Evidence Based Decision Making

Published .

Traditional medical practice is based on medical knowledge, intuition (the ability to understand something completely without the need to think about it), and judgment (the ability to make considered decisions or come to sensible conclusions). High quality patient care should focus on procedures that have been proven useful in improving patient outcomes.

Emergency Medical Services suffer from a distinct lack of research making it difficult to determine if various interventions actually work in a given situation. The data gap is decreasing as EMS struggles to become more and more integrated with the NEMSIS database.

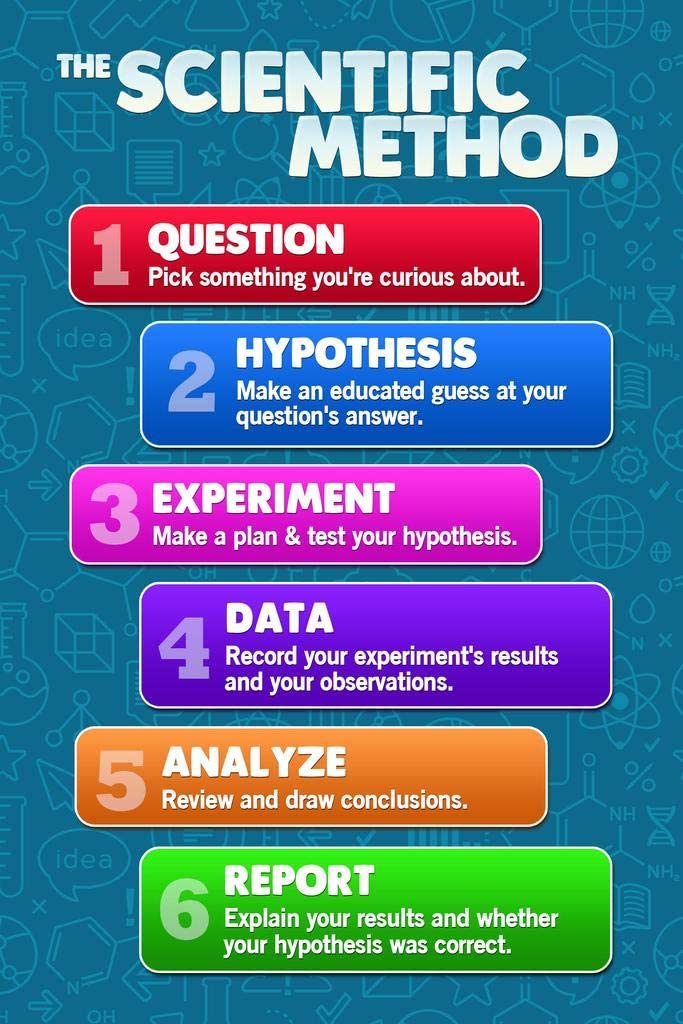

The most acceptable approach is an evidence based decision making technique (based on the scientific method). The first step is to question treatments that are appropriate (no need to question treatments that are inappropriate). The clinician then searches medical literature and looks for the possibility that someone else already asked the question. If evidence is found to support or not support the appropriateness of a treatment, the clinician must then evaluate the evidence for validity and reliability. Based on the evidence, the treatment will continue or a new therapy will be adopted.

Let’s take a look at one of these research articles.

Euthanasia and assisted suicide of persons with psychiatric disorders: the challenge of personality disorders

Marie E Nicolini 1 2, John R Peteet 3, G Kevin Donovan 4, Scott Y H Kim 2Affiliations expand

Abstract

Background: Euthanasia or assisted suicide (EAS) for psychiatric disorders, legal in some countries, remains controversial. Personality disorders are common in psychiatric EAS. They often cause a sense of irremediable suffering and engender complex patient-clinician interactions, both of which could complicate EAS evaluations.

Methods: We conducted a directed-content analysis of all psychiatric EAS cases involving personality and related disorders published by the Dutch regional euthanasia review committees (N = 74, from 2011 to October 2017).

Results: Most patients were women (76%, n = 52), often with long, complex clinical histories: 62% had physical comorbidities, 97% had at least one, and 70% had two or more psychiatric comorbidities. They often had a history of suicide attempts (47%), self-harming behavior (27%), and trauma (36%). In 46%, a previous EAS request had been refused. Past psychiatric treatments varied: e.g. hospitalization and psychotherapy were not tried in 27% and 28%, respectively. In 50%, the physician managing their EAS were new to them, a third (36%) did not have a treating psychiatrist at the time of EAS request, and most physicians performing EAS were non-psychiatrists (70%) relying on cross-sectional psychiatric evaluations focusing on EAS eligibility, not treatment. Physicians evaluating such patients appear to be especially emotionally affected compared with when personality disorders are not present.

Conclusions: The EAS evaluation of persons with personality disorders may be challenging and emotionally complex for their evaluators who are often non-psychiatrists. These factors could influence the interpretation of EAS requirements of irremediability, raising issues that merit further discussion and research.

Keywords: Assisted suicide; clinical ethics; euthanasia; personality disorders; psychiatry.