SIDS & ALTE

Published .

Sometimes baby’s just die in their sleep

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) is the sudden, unexplained death of a baby younger than 1 year of age that doesn’t have a known cause even after a complete investigation. This investigation includes performing a complete autopsy, examining the death scene, and reviewing the clinical history.

When a baby dies, health care providers, law enforcement personnel, and communities try to find out why. They ask questions, examine the baby, gather information, and run tests. If they can’t find a cause for the death, and if the baby was younger than 1 year old, the medical examiner or coroner will call the death SIDS.

If there is still some uncertainty as to the cause after it is determined to be fully unexplained, then the medical examiner or corner might leave the cause of death as “unknown”.

Facts About SIDS

- SIDS is a sudden and silent medical disorder that can happen to an infant who seems healthy.

- SIDS is sometimes called “crib death” or “cot death” because it is associated with the time when the baby is sleeping. Cribs themselves don’t cause SIDS, but the baby’s sleep environment can influence sleep-related causes of death.

- SIDS is the leading cause of death among babies between 1 month and 1 year of age.

- About 1,360 babies died of SIDS in 2017, the last year for which such statistics are available.

- Most SIDS deaths happen in babies between 1 month and 4 months of age, and the majority (90%) of SIDS deaths happen before a baby reaches 6 months of age. However, SIDS deaths can happen anytime during a baby’s first year.

- Slightly more boys die of SIDS than girls.

- In the past, the number of SIDS deaths seemed to increase during the colder months of the year. But today, the numbers are more evenly spread throughout the year.

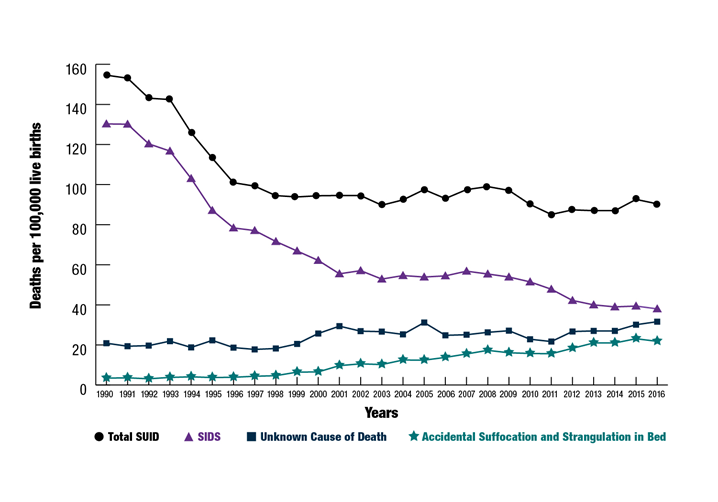

- SIDS rates for the United States have dropped steadily since 1994 in all racial and ethnic groups. Thousands of infant lives have been saved, but some ethnic groups are still at higher risk for SIDS.

Damned if you do, damned if you don’t

If the patient is obviously dead, the medics should turn their attention to the family. Losing a child is the worst thing a family can endure. To say that that not working the patient puts the EMS crew in an awkward situation is an understatement. Some medics will work the patient completely in vain as a way to escape the awkward situation. If the medics choose to not work the patient, they should observe and document the following:

- Motionless appearance

- Signs of obvious death such as rigor mortis (stiffness in extremities) and lividity (redness from blood pooling)

- Absence of heart tones – Listen for heart tones with a stethoscope

- Absence of breath sounds

- History to include the last time the patient was seen and if there had been any medical problems

If the medics have opted to not initiate CPR, they should follow local procedures for managing an out of hospital death. Typically, the police will have an interest in the matter as the death could be a homicide or require further assessment to determine if the law has been violated. Sometimes, the ambulance service will transport the patient to the hospital to be pronounced dead by a doctor (EMS only chose to not initiate CPR, only a doctor or coroner can pronounce death). In some areas, the coroner will be summoned to the scene and will arrange to have the patient transported from the scene

If there is any confusion on whether the patient is obviously dead or when the last time the patient was seen, the the medics should initiate CPR and transport to the hospital.

Apparent Life Threatening Event (ALTE) is a SIDS near miss incident

An apparent life-threatening event (ALTE) is defined as the combination of clinical presentations such as apnea, marked change in skin and muscle tone, gagging, or choking. It is a frightening event, and it predominantly occurs during infancy at a mean age of 1–3 months. The causes of ALTE are categorized into problems that are:

- gastrointestinal (50%)

- neurological (30%)

- respiratory (20%)

- cardiovascular (5%)

- metabolic and endocrine (2%–5%)

- or others such as child abuse.

Up to 50% of ALTEs are idiopathic, where the cause cannot be diagnosed. Infants with an ALTE are often asymptomatic at hospital and there is no standard workup protocol for ALTE. Therefore, a detailed initial history and physical examination are important to determine the extent of the medical evaluation and treatment. Regardless of the cause of an ALTE, all infants with an ALTE should require hospitalization and continuous cardiorespiratory monitoring and evaluation for at least 24 hours. The natural course of ALTEs has seemed benign, and the outcome is generally associated with the affected infants’ underlying disease. In conclusion, systemic diagnostic evaluation and adequate treatment increases the survival and quality of life for most affected infants.