Injuries To The Spine

Published (updated: ).

The problem with fractures to the spinal column

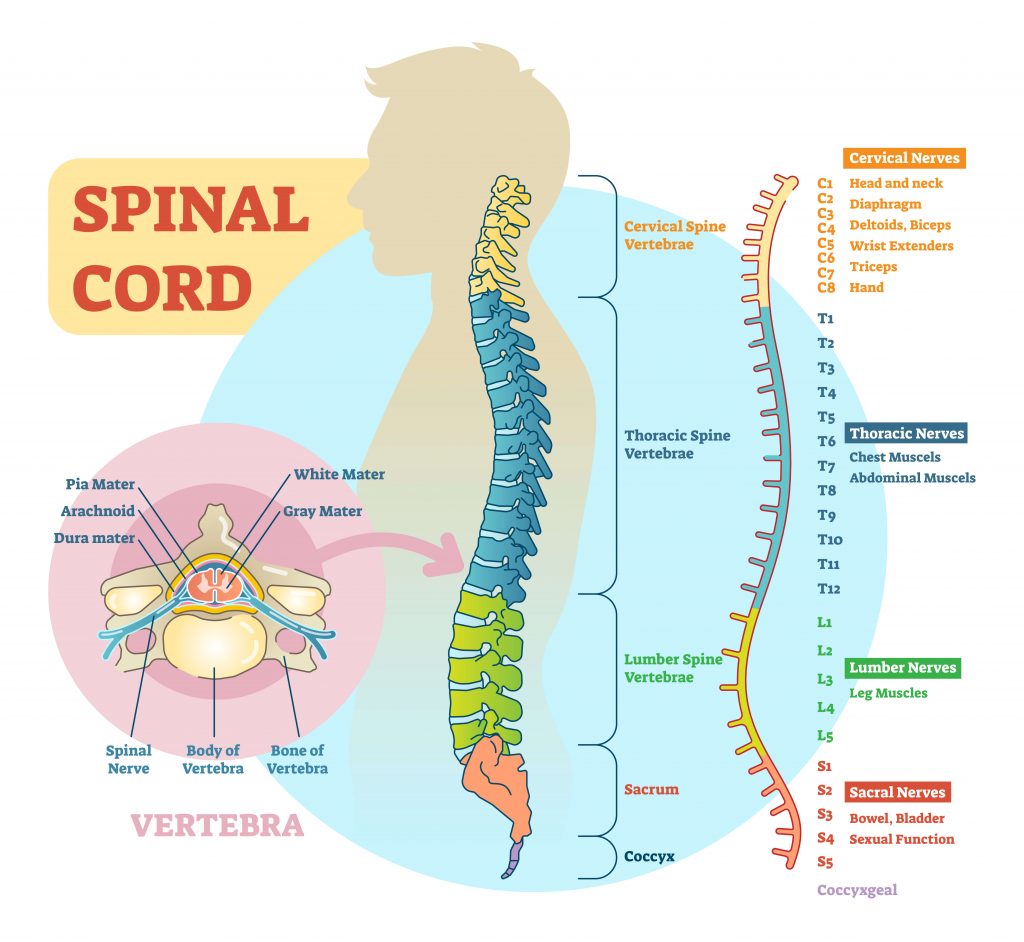

The spinal cord is an extension of the brain and forms the lower half of the central nervous system. An injury to the spinal cord offers the same level of catastrophic outcome as a head injury. The spinal cord is made of the same materials as the brain (cerebrospinal fluid, gray and white matter). Like the brain, injuries to the spinal cord can be difficult or impossible to recover from. The spinal cord travels from the brainstem and down the back through a canal made of interconnected bones called vertebrae. The vertebrae are arranged on top of each other and linked together like a chain (commonly referred to as the vertebral column). The vertebrae are very strong and flexible; which provides excellent protection to the spinal cord.

What would happen if one of these vertebrae were broken? There is a good chance that the broken bone would sever the spinal cord. When the spinal cord is damaged, permanent neurological deficit is very likely. So how are the medics to know the patient has a spinal cord injury? It’s not like they can see the spinal cord is broken with their own eyes. The tip off is the mechanism of injury. Understanding the mechanism of injury can help EMS predict the possibility of injuries to the patients spinal column.

Mechanism of injury that suggest injuries to the spinal column

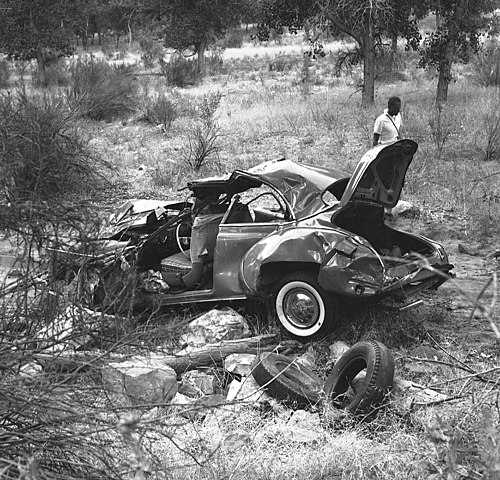

- Motor vehicle crashes

- Pedestrian vehicle collisions

- Falls

- Blunt trauma

- Penetrating trauma to the head, neck, or torso

- Motorcycle crashes

- Hanging

- Springboard or platform diving accidents

- Unresponsive trauma patients

Spinal cord injury symptoms

Aside from just assuming the patient has a spinal cord injury based on the mechanism of injury, there are symptoms. The symptoms of a spinal cord injury are based on the location of the trauma (cervical vs lumbar). The patient may experience tenderness (pain upon palpation). If the patient is experiencing pain with movement, do not try to get the patient to duplicate the movement in an attempt to find the location of the pain. Any movement of the spine can shift a potentially broken vertebrae into the spinal cord, possibly resulting in permanent injury. The patient may experience numbness or tingling in the extremities below the injury site. Very often the patient becomes incontinent to bowel or bladder. Patients with cervical spine (the neck) fractures often experience nuchal rigidity (inability to turn the neck to one side or the other). If the patient is unresponsive, the patient may stop breathing if the phrenic nerve has been affected.

Just because patient is able to ambulate and move their arms doesn’t mean they have not sustained a spinal cord injury. It may be necessary to ask additional questions about the mechanism of injury:

- Does your neck or back hurt?

- What happened?

- Where does it hurt?

- Can you move your hands and feet?

- Can you feel me touching your fingers?

- Can you feel me touching your toes?

Patient management

The first clue that the patient has sustained a spinal cord injury is the mechanism of injury. If the mechanism of injury is significant enough, pull the equipment required to immobilize the patient off the ambulance and have it ready when you meet the patient. Since the medics have a clue about the presence of a spinal cord injury, one of the earliest priorities is spinal immobilization. Spinal immobilization assumes the patient has a broken cervical vertebrae.

- The cervical spine is manually stabilized in the neutral and inline position. This means that the neck is neither flexed or extended. If the neck is in a position other than neutral, the medics must move the patient’s head in order for the neck to be in a neutral and inline position. The medic stabilizing the cervical spine will remain holding the patient’s head in this position until the head has been secured to the backboard.

- The medics need to determine if the patient has any peripheral neurological deficits. This is accomplished by assessing the distal pulse and asking the patient to move their hands. Next, the medics touch the patient’s hands to see if the patient can feel the touch. This assessment is referred to as pulse, motor, sensory or PMS.

- With other rescuers, the patient will be log rolled. After the patient is on their side, a long backboard will be slid underneath their back.

- The patient will be log rolled onto the long backboard.

- The patients torso (body and legs) will be secured to the backboard first. The reason the torso is first is to be ready in case the patient vomits. If the patient vomits, the patient will need to be log rolled again to clear the airway. It would be much easier to log roll the patient if the torso was secured to the backboard.

- The patient’s head is secured with a cervical collar and blocks. The blocks prevent the patient from moving their head to the right or left while the cervical collar ensures the patient is unable to extend or flex their neck.

- PMS is assessed in all four extremities. Any deficits are documented.