessimism, overdramatization, self-centeredness, or passivity. Likewise, the patient’s attitude toward the illness is an important variable. Is the patient a help-rejecting complainer? Does the patient view the illness as psychiatric or nonpsychiatric? Does the patient look for improvement or is he or she resigned to suffer in silence?

Patient attitude often changes through the course of the interview, and it is important to note any such changes.

Put It All Together