Signs of Inadequate Ventilation

Published .

If we’ve said it once, we have said it a million times. People that need to be ventilated (with a bag valve mask) are, for the most part UNCONSCIOUS, or minimally not alert. The vast majority of time, a person who is just having shortness of breath will not let you bag them (try as you might). The context of this piece begins with assessing the patients level of consciousness. If the patient is alert, the patient probably does not need to be ventilated with a bag valve mask. Anything less than alert (verbally responsive, responsive to pain, or unresponsive) and the patient needs their airway evaluated by looking, listening, and feeling for breathing. After the airway has been determined to be clear, the medics must decide if the patient needs positive pressure ventilation. The simplest way to start is to assume that any patient who is not alert will need ventilation and stop when it’s obviously unnecessary. The primary survey provides useful guidance for determining if ventilation is needed for an unconscious patient (by assessing the rate, rhythm, and quality of breathing). Other clues are evaluating the unresponsive patient for abnormal work of breathing, abnormal breath sounds, decreased minute volume, chest wall pattern, or irregular respiratory pattern.

Abnormal Work Of Breathing

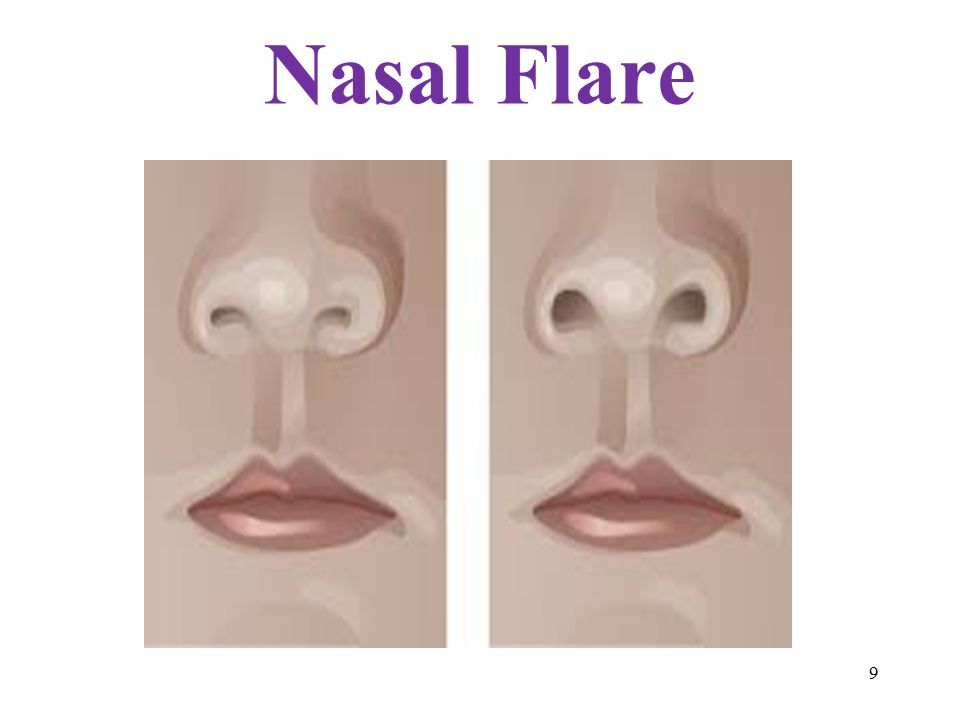

Even if the medics were unable to determine that the patient is experiencing respiratory distress from the rapid respiratory distress, they could find outward signs of respiratory distress which need no counting of respirations. Nasals flaring is seen when the patient flexes the muscles in their nose to make their nostrils larger in an attempt to breathe in more air volume. An adult could be breathing more with their abdominal muscles than their chest wall. Retractions are seen when the patient (primarily from bronchoconstriction) has to work extra hard to exhale. The added effort creates a vacuum that sucks the skin to the bones. Retraction can be easily be seen in the chest and neck. Nearly every case where a patient requires ventilation will be met with a patient presenting with diaphoresis (profuse sweating).

Abnormal Breath Sounds

Listening to breath sounds is a classic EMT skill. Auscultation of breath sounds can help medics determine the underlying cause of respiratory distress and provide appropriate treatment. Listening to breath sounds would be more useful if the patient was only experiencing shortness of breath than they would if medics were considering whether or not to ventilate their patient. Nonetheless, the sounds they could expect to hear are:

- Stridor – high pitched sound coming out of the mouth primarily upon inspiration. This indicates trauma, infection, or burns to the oropharynx.

- Wheezing – auscultation of the lung fields revealing the sound of bronchoconstriction is caused by asthma, COPD, and anaphylaxis.

- Crackles – auscultation of the lung fields revealing fluids in the lungs. Fluid in the lungs can be caused by pneumonia and congestive heart failure.

- Silent Chest – auscultation of the lung fields reveal no sounds despite evidence that the patient is breathing. This finding is associated with a severe asthma attack being sustained by a patient who has survived multiple life threatening asthma attacks in the past.

- Breath sounds are unequal – auscultation of the lung fields reveal one lung is inflating and the other is not. This finding could indicate pulmonary contusion or pneumothorax from trauma. More likely, the finding is a lung infection (probably pneumonia).

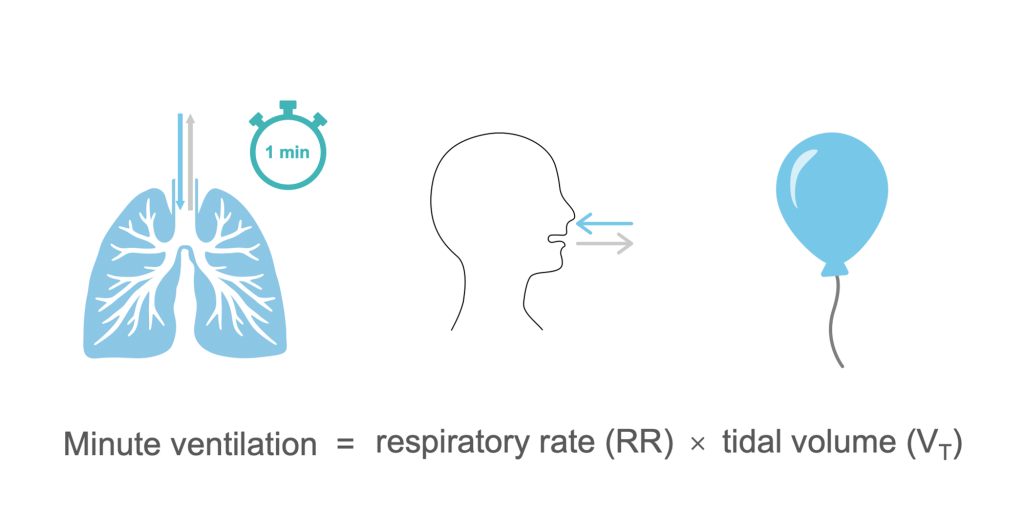

Decreased Minute Volume

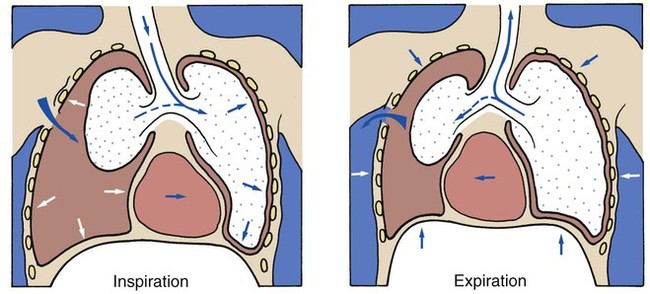

Sometimes it is hard for medics to rationalize ventilating a patient who is actually breathing. It seems counter intuitive to ventilate a patient who is breathing, however consider the plight of a patient who is only breathing 4 times a minute. If the normal respiratory cycle moves 500 ml of air and the normal respiration rate is 12 times a minute, the patient should be moving about 6000 ml of air a minute. These terms are typically expressed as respiratory volumes. 500 ml being tidal volume (the amount of air moved with each breath), and minute volume being the 6000 ml (500 ml x 12 breaths per minute). 6000 ml of air movement a minute is a normal amount, but what about the patient only breathing 4 times a minute? The patient is probably moving only 2000 ml of air a minute with their respirations. Obviously, a patient who is only breathing 4 times a minute is not going to be conscious (which is the first clue that the patient needs ventilation).

Chest Wall Movement or Damage

Medics are trained to look at the chest for certain injuries that would cause the patient to struggle breathing. When these injuries are found, medics must immediately treat them:

- Flail chest – discovered when the patient has paradoxical respirations (each side of the lung moving in opposition to each other as a result of 2 or more ribs broken in 2 or more places.

- Penetrations – If a penetrating wound to the chest penetrates a lung, the negative pressure from normal respiration will pull air into the the patient’s chest (but not into the lungs). This infusion of air into the chest will create a pocket of air that may eventually grow until it applies pressure to the unaffected side.

Irregular Respiratory Pattern

The unresponsive patient may exhibit an irregular respiratory pattern based on a number of underlying causes:

- Head Trauma – Patients with injuries to their brainstem or pons may breathe irregularly, rapidly, or very slowly depending upon the injury. Patients with increased intracranial pressure respiratory rate could decrease to 2 or 3 breaths per minute.

- Stroke – Stroke patients, primarily patients decompensating from a cerebrovascular bleeding may also experience increased intracranial pressure that would result in a decrease in respiratory rate.

- Metabolic – Various metabolic conditions could result in aberrant respiratory rate or rhythm. A condition that all medics should be aware of is Kussmaul’s respirations. Kussmaul’s respirations are very fast (like 40 breaths a minute). These patients breathe this way in order to blow off as much carbon dioxide as possible in an attempt to regulate their pH.

- Toxic – Various toxins can affect respiratory rate and rhythm. The best example is opiates. Opiates are analgesics (pain relievers) derived from the opium plant. These drugs have a powerful affect on the central nervous system. An overdose of opiates typically results in a decreased respiratory rate.

- Hyperventilation – For a variety of reasons, patients will hyperventilate