How To Assess Pediatric Patients

Published (updated: ).

Assess from a distance

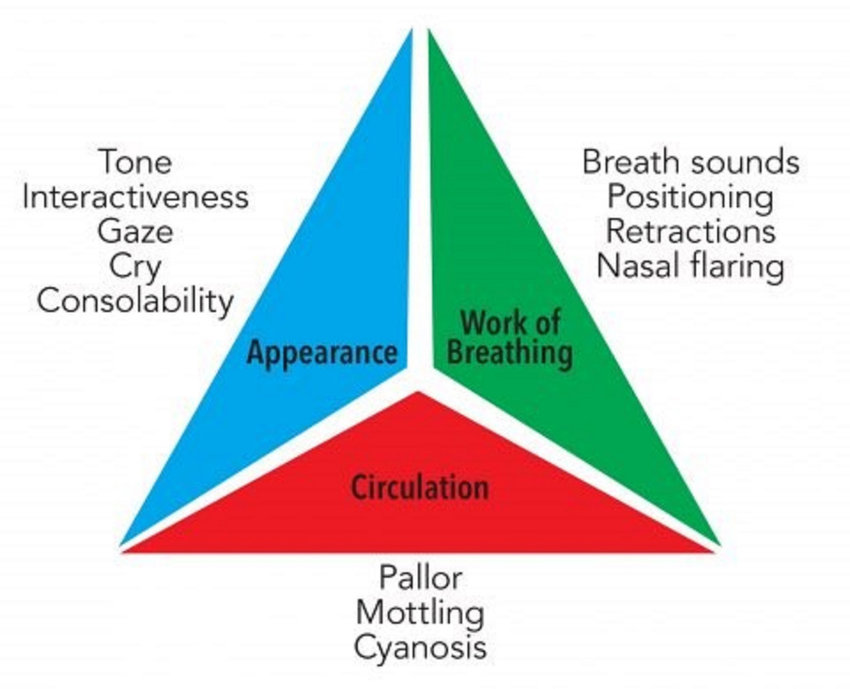

When infants and children are sick, they look sick. The same can’t always be said for adults. A useful triage tool to use when assessing an infant or child is the pediatric assessment triangle. The pediatric assessment triangle will allow the medics to perform a quick but limited assessment of the patient. Given that toddlers and older children are apt to possess much stranger anxiety, being able to assess from a distance can be very useful.

Appearance

- Muscle tone – Look at the infant or toddlers face, neck, arms, and legs. Do they appear to be flaccid or deflated? If so, this means the patient has poor muscle tone.

- Interactiveness – Does the patient interact with rescuers, siblings, or family members? Observing an infant or child that just seems to be in their own little world is not a good sign

- Consolability – If the infant or child is upset, but can be consoled (or calmed) by the parent or guardian, the patient is said to be consolable. When a pediatric patient is experiencing serious distress, they will be inconsolable.

- Eye contact – Eye contact speaks to the interactiveness of the patient. If the patient is unable to make eye contact, the patient could be having serious problems.

- Speech or cry – On the flip side of consolability is a complete lack of speech or cry. If the patient is completely silent. Something is very wrong with the patient.

Breathing

- Assess the patient’s work of breathing – When a patient is experiencing difficulty breathing, they will look like they are working to take a breath. Other signs that indicate increased work of breathing are abnormal airway noises (wheezing, stridor, or grunting).

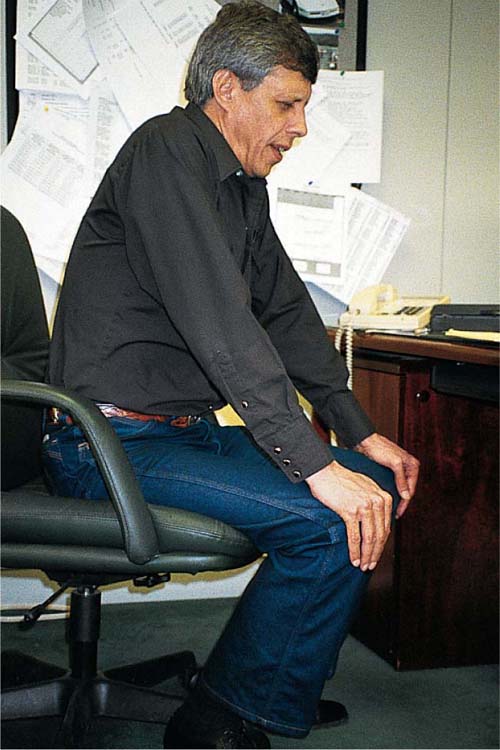

- Abnormal positioning – When patients are experiencing difficulty breathing they may position their body in a way that makes it easier to breathe. The most obvious example is the tripod position.

- Accessory muscle usage – When patients are experiencing difficulty breathing their body will make changes to increase the volume of inspired air. The skin of the thorax will be pulled tightly against the ribs, revealing the work of accessory muscles. The skin is pulled back due to the vacuum created by the effort of the lungs and accessory muscles to pull in more air volume. Nasal flaring is also common. The nares will dilate with each breath with the intent of bringing in more air volume.

Circulation

From a distance, the medics can look at the patient’s skin to see if it is pale, mottled (blotchy), or cyanotic (blue). This observation that can be made from a distance can help the medics predict if the patient is experiencing shock or hypoxia.

Utilize the parent or guardian to help the infant or child to become more comfortable with the physical exam

When assessing and treating infants and children, the medics may need to enlist the help of the parent or guardian. The infant or child in distress doesn’t understand that the medics are there to help. The assessment and treatment may involve increasing the anxiety of the patient, having some extra hands can be useful.

Communicating with scared, concerned parents is important when caring for the ill infant or child

The medic needs to know what to do and how it needs to be done. Bystanders and fellow responders should all be given something to do, no task is too small. Enlisting the help of those on scene is an excellent way to manage any call, but especially a call involving an infant or child. Providing a little direction to family and other responders who arrive on scene is an excellent way to allow them to participate in the outcome of the situation.

Continue assessment until care is transferred

Pediatric patients have the capacity to suddenly decompensate without warning. The best strategy is to continually assess your pediatric patient, always looking for something that was missed. Medics should be on the hunt for changes to the patients initial condition. Maybe the patient is starting to experience difficulty breathing or shock. Even if the medics have already performed a primary survey and focused history and physical exam on the patient, they should repeat these assessments all the way to hospital.

Have reasonable expectations of patient behavior based on life span development

- Newborns- They should always be crying and moving their arms and legs. They will go to anyone. Neonates tend to be hungry; allowing them to breastfeed before transport is the only way to keep them happy.

- Infants – Infants tend to be fairly agreeable with medical assessment and treatment so long as the mother or guardian is within arms reach. When the mother or guardian is not around, the infant will probably experience separation anxiety.

- Toddlers – Toddlers don’t like strangers and frequently have poor interactions with medics. This is the patient where being able to perform some type of assessment from across the room would come in handy. Other techniques include the sneak attack. If you have the mother hold the toddler, the medics can perform a fairly adequate assessment from behind the patient’s back.

- Older children – Older children can be reasoned with and can be very helpful patients, however there is an Achilles heel; they are terrified of permanent disfiguring injuries. Bandaging wounds and worrying about the modesty of the older child goes a long way. Start with trying to treat the older child like an adult, more times than not they will try to act like an adult.

- Possibility for regression to an earlier age – Pain and stress affect all people differently. It is not abnormal for a 6 year old to act like a toddler if he or she is in pain under stress. Other children may actually act older than their age.

Medics need to utilize different assessment parameters

Unless the medics have electronic non invasive blood pressure cuffs to assess a blood pressure, taking a blood pressure on an infant or toddler can be challenging. Most hospitals are okay with assessing for the presence distal circulation (brachial pulse) in lieu of a blood pressure. The capillary refill time is an excellent early indication that the infant or toddler is compensating for shock (early warning is great because they compensate so fast). To assess capillary refill time (CRT), simply apply pressure a fingernail the count how long it takes for the fingernail to return to it’s original color. A delayed CRT is 3 seconds or greater and means that the patient is compensating for shock. The CRT may be the only indication that medics could find that could lead to shock. When the patient decompensates for shock, the decompensation will be quick and without warning. Shock lurks in the dark waiting to take the life of an infant or toddler.

Ensure the ambulance has pediatric equipment on board before going into service

Before the ambulance even gets on the road, a thorough inventory of the contents of the ambulance is conducted. The medics should ensure the ambulance has equipment (like pulse oximetry probes and infant sized blood pressure cuffs) for infants and toddlers. Having the proper sized equipment for pediatric patients of all ages is important if the ambulance crew expects to be able to use it on a call.