CPR: Knowing When To Quit

Published (updated: ).

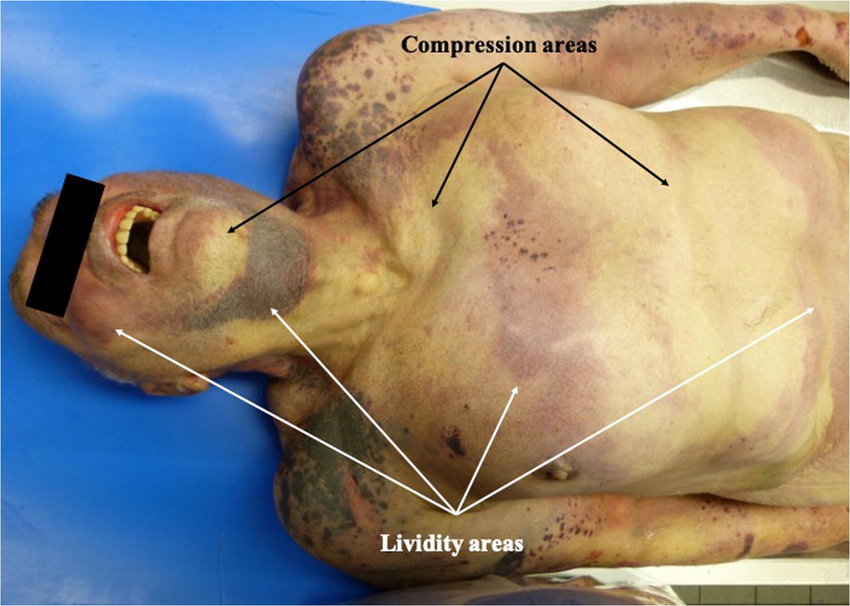

Ambulance services shouldn’t be expected to perform CPR on patients who are obviously deceased

Sometimes, the ambulance crew is summoned to the scene of a person unconscious, only to discover that the patient is obviously dead. When a patient is obviously dead, there is no reason to begin resuscitative efforts. Sometimes, it’s obvious that the patient is deceased (like decapitation, massive bleeding, etc.). Medics can’t legally declare a patient is dead, but they certainly can determine if a patient is a suitable candidate for resuscitation. Once the determination has been made to not work the patient, the ambulance crew should follow the local guidelines (which could be anything from requesting the police department manage the body, wait for the duly elected coroner, or transport the patient by ambulance to the ER to be pronounced dead by a physician. Sometimes, the fact that a patient is dead is obvious to the medics but not to anyone else. If the medics decide to not resuscitate the patient, a perimortem examination should be completed and documented:

- No respirations as determined by opening the airway using the head tilt-chin lift maneuver (or jaw thrust if a cervical spine injury is suspected) and observing for the rise and fall of the chest wall while listening and feeling for breath for at least 30 seconds

- No pulse as determined by palpation of the carotid or auscultation of the apical pulse (listening for heartbeats with a stethoscope) for at least 30 seconds

- Dilated bilateral pupils (if assessable) that are unresponsive to bright light

- Dependent lividity (redness)

- If rigor mortis is present, as determined by the presence of hardening of the muscles or rigidity of the jaw, shoulders, elbows or knees, then a finding of dependent lividity is not required.